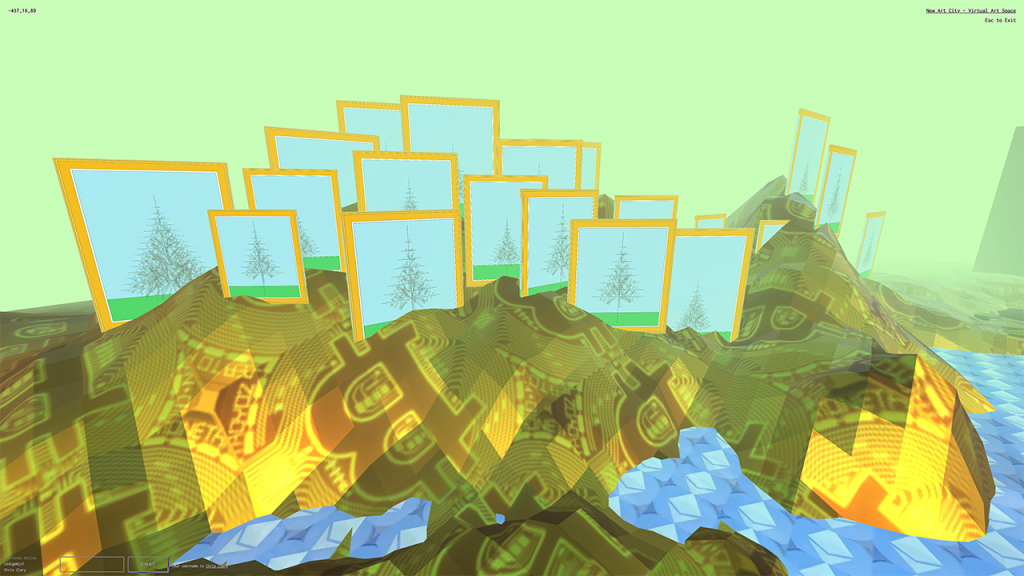

View of “NFS NSFW NFT,” 2021, at New Art City, showing works by Bhavik Singh. Courtesy the artists

View of “NFS NSFW NFT,” 2021, at New Art City, showing works by Bhavik Singh. Courtesy the artists

This past winter, the NFT hype cycle touted the emergence of an art market without gatekeepers, where value was determined by creators and collectors—often the same people—rather than dealers, curators, and advisers who maintain authority by limiting access. But as the market grows it seems like stakeholders in the community have realized that well-kept gates have a wayfinding function. They help audiences navigate a complex field. Artists, galleries, and other interested parties are investing energy in selection, aggregation, and presentation—activities known as “curation,” even if they’re performed without aspects of the old-school gatekeepers’ curatorial work, like historical scholarship and conservation.

The interfaces of popular NFT marketplaces have a little curation built in. On SuperRare, you can see the NFTs in any user’s collection, and click around to get a sense of the scenes and cliques that grow around the site. This functionality flavors SuperRare, the Amazon of NFTs, with a taste of MySpace. But all that clicking takes a lot of time and effort. Top-down curation can offer a more inviting entry point. Several efforts in that direction have cropped up in recent months. Many of these take the form of the classic browser-based exhibition, a walled garden of a website that lets visitors click through a limited selection of artworks, each one furnished with explanatory texts from the curators, like the ones you’d find on the wall of a museum.

The browser-based exhibition has been around since the 1990s, though swathes of its history has been lost due to institutional neglect; click a link for an online show more than five years old and you’re likely to get an error message. Covid-19 shutdowns promised a renaissance of online exhibitions, but for the most part all we got were online viewing rooms, aka OVRs—installation shots of paintings in galleries that no one could visit, arranged on pages that differed little from the documentation you usually find on gallery web sites. The aftereffects of the NFT boom finally made good on that promise, as stakeholders in the crypto space return to the format and reinvent it to emphasize what NFTs can—and can’t—do for digital art.

Shi Zheng, Free Fall Study III, video, 4 min.; in “The Long Cut.” Courtesy Feral File

Shi Zheng, Free Fall Study III, video, 4 min.; in “The Long Cut.” Courtesy Feral File

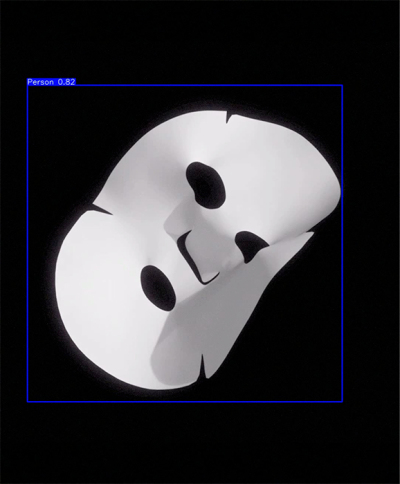

Feral File set the standard. Initiated by artist Casey Reas, the exhibition platform launched in late April. There’s nothing radical about its interface, which presents artworks in an annotated slideshow according to the browser-based exhibition’s conventions, though the design is crisp, cool, and generous with space. New shows organized by invited curators open on an almost monthly basis, each one thematically focused on a particular genre or trend in digital art. The fourth show, “The Long Cut,” opened this week. Curator Iris Long selected seven Chinese artists working with computer-mediated perspectives: from machine vision and language models to astronomical calculations and biometrics.

Each work in a Feral File exhibition is sold as a limited edition, and sales are registered on the Bitmark blockchain. Reviewing “Social Codes,” Feral File’s debut show of generative art, Theodora Walsh wrote that the platform highlights the blockchain’s potential as an archiving tool, using it as a ledger rather than a currency. (Feral File now accepts Ethereum and Bitcoin, but originally priced works only in US dollars.) “When you click the ‘Collect This Work’ button on an artwork’s page, you see a register of purchases,” Walsh wrote. “A quick scan shows that most of the artists in ‘Social Codes’ collected each other’s work.” Feral File demonstrates how NFTs can build a culture of transparency around the traditionally opaque affair of collecting.

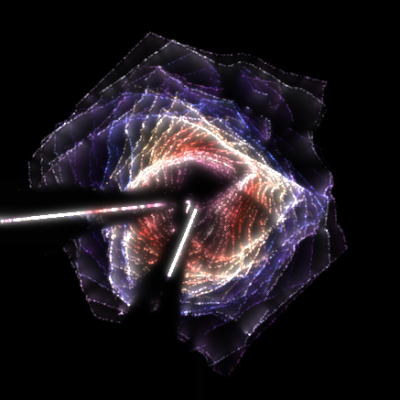

A new platform called JPG, founded by María Paula Fernández, Sam Spike, and Trent Elmore, approaches curation as a way to accrue cultural capital from the blockchain’s record of provenance. Collectors are invited to list the NFTs they own on JPG’s registry. From there, artworks can be organized in exhibitions using JPG’s slideshow interface, allowing collectors to demonstrate meaningful connections among the NFTs they own and any others listed on JPG’s registry. “Deep Time,” curated by JPG’s founders, went live July 28 as a soft launch to demonstrate how the platform looks and what it can do. “Deep Time,” includes some landmark works in NFT history, such as an Autoglyph token by Larva Labs, the collective of creative technologists behind the CryptoPunks avatars. The Autoglyph project was an early experiment in storing the code and output of generative art on the blockchain, rather than putting a link in the block to an artwork stored elsewhere, as is the case for most NFTs. Each Autoglyph is a black-and-white ASCII pattern, reminiscent of plotter drawings made by the first generative artists in the 1960s. “Deep Time” also features some new innovations. Each token in “Entropy,” an animation project by the artist known as 0xDEAFBEEF, degrades as it’s minted, like copies of analog media—a similarity underscored by the grainy, staticky quality of the video’s sound and visuals.

Still from Alexis André’s 720 Minutes #578, a real-time clock generated from a transaction hash on Art Blocks; in “Deep Time.” Courtesy JPG

Still from Alexis André’s 720 Minutes #578, a real-time clock generated from a transaction hash on Art Blocks; in “Deep Time.” Courtesy JPG

The “Deep Time” of the title suggests spans exceeding human lives and generations, alluding to the blockchain’s promise of code that lasts forever. The predominance of generative works in the show, several of which evolve over their iterations, both amplifies and complicates the idea of permanence. It’s a smartly organized exhibition, and it sets a high bar for the platform’s curatorial sensibility. It’s hard to imagine that most collector-generated exhibitions will meet it—and easier to envision how the openness of the registry can be abused. The idea underlying JPG is that works will gain cultural value through meaningful juxtapositions with other NFTs. In theory, a collector could game the system by putting cheap NFTs alongside Beeples and CryptoPunks and Paks. JPG hasn’t put any measures in place to give artists or collectors whose work is on the registry a say in how it’s shown. Though they approached “Deep Time” with thoughtfulness and care, reaching out to collectors and the artists whose work is included, the founders are excited to experiment with permissionless protocols. And so the kind of curation JPG is proposing is more Pinterest than museum: it lets everyone be a gatekeeper. It’s curation without expertise—or at least it swaps out institutional verification for faith in the power user, and a belief that a community of engaged collectors will regulate itself.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is “Pieces of Me,” an online exhibition that opened in April for an indefinite run to assert the importance of an institution’s centralized curatorial care in a rapidly shifting environment for digital art. The institution in question is Transfer Gallery, founded by Kelani Nichole in 2013. Transfer focuses on brick-and-mortar presentations of computer-based art, so this is a one-off show, not a platform like Feral File or JPG that will host more down the line. Transfer has organized browser-based exhibitions in the past—the most recent precedent being “Well Now WTF?,” launched in April 2020 to spotlight digital art as all galleries were going online during the pandemic. “Pieces of Me” was also conceived as a response to a crisis: “an offering to the hungry gods of DeFi [decentralized finance]” that looks critically at the NFT boom and its impact on artists’ careers, markets, and psyches.

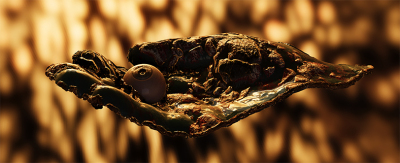

Auriea Harvey, Stygian Hand, 2021, HTML artwork with 3D Model. Courtesy Transfer Gallery

Auriea Harvey, Stygian Hand, 2021, HTML artwork with 3D Model. Courtesy Transfer Gallery

“Pieces of Me” is a sprawling effort, co-curated by Nichole and Wade Wallerstein, with works by forty-nine artists and collectives. These are divided into eight categories, the titles of which evoke aspects of the relationship between artist, work, and audience with the earnest angst of pop song lyrics: “Who I Am,” “Blow It All,” and “I Don’t Belong Here / This Is Where I Belong,” among others. These are also meant to convey artists’ varying attitudes toward the NFT market. Some works were made in response to the curators’ prompt. Cassie McQuater’s This is Not For Sale is a text-only file that reads: “This relationship is / worth more to me than / money.” Available for free download in an unlimited edition, it speaks to each reader about how much the artist values their time and attention. But most artworks in “Pieces of Me” were made independently of the show, offered by artists for sale and possible minting. Serwah Attafuah’s Galileo’s Gaze (2018) is a fantastical portrait of the artist as a winged goddess of victory, rising proudly despite the gold chains wrapped around her and the rebellious cherubs clustered at her feet. Auriea Harvey’s Stygian Hand (2021) models a withered palm holding a darkly gleaming orb. The image alludes to the witches of Greek myth who shared one eye.

The high-concept structure of “Pieces of Me” can make it hard to identify common threads and meaningful connections. Works by Attafuah and Harvey are two of several that deploy 3D graphics to refresh the tropes of fantasy art, and use ancient archetypes to frame contemporary problems of identity. They resonate with the mystical language of “offerings” in the curatorial statement. But Attafuah’s Galileo’s Gaze is framed as a statement on “sovereignty,” in the section “Blow It All.” Harvey is categorized in “I Don’t Belong Here / This Is Where I Belong,” as an artist who avoids binaries—presumably because she has enjoyed success by selling works as NFTs but feels ambivalent about it. What this has to do with Stygian Hand, I can’t say. These relationships aren’t always clarified in the text accompanying each work. Because the exhibition’s organizing principles are not based in the content of the work, “Pieces of Me” ends up ceding more importance than it probably should to the NFT, which figures not only as an option available to collectors but a conceptual bugbear looming over everything.

A generous take would be that the unwieldiness of “Pieces of Me” forces viewers to slow down, think, and make their own connections—a counterpoint to the frictionless ease touted as a benefit of the NFT market. And the exhibition does incorporate some infrastructure to support this position. To make the viewing experience more social than a clicking of links, Transfer hosted regular gallery hours, where visitors could chat with the curators in the video lounges that Nichole developed at the start of the pandemic as a Zoom alternative. Though these sessions recently ended, four months into the show’s run, they foregrounded the gallery’s presence and its role in determining how digital art is understood, collected, and cared for.

A view of the virtual environment for Epoch Gallery’s exhibition “Freeport.” Courtesy Epoch Gallery

A view of the virtual environment for Epoch Gallery’s exhibition “Freeport.” Courtesy Epoch Gallery

The classic browser-based exhibition presents works one at a time. A virtual exhibition in a browser can create sightlines, arranging digital objects in a simulation of physical space. Virtual galleries increased in number at the same time OVRs proliferated, but for the most part they offered little more than their 2D counterparts—just the fish-eye perspective already available in the virtual museum tours powered by Google’s Streetview technology. Artist-driven projects have delivered more engaging viewing experiences by going beyond the virtual white cube.

One such project is Epoch Gallery, launched by Peter Wu in April 2020. Wu designs beautiful, haunting environments, reminiscent of the tableaux from the 1993 computer game Myst, to be navigated with the same kind of point-and-click interactivity. The settings for virtual exhibitions on Epoch have included the ruins of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and a deconstructed white cube floating like wreckage off the coast of a city. “Freeport,” which opened June 12 and will remain Epoch’s featured exhibition through October 1, is set in a brutalist building. The exhibition’s title suggests that this is a storage space for art, that limbo where works possessed as speculative investments languish. The building is run down, and weeds crawl in its open doors—the art dumped there has long been forgotten. The rubber-faced animated paintings in Neïl Beloufa’s The Freeport Song (2021) sing forlorn tunes out of sync, as if unable to hear each other. Hearkening back to the age of exploration, Juan Covelli’s Terra Incognita (2019) offers a fantasy of the New World, rendering its exotic climes in a theater-piece backdrop, animations, and 3D sculptures. Alice Bucknell’s Swamp City (2021) is a showroom for a luxury resort in a post-apocalyptic Everglades. Its cheery videos and signage are tucked in dark storage spaces. Wu’s deteriorating freeport is modeled after one in Luxembourg, so Covelli’s and Bucknell’s contributions exaggerate the sense of geographic and temporal displacement.

View of “Freeport,” 2021, at Epoch Gallery, showing Juan Covelli’s Terra Incognita (2019). Courtesy Epoch Gallery

View of “Freeport,” 2021, at Epoch Gallery, showing Juan Covelli’s Terra Incognita (2019). Courtesy Epoch Gallery

Some of the artists included in “Freeport” have engaged with crypto before. For his exhibition “Digital Mourning,” which closed last month at Pirelli HangarBiccoca in Milan, Beloufa gave sculptures personalities by dubbing them NFTs, and he minted a virtual version of one on SuperRare. Bucknell has written on the blockchain’s promise of decentralized organization and what it can mean for the art world. But the sixteen works in “Freeport” aren’t NFTs. The whole exhibition is. Collectors can purchase a video presenting a slideshow of installation views. “Freeport” connects the junkspace of art storage to the economics of crypto art, comparing the ways in which both convert art into a financial tool. But by minting the show rather than individual pieces, Wu asserts the value of curation, asking potential patrons to support the production of exhibitions rather than claim works.

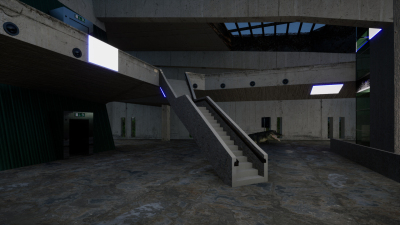

New Art City is another artist-run virtual exhibition platform that launched in 2020, founded by Don Hanson. Unlike Epoch, it’s designed as toolkit that others can use. A user-friendly back end streamlines the process of assembling a virtual show by offering tools for uploading 2D and 3D artworks and arranging them in the exhibition space “NFS NSFW NFT,” which opened on New Art City July 20, is organized by Christopher Clary, Pearlyn Lii, and Mark Ramos, three artists who are residents at New Inc, the art-and-tech incubator at the New Museum in New York, on Rhizome’s Art & Code track. The show includes works by the curators and eight other artists, in four interconnected salons—one corresponding to each of the title’s abbreviations in the title, plus a hub with statements and essays. The spaces of “NFS NSFW NFT” are cartoonish and vertiginous, nothing like a white cube or any other real-world space. The terrain is riddled with craggy slopes, shaped somewhat like the mountains in Chinese landscape painting, and skinned with graphics related to the show’s themes. The hills in the NFS glow with gilded Bitcoin logos, and blue Ethereum symbols flow through lakes and rivers. Content warnings cover the slopes of the NSFW salon, making the terrain feel dark and hostile.

View of “NFS NSFW NFT,” 2021, at New Art City, showing works by Nahee Kim and Pearlyn Lii. Courtesy the artists

View of “NFS NSFW NFT,” 2021, at New Art City, showing works by Nahee Kim and Pearlyn Lii. Courtesy the artists

“NFS NSFW NFT” addresses topics that occupy many artists now: how the body is mediated by technology, how the market captures value, and how artists navigate these systems to survive. Several of the works in the show have been minted as NFTs, like co-curator Lii’s “Real Girlfriend” portraits of doe-eyed and pliable CGI women. Episodes of Ziyang Wu’s haunting sci-fi animation “A Woman with the technology” (2019) are being minted over the course of the show’s run. But works like Bhavik Singh’s spindly generative trees that renders on virtual screens in the NFS salon are, as the section header suggests, not for sale.

The organizers promise to mint a video walkthrough of the show on Foundation, with the caveat that the MP4 file will be compressed to fit the marketplace’s 50 MB limit, and they’ll embrace whatever distortions this brings. As Wu does with “Freeport,” Clary, Lii, and Ramos imagine the whole show as an NFT to comment on what the technology does to art and how it’s viewed. These virtual online exhibitions dramatize the act creating a context for art through curation because they entail designing environments from the ground up. They use visual means to accomplish what slideshow-style online exhibitions do through text. Both types give hope that critical thought about digital art can catch up with the recent growth of its market.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/nfts-curation-online-exhibitions-crypto-art-1234601534