The heaviest rain in 70 years has fallen on Greenland’s snowy summit, heightening fears about how rapidly the ice sheet is warming.

Precipitation fell as rain and not snow last Saturday, dumping an ‘unprecedented’ 7 billion tons of water after temperatures at the summit rose above freezing for only the third time in less than a decade.

It was the heaviest rainfall on the ice sheet since records began in 1950, according to US scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The heaviest rain in 70 years has fallen on Greenland’s snowy summit, heightening fears about how rapidly the ice sheet is warming. Pictured, icebergs float away to sea near Kulusuk, Greenland, in this photo from 2019

HOW GREENLAND’S ICE SHEET LOST 8.5 BILLION TONS OF MASS IN ONE DAY

Only last month Greenland’s ice sheet lost enough ice in a single day to cover Florida in two inches of water.

The extreme melting, which occurred on July 27, was caused by heatwaves in northern Greenland that raised temperatures to more than 68 degrees Fahrenheit – double the average summer temperature, according to the Danish Meteorological Institute.

While the 8.5 billion tons of surface mass was less than the record single-day ice melt in 2019, which was 12.5 billion tons, last month’s event covered a larger area.

Scientists have estimated that melting from Greenland’s ice sheet has caused around 25 percent of global sea level rise seen over the last few decades.

If all of Greenland’s ice were to melt, the global sea level would increase by another 20 feet – but this is not expected to happen anytime soon.

Advertisement

Such was the scale of the downpour, the amount of ice mass lost on Sunday was seven times higher than the daily average for this time of year.

Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado, told CNN this is evidence Greenland is warming rapidly.

‘What is going on is not simply a warm decade or two in a wandering climate pattern,’ Scambos told CNN. ‘This is unprecedented.’

He added: ‘We are crossing thresholds not seen in millennia, and frankly this is not going to change until we adjust what we’re doing to the air.’

Earlier this month a bombshell UN report on climate change issued a ‘code red’ warning for humanity, saying the Earth was likely to warm by 1.5C within the next 20 years — a decade earlier than previously expected.

It also found that the burning of fossil fuels was to blame for Greenland melting over the past two decades.

Only last month, the Greenland ice sheet lost 8.5 billion tons of surface mass in a single day, enough ice to cover Florida in two inches of water. It was the third extreme melting event in the past decade.

Analysis of satellite data also revealed that the ice sheet melted more in 2019 than during any other year on record, losing a total of 532 gigatonnes of its mass.

Another study by the University of Leeds revealed that a record-breaking 28 trillion tonnes of ice — enough to cover the whole of the UK in a sheet over 300 feet thick — melted from the face of the Earth between 1994–2017.

The accelerating melt — which continues to get worse — has been driven largely by steep increases in losses from the polar ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland.

Ice melt serves to raise sea levels across the globe, increases the risk of flooding to coastal communities and endangers natural habitats that wildlife depend upon.

Melt from the Greenland ice sheet is one of the largest contributors to rising sea levels and presently contributes an increase of around 0.03 inches (0.76 mm) annually.

Last year a separate study revealed that Greenland’s glaciers have already passed what researchers have called the ‘point of no return’.

The experts warned that this means the ice would now continue to melt away even if global warming could be completely stopped.

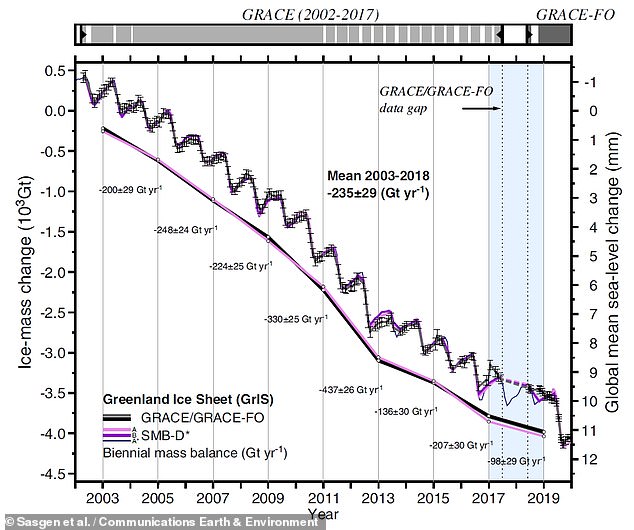

Pictured, the extent of Greenland’s ice loss over time as recorded by the Grace missions. The annual fluctuations represent summer and winter

Earlier this month a report by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was produced by 200 scientists from 60 countries.

Drawing on more than 14,000 scientific papers, the review included the latest knowledge on past and potential future warming, how humans are changing the climate and how that is increasing extreme weather events and driving sea-level rises.

Among the researchers’ findings was that a rise in sea levels approaching 2 metres by the end of this century ‘cannot be ruled out’, while the Arctic is likely to be ‘practically sea ice-free’ in September at least once before 2050.

Since 1970, global surface temperatures have risen faster than in any other 50-year period over the past 2,000 years, the authors said, while the past five years have been the hottest on record since 1850.

Scientists had expected temperatures to rise by 1.5C above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 but now believe it will happen between this year and 2040.

The 1.5C mark is considered to be the point where climate change becomes increasingly dangerous. The 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change committed countries to limiting warming to 1.5C but they have already risen by 1.2C.

The world’s largest ever report into climate change also said it was ‘unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, oceans and land’.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the new report a ‘code red for humanity’.

He warned: ‘The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.’

SEA LEVELS COULD RISE BY UP TO 4 FEET BY THE YEAR 2300

Global sea levels could rise as much as 1.2 metres (4 feet) by 2300 even if we meet the 2015 Paris climate goals, scientists have warned.

The long-term change will be driven by a thaw of ice from Greenland to Antarctica that is set to re-draw global coastlines.

Sea level rise threatens cities from Shanghai to London, to low-lying swathes of Florida or Bangladesh, and to entire nations such as the Maldives.

It is vital that we curb emissions as soon as possible to avoid an even greater rise, a German-led team of researchers said in a new report.

By 2300, the report projected that sea levels would gain by 0.7-1.2 metres, even if almost 200 nations fully meet goals under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Targets set by the accords include cutting greenhouse gas emissions to net zero in the second half of this century.

Ocean levels will rise inexorably because heat-trapping industrial gases already emitted will linger in the atmosphere, melting more ice, it said.

In addition, water naturally expands as it warms above four degrees Celsius (39.2°F).

Every five years of delay beyond 2020 in peaking global emissions would mean an extra 20 centimetres (8 inches) of sea level rise by 2300.

‘Sea level is often communicated as a really slow process that you can’t do much about … but the next 30 years really matter,’ said lead author Dr Matthias Mengel, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, in Potsdam, Germany.

None of the nearly 200 governments to sign the Paris Accords are on track to meet its pledges.

Advertisement

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-9911791/Unprecedented-rain-falls-Greenland-summit-time-1950.html