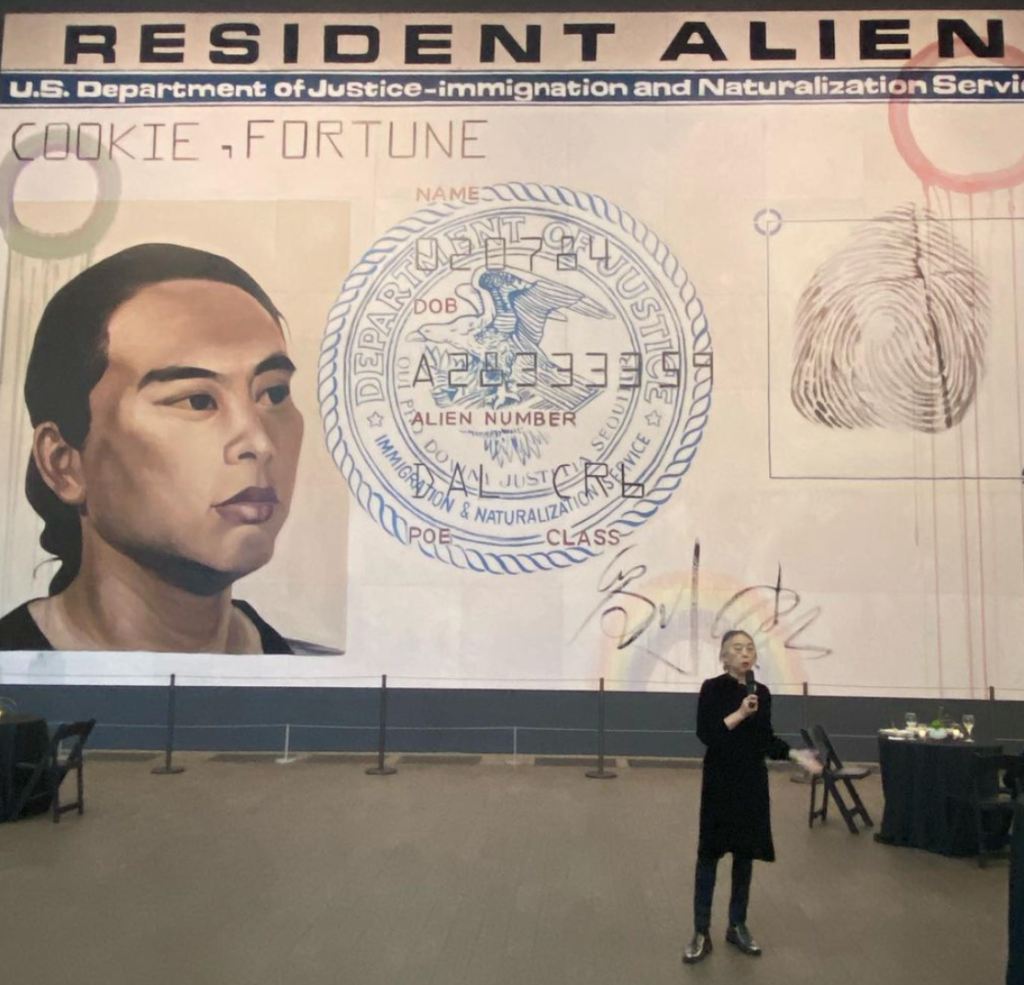

Hung Liu at the opening of her installation “Golden Gate” at the de Young Museum. Courtesy Thomas Campbell via Twitter

Hung Liu at the opening of her installation “Golden Gate” at the de Young Museum. Courtesy Thomas Campbell via Twitter

Hung Liu, an artist whose childhood in Maoist China inspired intimate explorations of identity, has died at the age of 73. In her work, Liu often translated photographs, primarily from her family history, into large-scale paintings or installations. Her 1994 painting Father’s Day takes as its source an image of a young Liu with her father, taken during a visit to a rural labor camp he had been sent to after rebelling against the Communist regime. In Resident Alien (1988), she recreated her own green card as a painting, with a few notable alterations: a different name reading “Fortune Cookie,” and a birth date changed from 1948 to 1984, referencing both the year she immigrated to America and its Orwellian parallels.

A monumental recreation of that work is currently on view at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Thomas Campbell, director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, wrote on Instagram that Resident Alien, “now towers over the [museum’s] Wilsey Court, a fierce testimony to the impersonal way that the U.S. ‘others’ immigrants as ‘aliens,’ and a poignant temporary memorial to her passing.”

Hung Liu was born in Changchun, China, in 1948 and came of age during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. She was the granddaughter of a scholar and her father was a counter-revolutionary. She was one of millions of urban youths sent to the countryside for an agrarian “re-education.”

After four years of hard labor in rice and wheat fields, Liu was allowed to study art in Beijing, but she remained determined to leave her home country. After years of going through the arduous process to obtain a passport, she finally got one and emigrated to the U.S. In her mid-30s, Liu arrived in 1984 with about $20 and a few family photos and letters that had not been lost during the era of the Cultural Revolution. Liu’s immigration story had a lasting influence on her art, with her later works often taking I.D. cards and immigration papers as subjects.

Shortly after her arrival in California, Liu enrolled in the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego. There she began experimenting with canvas, first applying thick layers of oil paint, then washing the canvas with linseed oil. The linseed “tears” streaked and dripped over the base layers of paint, resulting in fragmented portraits that evoked her own fraught relationship with her culture.

She called her style “weeping realism” since it infused the skills she learned studying Socialist Realism in China with a deep empathy for those failed by the country’s bureaucracies. In her first trip back to China in 1991, she discovered a cache of pre-revolutionary photography of prostitutes, prisoners, entertainers, refugees, and laborers. In her paintings, she balanced their desolation with Buddhist symbols of hope and happiness, lotus blossoms, and cranes in flight.

“I hope to wash my subjects of their ‘otherness’ and reveal them as dignified, even mythic figures on the grander scale of history painting,” Liu once wrote of her ambitions.

In 2019, the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing cancelled a show of her work after Chinese authorities refused to issue required import permits. No official reason was given for the decision, though in an interview with the New York Times, Liu said the censorship board was particularly concerned with nine works, including a self-portrait featuring the artist as a young woman with a rifle slung over her shoulder and another work that depicted a group of schoolgirls in uniforms wearing gas masks that was based on a photograph of an air raid during Word War II.

The exhibition would have also included a series of paintings based on Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era photography, including Lange’s famous Migrant Mother (1936). Lange’s black-and-white images were recreated by Liu in a palette of washed gray and yellow contrasted by bright streaks of orange and blue.

“Of course my work has political dimensions, but my focus is really the human faces, the human struggle, the epic journey,” Liu said at the time, adding, “I sincerely feel like all I’m doing is enshrining the anonymous working class who never had a voice.”

The first major retrospective of her work on the East Coast, “Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands,” will open later this month at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. In a statement, NPG director Kim Sajet said Liu’s “extraordinary artistic vision reminds us that even in the midst of despair, there is hope, and when people help each other, there is joy. She believed in the power of art—and portraiture—to change the world.”

Sajet added that during a recent studio visit with Liu, the artist “communicated her belief in the exhibition’s potential to convey her hopes for the future—a future based on a foundation of empathy for others.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/hung-liu-artist-dead-1234601127