Louise Fishman. Courtesy Karma

Louise Fishman. Courtesy Karma

Louise Fishman, whose stylish paintings synthesized modernist abstraction with her identity as a queer Jewish feminist, died in New York on Monday at 82. A representative for Karma, the New York gallery that represents her, confirmed her death.

“The world has lost a formidable painter, activist and friend, whose pursuit of individual freedom and personal expression was her primary motivation as an artist,” Karma wrote in a statement posted to Instagram. “Her death leaves a tremendous void in the art world.”

At first glance, Fishman’s abstractions, many of which feature dense layerings of thick strokes arranged in all-over compositions, appear to be in line with those of white male painters of the first half of the 20th century. Yet Fishman’s paintings tweak those artists’ formulae in subtle yet profound ways, showing how a gestural paint stroke could be intimately connected to one’s identity. In the postwar era, Abstract Expressionists engineered a style predicated on the fact that their paintings referred only to themselves—what was portrayed was believed to contain no references to an artists’ identity or experiences, or even to the world from which it was born. Fishman began subverting this idea in her art during the 1970s. Drawing on her experiences with women and lesbian activism, she began to imbue her paintings with feminist ideals.

“When I moved to New York after graduate school, I thought I was going to meet the Abstract Expressionists,” she told Artforum in 2016. “I found out very quickly that there was no place for me, though; I wasn’t going to be sleeping with Milton Resnick or any of those guys for passion, for love, or to become an artist. My involvement with the women’s movement started out as a strict practice of feminist consciousness-raising, and then I got involved in the lesbian movement, which really changed my life. I blossomed in a way I don’t think I would have without it.”

For much of her career, Fishman’s art went under-recognized by the mainstream art world, but in recent years, it has been the subject of various solo shows, including surveys at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, and Cheim & Read gallery in New York, her longtime representative. (Disclosure: In 2015, I wrote a catalogue essay for Fishman’s Cheim & Read show.)

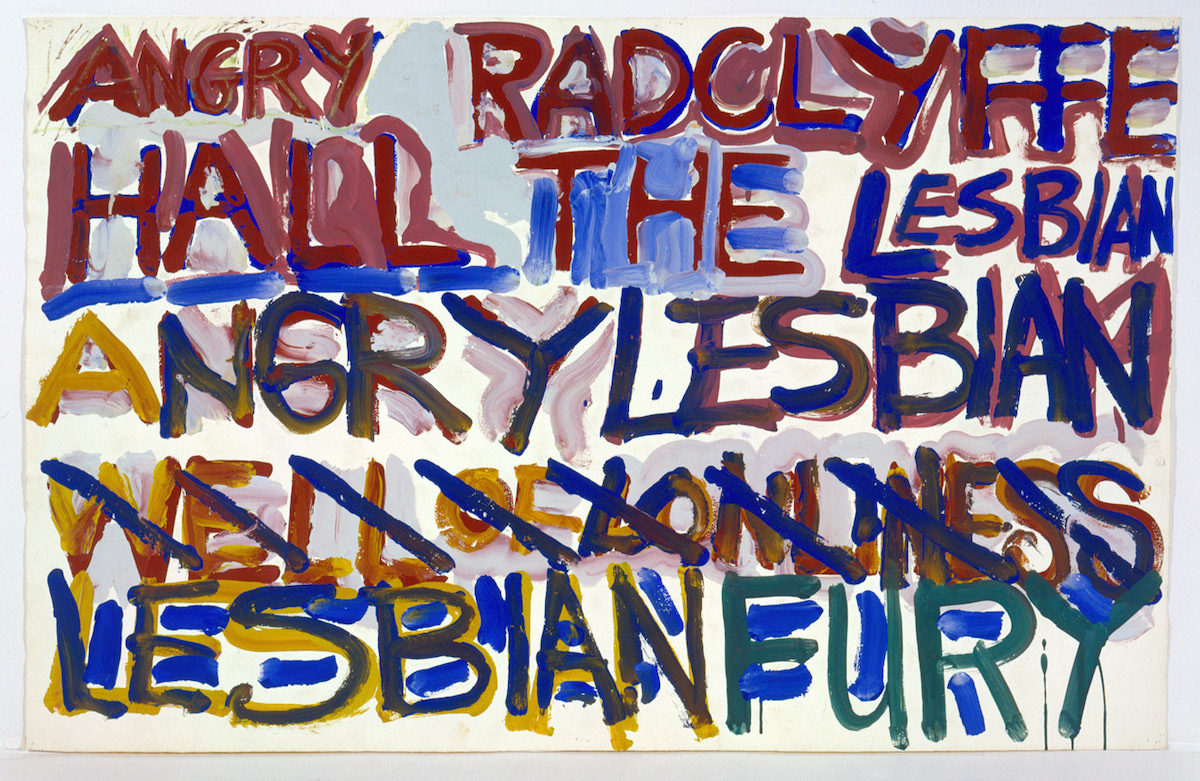

Louise Fishman, Angry Radclyffe Hall, 1973. Courtesy Karma, New York

Louise Fishman, Angry Radclyffe Hall, 1973. Courtesy Karma, New York

For a series begun in 1973, known as “Angry,” Fishman reflected on her own frustration with a patriarchal world that oppressed women by scrawling the names of famous women above abstract backgrounds. One in shades of beige and blue referring to the actress Marilyn Monroe reads “ANGRY MARILYN”; another is filled with crosshatched green strokes and alludes to the poet Gertrude Stein reads “ANGRY GERTRUDE.” Still others refer to Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia founder Ti-Grace Atkinson, the dancer Yvonne Rainer, and Fishman herself. She returned to the series in 2008 for a related body of work called “Serious Rage” that picks up the 1973 series’ themes for a new era, focusing on modern-day figures like Hillary Clinton.

Working during an era when painting was being labeled a dead medium by many critics and curators, Fishman boldly continued to create gestural abstractions. But she did so with her own twists on the medium, as if in refusal of its very contentions. During the ’70s and ’80s, she often chose to use not a paintbrush but a palette knife, and she frequently painted on materials like linen and wood instead of canvas. Buddhism came to be a core part of her artwork, as did Chinese calligraphy.

At the same time, she was also exploring her Jewish identity in her work. Her 1973–74 work Jewish Star Painting, for example, places her name inside a Star of David. Other paintings from this period allude to her Ashkenazi heritage and the horrors inflicted upon Jews during the Holocaust by more abstract means.

In a 2012 essay published by Art in America, painter Carrie Moyer suggested that Fishman was explicitly suggesting that Judaism and abstraction could be connected. “Unlike the formal and material signifiers of gender that she introduced into her work during the women’s movement period (i.e., hand dyeing, sewing, patchwork, domestic scale), the ostensible markers of Jewish cultural identity are harder to identify in the arena of painting,” Moyer wrote. “After all, Abstract Expressionism, a movement long dominated by Jewish artists and critics, was ultimately naturalized as a triumphant American art form and represented by Jackson Pollock, a goy from Wyoming.”

Louise Fishman, Ballin’ the Jack, 2019. Courtesy Karma, New York

Louise Fishman, Ballin’ the Jack, 2019. Courtesy Karma, New York

Louise Fishman was born in Philadelphia in 1939. Both her mother and her aunt were artists, and she felt inclined to follow their lead. She attended the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia and then went to University of Illinois, Champaign for graduate school, earning her M.F.A. in 1965. She later moved to New York, where she encountered hard-edge abstraction by Kenneth Noland and his ilk—a mode she herself initially sought to emulate. (With the exception of a brief foray into sculpture, Fishman worked almost exclusively as a painter throughout her career.)

Louise Fishman, Mondrian’s Grave, 2018. Courtesy Karma, New York

Louise Fishman, Mondrian’s Grave, 2018. Courtesy Karma, New York

Involvement with feminist groups such as Redstockings, W.I.T.C.H., and the New York Feminist Art Institute caused Fishman to see how art history had historically been dominated by men, triggering a shift in her work. She forced herself to think more explicitly about her own identity was related to her art. In 1973, Whitney Museum curator Marcia Tucker did a studio visit with the artist and later curated Fishman’s work into the Whitney Biennial, where a small painting of hers appeared beside a giant work by none other than Noland.

“That Noland was probably 20-feet-long,” Fishman told Artsy in 2015. “And my little painting really stood right up to that Noland; I was so pleased.”

From the ’80s onward, Fishman’s work grew more allusive, relying on various colors and materials to reference a range of people, places, and things spanning centuries and continents. Works from the late ’80s paid homage to her visits to the Auschwitz and Terezín concentration camps in Poland and Czechoslovakia (now Czechia), respectively, by integrating rubble found at both into her paintings.

In 1990, her upstate New York studio burned down, so she relocated to New Mexico. She became close with Agnes Martin, who had lived in Taos since the ’40s, and Martin’s grids wound up informing Fishman’s work in the years after.

A series of paintings made in the early 2010s began to make prominent use of shades of blue—a response, Fishman said, to a 2011 visit to Venice with her partner Ingrid Nyeboe, whom she married the year after. In a 2012 interview with the Brooklyn Rail, Fishman recalled that the blue hues of these works variously alluded to the ocean surrounding the Italian city, Titian paintings, and Nyeboe’s eyes.

“My experience in Venice and the work that followed could be considered comparable to religious conversion, although it has nothing to do with religion,” she said. “If I couldn’t introduce new experiences, materials, ideas into my work, I would be bored and there would be no reason for me to continue.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/louise-fishman-painter-dead-1234599995