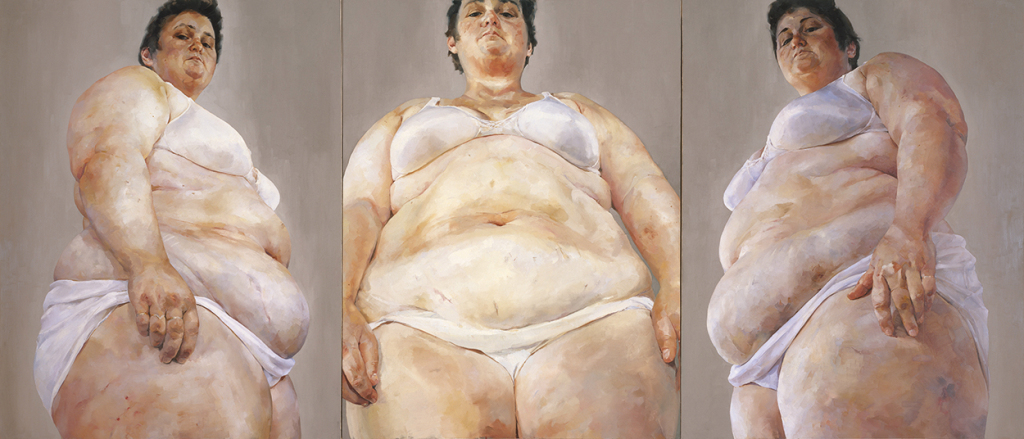

Jenny Saville, Strategy, 1994, oil on canvas, in three panels, 108 x 250½ inches. Photo Prudence Cuming/Courtesy Gagosian/©Jenny Saville

Jenny Saville, Strategy, 1994, oil on canvas, in three panels, 108 x 250½ inches. Photo Prudence Cuming/Courtesy Gagosian/©Jenny Saville  Roxane Gay Illustration by Scott Chambers

Roxane Gay Illustration by Scott Chambers  Jenny Saville Illustration by Scott Chambers

Jenny Saville Illustration by Scott Chambers

Roxane Gay, a prominent author, has been confronting the pervasive bias against fat women. In her 2017 book Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, Gay relates stories about the rudeness she often encounters when seated next to strangers on a plane. She considers fatphobia a feminist issue, writing, “As a woman, as a fat woman, I am not supposed to take up space. And yet, as a feminist, I am encouraged to believe I can take up space.” British artist Jenny Saville’s powerful works celebrating the beauty of fat women are among her most well-known; her trailblazing feminist paintings helped chart a path for women painters who talk back to the female nudes that dominate art history. This involves challenging the standards of beauty codified in images, be they art or ads, to which women are often pressured to conform. While figures who are plump by today’s standards have featured prominently in classic paintings by Titian, Rubens, and others, these women are what Gay calls “Lane Bryant fat,” a term she coined to refer to people who shop at the plus-size retailer that sells clothing generally up to size 28. For Gay, the cutoff at that size speaks to the degree of fatness that society is willing to accommodate, and to the limited options that people size 29 and up often have. Gay, who is based in New York and Los Angeles, chatted over Zoom with Saville, who is based in Oxford, on the subject of fatness and feminism, as well as their shared commitment to nurturing a younger generation of women writers and artists.

ROXANE GAY: I first saw your work at the Broad Museum. I was just walking around, then I looked up, and I saw this huge triptych [Strategy, 1994] that shows a fat woman—a woman with her breasts sagging, with stomach rolls. It was the first time I’d ever seen a body that looks like mine in an artwork, and it was incredible. I became obsessed. In most art, when a woman is fat, she’s not actually that fat—she’s just sort of plump. She doesn’t have any rolls or wrinkles or stretch marks. And here I saw fat bodies, unadorned and unapologetic. It was really surprising. We know that representation matters, but when you see the kind of representation you didn’t even know you wanted, it can be really meaningful.

SAVILLE: I made that picture a long time ago. The model is a friend of mine. I just found her body so unbelievably powerful. I was thinking about this idea that you’re the only one who can never see your own body in its entirety—you’re condemned to images of it. So I wanted to construct paintings that were about seeing bodies from many different angles all at the same time—like when you go into one of those changing rooms with multiple mirrors, and as you turn around, you can see bits of yourself that you didn’t even know existed. The triptych received a lot of negative press when I first showed it in 1994 at the Saatchi Gallery in London. You wouldn’t believe the language: it was about obesity; about how gross this person was. And I just thought, “this is my friend!” I had asked her to model because I thought she was beautiful! I had no idea I was making this charged image. But I’ve been very moved by the number of people who have written to me, saying that my painting was the first time they’d seen themselves on canvas. Ultimately, I think my friend found the experience empowering. Now she’s 53, and she loves that people like to see her in paintings. She feels proud to have shown her body in that way. Working with models is really a collaboration, and it’s an honor when they trust me.

GAY: It must take real courage to model, because so many people are going to judge your body in so many different ways. And also, because people love to have opinions about fatness, and to make assumptions about your health.

SAVILLE: For me, the painting wasn’t just about her size—it was just about how beautiful she looked. Some people ask me, how can you think somebody like that is beautiful? But honestly, I just do. After witnessing all these strong reactions to the triptych, I became even more interested in bodies that some might see as “misbehaving,” whether through violence or surgery, or bodies that don’t have a fixed gender—that became a decade’s worth of my work, and in some ways, I’m still exploring that theme.

GAY: I edited a collection of essays by myself and others called Unruly Bodies [for Gay Mag in 2018]. I think the bodies that challenge our cultural norms are always going to interest me.

SAVILLE: I didn’t realize this at the time, but misbehaving bodies are really a feminist issue. Also, making something visible and giving it cultural value is so important. During my exhibition in 2018 at Gagosian New York, I walked in with my son and we saw about twenty-five young women sitting on the floor, drawing from my paintings. It moved me so deeply. When I was younger, there just weren’t many shows by women artists, never mind paintings of different types of bodies.What are you writing now?

GAY: I’m writing two books. One is a book of writing advice called How to Be Heard, which features not only practical writing advice, but tips on how to write toward social justice, create change, and try to reach people who seem unreachable when it comes to their sociopolitical opinions. I’m also writing a young adult novel called The Year I Learned Everything, a coming-of-age story about a biracial girl in a small town in Illinois. What about you? What are you working on right now?

Saville: Virtual, 2020, oil on canvas, 78¾ by 63 inches. Courtesy Gagosian/©Jenny Saville

Saville: Virtual, 2020, oil on canvas, 78¾ by 63 inches. Courtesy Gagosian/©Jenny Saville

SAVILLE: I just showed about half the works from my “Elpis” series at Gagosian in New York, and I’m finishing the other ones now. When I went to Moscow two years ago, I saw so many amazing women—like this waitress who had an incredible face. Eventually, I started asking people if they’d model for me, and rented a studio there. The series is based on the Russian female poet Anna Akhmatova, who wrote the bulk of her work in the ’30s and ’40s, under Stalin’s rule. Her husband was executed by the Soviet secret police, and her son was imprisoned. Every day, for seventeen months, she went to the prison where he was kept and saw all these other women who were walking around trying to find information about their loved ones. She couldn’t write anything critical of the government—had the work been found, she would have been arrested or executed—so instead, she whispered the poem she wanted to write into these other women’s ears. Between 1935 and 1961, she wrote Requiem, an elegy about her experience of waiting all those months to write the words down on a piece of paper. It wasn’t published until 1987. Reading about Akhmatova, I learned about all these amazing twentieth-century women writers in Moscow, while I was there photographing those Russian subjects for the paintings [a series of boldly colored portraits of various creative women working today].

GAY: Hearing about the conditions under which some people create art is truly eye opening. It always makes me realize that, as underappreciated as the arts may be in the Western world, we at least have the freedom to make it.

SAVILLE: And also, we think of poetry as kind of quaint and gentle, not as something that’s threatening to the government. In 2019 my work was censored in China, which I couldn’t believe. All my life people have told me that I was a traditionalist because I paint in oil and because I paint figures. But in China, they actually wouldn’t publish my paintings. A young artist there modeled for me, and I told her I’d send her a book of my work, but she asked me not to because she didn’t want to get in trouble.

GAY: How do you feel when your work is censored?

SAVILLE: It definitely makes me reflect on how important artistic freedom is—not just having it, but exercising it. Had I been born fifty years earlier, I probably never would have been taken seriously as a woman artist. No gallery would have signed me on. So I want to take advantage of the moment I live in.

GAY: Absolutely. As a Black woman and a queer woman, I know that representation matters. Unfortunately, even to this day, I’m often the first Black woman to achieve a given thing. So I have a responsibility to make sure that I’m not the only one; that I’m not the last. I want to do everything in my power to make sure that other young Black women have access to opportunities to succeed and to thrive as writers. At this point in my career, mentorship is the most important kind of work.

SAVILLE: Ruth Bader Ginsburg talked about how the gates will open to allow more people to get through. I feel that, and so do you. But I often wonder, when exactly will the gates open?

GAY: That’s a good question. The gates are opening in the writing world a little bit, but they’re not opening as widely as people like to believe. An article in the New York Times showed that between 1950 and 2018, only 5 percent of all published fiction was written by people of color. I really thought we’d been making more progress than that. At the same time, there are a lot of white writers who sincerely believe, “I’m white, so there is no way my book is going to get published,” even though white people comprise 95 percent of the publishing world.

SAVILLE: That’s the good thing about data, though, isn’t it? It really shows us the reality of the prejudice. It’s disheartening to see how little has changed, though—the same goes for data about pay inequality.

GAY: Absolutely. Ten years ago, I collected data and found that nearly 90 percent of the books reviewed in the New York Times are by white authors. It’s so important to have hard numbers, because so many naysayers will only believe data. But we can’t just look at the data and say, oh, that’s terrible. Publishers need to respond—not just with editorial fellowships, but with permanent changes. Until they do, we’re going to continue to have these conversations. Diversity and inclusion are not my areas of expertise, but I’m forced to do this type of work because these egregious disparities continue to exist.

SAVILLE: Surely we can do better than this. I’ve noticed that there are loads of women working in the art world. If I do a show in a museum, you can pretty much guarantee that all the people around the table will be women. But still, at the head of the table, the director is almost always a man. It’s like this in nearly every country I show in. For me, female art advisers are the unsung heroes for women artists. They’ve convinced wealthy collectors to increase the diversity of their collections, and have played a huge role in increasing the visibility of a whole range of artists.

GAY: The equation is probably different for art than it is for literature. Only wealthy people can buy unique artworks by major artists. There are a lot more readers.

SAVILLE: In auction houses, “women’s art” is sometimes a category—this sort of pigeonholing happens to people of color too. Often, I think it’s because people don’t know how to speak about the content of what we’re making.

GAY: They don’t think that there is something to talk about beyond the identity of the artist. I think a lot of white people are afraid to critically engage with work by people of color because they don’t want to be perceived as racist if they don’t simply love it, which is so condescending—as if we can’t handle critique. We can and we do, every single day.

SAVILLE: It’s also part of the branding. Identity becomes a way to sell or a way to promote the work, but it then acts as a veil between the audience and the work’s content.

GAY: Do you feel like you are pigeonholed?

SAVILLE: To be honest, I try to ignore those pressures. I’ve got a platform and I’m going to use it however I like. What about you, what is the feedback to your work like?

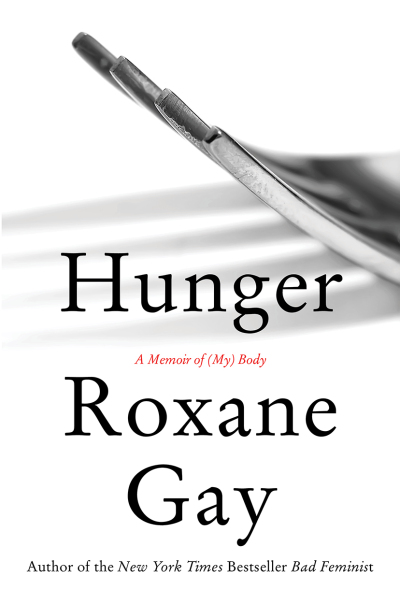

Roxane Gay’s Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, HarperCollins, 2017, 320 pages.

Roxane Gay’s Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, HarperCollins, 2017, 320 pages.

GAY: I get all kinds of feedback. I wrote a book called Hunger (2017), which is about living in a fat body. Some people complained that the book glorifies fatness. At the same time, some fat people have said I am glorifying diet culture and fatphobia. It can be painful when the people you see as your people disagree with you, or they read things into your work that are not there. At times, it seems like I can’t please anyone. But that’s OK, because that’s actually not my job.

SAVILLE: If you say something that’s real, that’s as much as you can do.

GAY: Absolutely. I often tell my students: if nobody is criticizing you, and if nobody is disagreeing with you, then you haven’t done your job. Universal appeal is not my ministry. I’m glad to be an acquired taste.

SAVILLE: You’ve got this amazing confidence, and I’m wondering, does it come from your willingness to reveal vulnerabilities? For me, I’m very conscious that I’m going to die one day, which makes staying brutally, viscerally true seem urgent and worthwhile.

GAY: I mean, some of that confidence is “fake it ’til you make it.” But at the same time, I have really strong boundaries, so if I’m being vulnerable, it’s something that I can handle being vulnerable about. When I wrote Hunger, I knew it would be met with cruelty. But I did it anyway.

SAVILLE: Do you read all the cruelty? Does the negativity get etched into your brain?

GAY: I do read most reviews in reputable publications, but I’m not necessarily going to read someone’s blog post about my books. If a review is critical, I feel my feelings, and then I really think about what the writer said. If it’s reasonable, or if they’re right, I try to do better the next time. But I don’t go looking for petty cruelties.

SAVILLE: I don’t really read the reviews of my shows anymore. I used to, but now, I just get on with it, because they can make you feel a bit miserable.

GAY: That makes sense. I certainly have other forms of criticism in my life: editors and trusted readers.

SAVILLE: I was wondering, would you model for me?

GAY: Oh! I’ve never even considered modeling. . . but, yes, that would be so fun!

SAVILLE: Would you really? I was watching a video of you speaking at the 92nd Street Y in New York, and wow, you’ve got the best thighs I’ve ever seen! We can get together after this stupid virus is over. I’m so excited.

GAY: I’m surprised by my response! I would have never said yes even five years ago. But the older I get, the more I’m like, whatever. It’s not like I need a day job anymore.

—Moderated by Emily Watlington

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/fatness-feminism-representation-1234601645