View of “DICKERING,” 2021, at Hannah Hoffman, showing Untitled (Family #1), 2021. Courtesy the artist

View of “DICKERING,” 2021, at Hannah Hoffman, showing Untitled (Family #1), 2021. Courtesy the artist

Someday, when art historians survey the art of the Covid-19 pandemic, attempting to chronicle aesthetic trends and salient themes, a section on domestic photography might include Talia Chetrit’s latest images. In her arresting exhibition “DICKERING” at Hannah Hoffman gallery in Los Angeles, Chetrit presents ten new large-format photographs that expand on her semi-autobiographical investigations of gender, sexuality, and representation, now with a stronger emphasis on the dynamics at play in familial relationships.

A few portraits of her boyfriend, their toddler son, and the artist herself—all in varying stages of undress—counter familiar heteronormative images of domestic bliss. In the black-and-white photograph Untitled (Family #1), 2021, the gangly, hairy dad appears in an elegant skirt with BDSM accoutrements—maybe one worn by the photographer to a glamorous opening in pre-pandemic times. Looking with an opaque expression toward the camera, he foppishly reaches down to stuff a bottle into his child’s mouth. Suspended from the wall behind them are four spiky fire pokers—objects consistent with the fetish-inspired outfit. It’s an unconventional and transgressive scene of childcare in which the feminized boyfriend functions as both sex object and domestic worker; quarantine, we are reminded, offered many people a reprieve from certain social and sartorial norms. But the photo also frames gender as a form of amusement, a low-key afternoon activity of dress-up—or, rather, dress-down. One must also remember that, for the boyfriend—a cisgender man in the quiet intimacy of his home—little is at stake in putting on a skirt. The same act in a more public setting has the potential to be not only a visual articulation of gender identity, but also a political act with consequences.

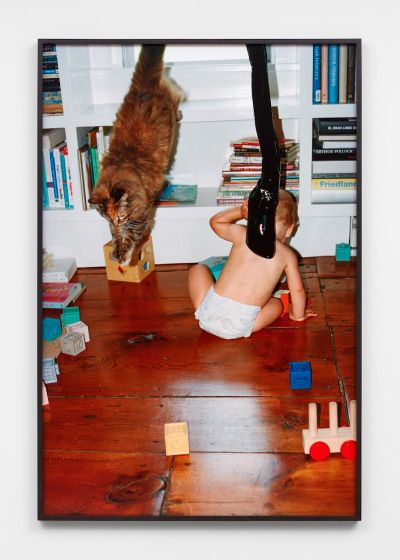

Talia Chetrit, Cat Boot Baby, 2021, inkjet print, 60 by 40 in. Courtesy the artist

Talia Chetrit, Cat Boot Baby, 2021, inkjet print, 60 by 40 in. Courtesy the artist

Themes of sexual play and familial triangulation are also central to many of Chetrit’s other photos, including Cat Boot Baby (2021), which captures the diapered toddler entertaining himself with blocks alongside a feline companion in mid-leap. The cat’s tail stretches out of the frame and seems to curve back into the shot in the form of a black leather boot that partly obscures the view of the baby’s head, and possibly even knocks against him, as his body language suggests. The boot—an overdetermined erotic signifier with which Chetrit has long been preoccupied—is more than a sneaky insertion into a mundane scene of early childhood; the photographer effectively uses the object to underscore rather than conceal the presence of sex in the American home. Other images focus on similarly evocative feminine objects, including one high heel standing erect inside another, a dainty pearl crucifix dangling from a tyke’s bike, and a luminous rubber nipple. Taken together, the carefully curated photographs play with and expand on the symbols and norms of white middle-class heterosexual desire and family life, rather than undoing or doing away with them altogether.

Yet even if the world Chetrit inhabits seems thoroughly heterosexual, her work is indebted to, and at times emulates, queer photographers’ practices that remap the intersections of the erotic, the domestic, and the familial. To be sure, the photos of her partner in a dress might produce valuable alternative visions of heterosexual relationships and modes of eroticism, but they can also read as facile appropriations of queer imagery, as uninspired photos purely intended to shock. The show’s emphatic gerund of a title, “DICKERING,” which generally means to haggle over something, calls to mind a negotiation of these competing interpretations of Chetrit’s work. And perhaps this inconclusive back-and-forth exchange is the reason her exhibition is compelling.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/talia-chetrit-hannah-hoffman-1234600995