If you are an artist with a big museum show, this must be a time of mixed emotions. This is your moment—one that might not be repeated for a generation, if ever! And yet many of the mechanisms that make an exhibition agenda-setting—even life-changing, for artists—are currently disabled by the Covid-19 crisis.

Exhibitions need a perfect storm of events to capture the zeitgeist. The art needs to be great, of course; the media interviews intriguing; reviews ecstatic; the private view buzzing; other art-world events in the same week alive with artists, critics, curators, collectors and dealers sharing their excitement; the first public days thronging and noisy, the Tube/subway posters bold and alluring—all adding up to irrepressible word-of-mouth and social media fizz.

But much of this is impossible today. A fifth of visitors can visit museum shows because of social distancing, there is no big private view, and fewer people absorb those posters on relatively quiet undergrounds. Of course, there will be enthusiastic exchanges on WhatsApp groups, and acclaim on Twitter and Instagram, but that magical moment when the perfect storm makes landfall relies on the real, social world and the digital realm acting in tandem.

For our exhibition-making institutions to be denied these possibilities—like, in London, the troubled Hayward Gallery (part of the Southbank Centre) and Royal Academy (RA), and the Whitechapel Gallery—especially those with little or no public funding, this could be disastrous. Shows’ momentum is their lifeblood, bringing the crowds to spend money on tickets but also in their shops and cafés. Now their funding models are unable to cope with shocks.

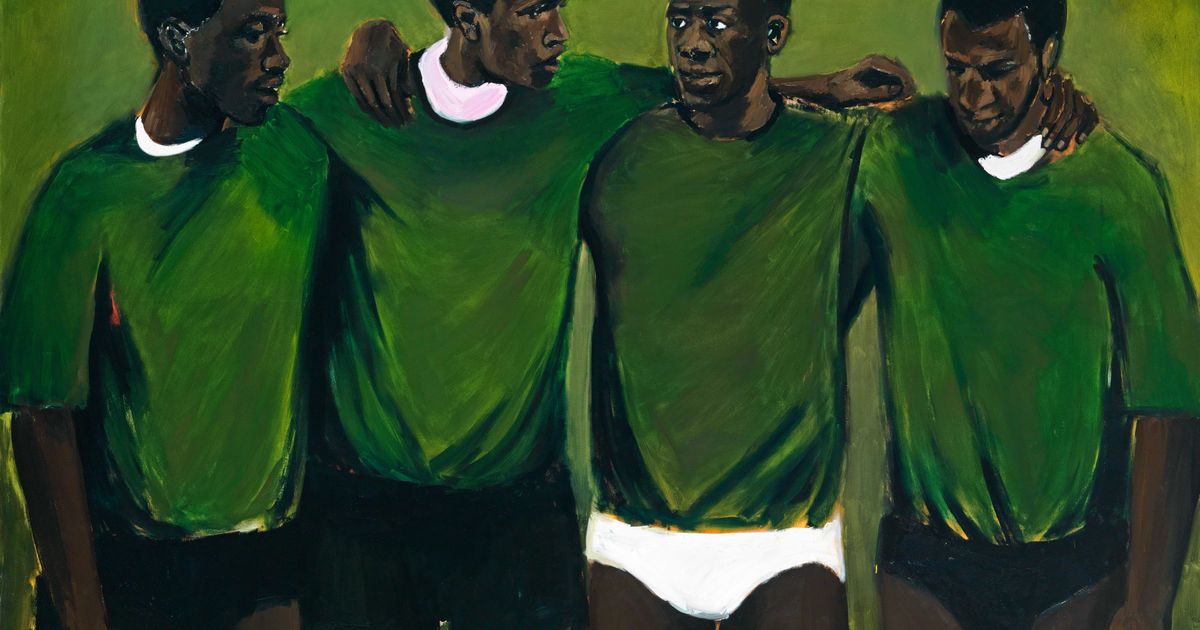

Compared with those at the Tate, Southbank Centre, RA and elsewhere who are losing their jobs—many of them artists, working at the institutions by day and in their studios by night and at weekends—the artists with big gallery shows, like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at Tate Britain or Zanele Muholi at Tate Modern, both opening next month—are relatively lucky, of course. But still, their big moments are somewhat blighted.

An exhibition’s true impact, its legacy, is often defined by other artists, when a critical mass of fellow practitioners absorb the show into their thoughts and actions.

Perhaps the most famous in post-war Britain—a truly epochal moment—was the Jackson Pollock exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1958. “The Pollock show was the show that knocked my socks off,” says the artist Allen Jones, who was then a student at Hornsey College of Art. “I remember going with [the artist] Ken Kiff… We were astonished, and we felt that we had a case for suing the art school, because we were in total ignorance of what was happening in the contemporary art world.”

Anyone who has been to art school knows that moment when a show hits home: visual language suddenly shifts to absorb the excitement, almost as if there had been a formal exercise. Of course, this can still happen for Yiadom-Boakye and Muholi, even in the current circumstances. But with no group student visits, no art-world private view, and limits on public access, the buzz has potentially been short-circuited.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/covid-19-the-biggest-buzzkill