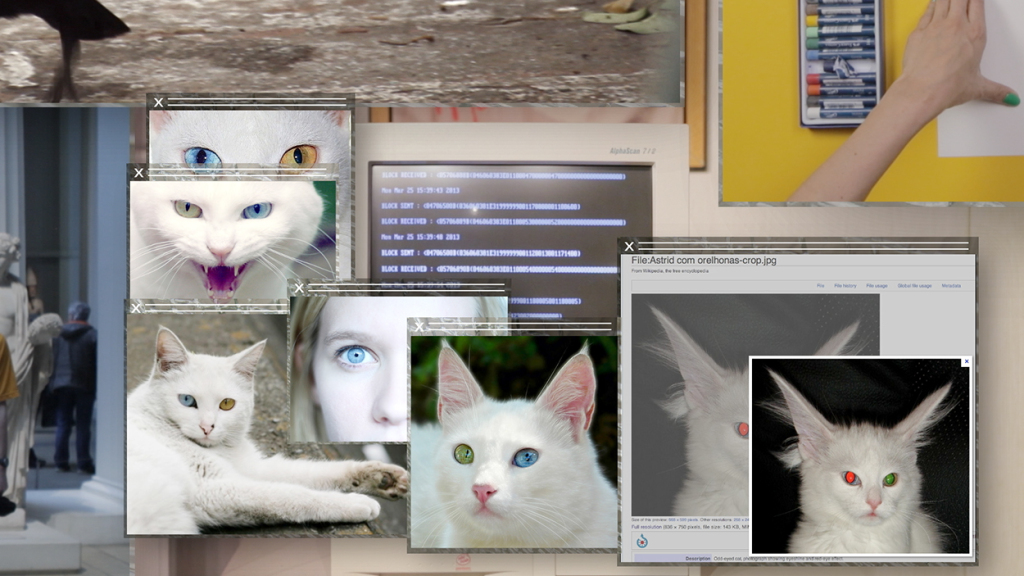

Still from Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue, 2013, digital video with sound, 13 minutes. Courtesy the artist. © ADAGP Camille Henrot

Still from Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue, 2013, digital video with sound, 13 minutes. Courtesy the artist. © ADAGP Camille Henrot

In Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life (UC Press, 2020), Janet Kraynak paints a grim picture of a world where the imperatives of surveillance capitalism have preempted democratic ideals. Thanks to social media, the public sphere has been replaced with emotional outbursts and opportunities for consumption. Museums have followed suit, relinquishing their mission to enlighten and challenge the public and offering mere content instead. The one ray of hope is art, which, Kraynak believes, is unique as a vehicle for complex, critical thought. She gives in-depth readings of works by Bouchra Khalili, Camille Henrot, Glenn Ligon, and others, demonstrating how they address technology’s reshaping and imposition of power. An antagonistic counterculture of contemporary art, Kraynak says, is a bulwark against a digital dark age. But she doesn’t reckon with the limits of art’s criticality: its poor record when it comes to fomenting wide-scale social change, in part due to its circumscription to rarified venues like Columbia University, where Kraynak teaches in the art history department, and the Venice Biennale, where she encountered many of the works she writes about.

Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life treats contemporary art as a relatively static category. In surveying works made over the last three decades, Kraynak offers a narrative not of how art is changing but of how art registers social and technological change. She engages with some texts on the history and theory of art, but the primary corpus she cites is the literature of critical technology studies, the work of thinkers like Tara McPherson, Lisa Nakamura, and Shoshana Zuboff, who describe how technology reinforces and exacerbates forms of racial and economic inequality. When Kraynak draws on Claire Bishop’s critique of participatory art—that its 1960s connections to emancipatory politics have been severed as institutions repurpose it as prescriptive entertainment—she contextualizes it in terms of how techno-utopian visions of an open, networked society have been exploited to construct large-scale mechanisms of corporate surveillance and control. Kraynak is uninterested in the use of digital media as an artistic medium or material, and how this has affected artists’ practices. Instead, she deliberately chooses to consider works in a variety of mediums, arguing that by eschewing categories she advances an understanding of digitization as “a social, historically evolving form.”

Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life by Janet Kraynak, University of California Press, 2020, 291 pages, $65.

Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life by Janet Kraynak, University of California Press, 2020, 291 pages, $65.

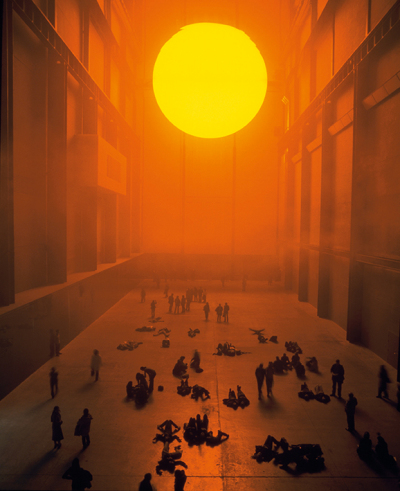

For these reasons, Kraynak’s book is less interesting as a study of contemporary art than as an examination of the art world and how its institutions have changed in step with the digitization of everyday life. The most compelling chapter is the third one, “Therapeutic Participation and the Museological User,” which charts a shift in museum priorities from displaying art toward providing services. This transition, she argues, began in the late 1990s, driven by the growth objectives of development departments and abetted by curators and artists whose experiments with relational aesthetics accelerated the viewer’s transformation into a user. (Maybe this is why conventional models of art history aren’t useful for Kraynak: in the twenty-first century, the avant-garde is the bad guy.) Olafur Eliasson’s The weather project (2003), Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Rooms, and other immersive installations that have become museums’ most popular attractions in the last two decades create environments where art is not an object of contemplation but a backdrop for self-actualization, where the collectivity of the museum public breaks down into the individualities of selfie-taking “museum users.” In becoming more “democratic and accessible,” Kraynak writes, the museum becomes indistinguishable from other venues of the experience economy, rather than “an active productive public sphere.” She exposes the insidiousness of fun with such rigor that readers will think back on moments when they enjoyed themselves in a museum with guilt and regret.

Olafur Eliasson, The weather project, 2003, monofrequency lights, projection foil, haze machines, mirror folk, aluminum, scaffolding, 87 ½ by 73 by 510 feet; at Tate Modern, London. Courtesy the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, Tonya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Los Angeles. Photo Andrew Dunkley and Marcus Leith

Olafur Eliasson, The weather project, 2003, monofrequency lights, projection foil, haze machines, mirror folk, aluminum, scaffolding, 87 ½ by 73 by 510 feet; at Tate Modern, London. Courtesy the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, Tonya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Los Angeles. Photo Andrew Dunkley and Marcus Leith

For all Kraynak’s thoroughness, she leaves out any consideration of the weaknesses that made the museum vulnerable to these profound changes. If the museum was effective as a public sphere, then why did it succumb to the encroachment of digitization? Kraynak does not subject the museum to the same skepticism she applies to digitization, even though it’s an epistemological technology in its own right, as Donald Preziosi and others have argued. Instead, she blames social media, and the mob mentality it fosters. In the introduction, Kraynak despairs that museums are kowtowing to cancel culture. Her exemplary instance of this is the controversy around the Guggenheim Museum’s exhibition “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World.” The museum removed the work by Huang Yong Ping from which the exhibition took its title—a terrarium sculpture where lizards and amphibians fight to the death and eat each other’s remains—following an online campaign by animal rights activists protesting the piece’s cruelty. Kraynak also mentions the calls to pull Dana Schutz’s Open Casket from the 2017 Whitney Biennial and the Walker Art Center’s decision to take down Sam Durant’s monumental sculpture Scaffold (2012), which re-created the Minnesota gallows where 38 Dakota men were hung in 1862. But these stories are relegated these to endnotes, where Kraynak relates them in a dry, just-the-facts manner—a sleight of hand that saves her the difficulty of taking a stance against the protests of Black artists and the Dakota nations that could be construed as racist or reactionary.

Kraynak insists in her introduction that she holds no romantic nostalgia for some analog past. But her book’s main flaw is not nostalgia but credulity—an unquestioning faith in the traditional museum as a bastion of democratic values, despite her occasional, de rigueur acknowledgments of the museum’s roots in colonialist extraction and oligarchic accumulation. This faith goes hand in hand with her dedication to hermeneutics. Kraynak’s rigor gives her arguments a staunch seriousness, but it also seems to blind her to how elitism is anti-democratic in its own way, or how dense academic prose like hers might impede the exchange of knowledge. “I don’t tweet,” she writes in the first words of her introduction. “I don’t share and I don’t like. I don’t friend and I am not a fan.” Maybe this keeps her from understanding the double consciousness of those who do. If skepticism is the strongest medicine that art has to offer us, why not devote some of this exacting attention to learning how it inhabits the arenas of digitization, or how it generates new forms of collectivity and criticality there, in addition to insisting on the relevance of the old ones?

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/janet-kraynak-contemporary-art-digitization-everyday-life-1234602774