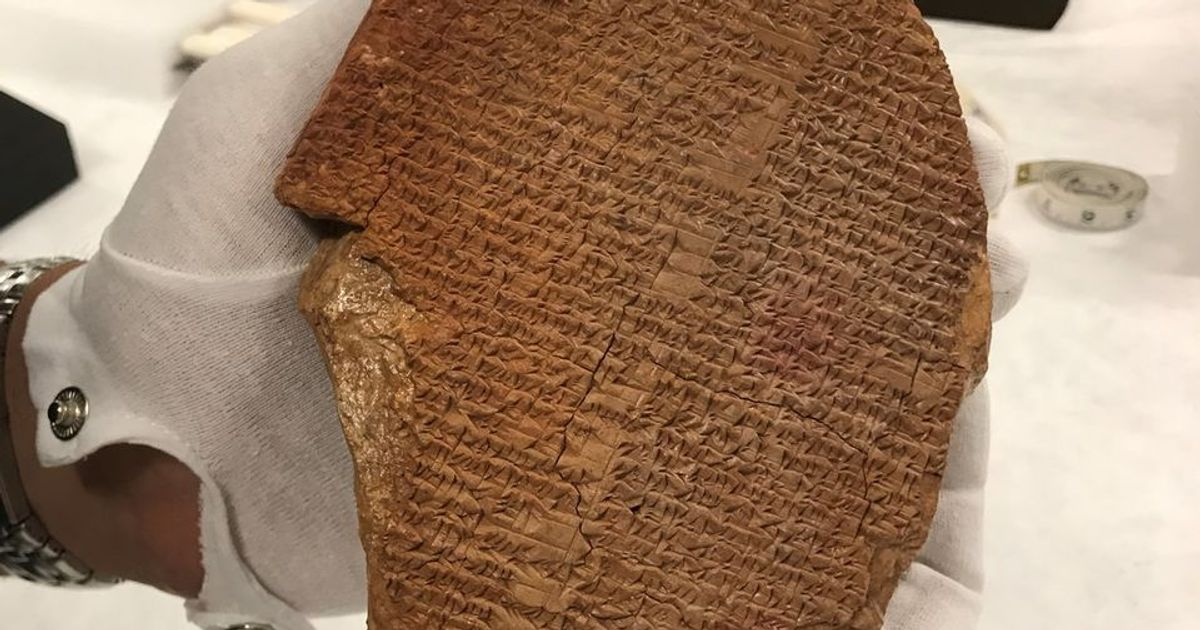

Much is happening in the global debate over the rightful place of cultural objects. Not a week goes by, it seems, without an important return being announced. Last week it was the return at a ceremony in Washington DC of the ancient Gilgamesh tablet, going back to Iraq after its seizure from Hobby Lobby by US authorities. Prior to that it was the return to Ethiopia of ten important artefacts looted by British troops during a punitive expedition in 1868. The end of August saw the restitution of over 100 artefacts to Pakistan by the New York District Attorney’s office, part of the haul confiscated from discredited antiquities dealer Subhash Kapoor and his Art of the Past gallery in Manhattan (nearly 500 of these pieces have been returned to 11 countries since the beginning of the year).

In addition to what’s happening in the antiquities market, governments themselves are taking strong stands on the matter of long-ago acquired artefacts, many of which are now held in public museums. Germany seems to be taking the lead. Along with a 2019 statement by federal government representatives and ministers from the 16 states on a rousing set of principles pertaining to cultural objects taken during colonial times, we have seen a series of repatriations to Namibia (the former German colony of South-West Africa) and the April announcement of the return of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, set to begin in 2022. The Netherlands and Belgium appear to be moving in a similar direction. And France at the end of 2020 passed a law to return 27 important cultural objects to Benin and Senegal, which should take place by the end of this year.

In many ways, it was French President Emmanuel Macron who got the ball rolling on the restitution discussion back in November 2017. During a speech in Burkina-Faso, he made an unexpected and unprecedented call for “temporary or permanent restitution” of African heritage from French institutions to Africa. This effectively put the global cultural sector on notice. Even if the subsequent commissioned report, penned by the academics Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, went largely unimplemented, it nevertheless helped to sharpen the focus on ‘restitution’: the return of cultural artefacts as a way of doing justice for past wrongs.

These developments reveal society’s growing sensitivity to historical injustices and, in the cultural context, to a greater awareness of the power structures at play when material was removed in the first place, especially when such removal was achieved through force of arms, clandestine excavation, corruption or outright theft. In the context of African restitution, this was given added impetuous by the Black Lives Matter protests and the ongoing debate over the removal of statues of controversial figures with links to slavery. In this respect, restitution may be seen as an attempt to make amends for the crimes of history.

But there is something else going on as well…

The restitution debate has afforded certain governments a new way of establishing themselves through diplomatic links and geopolitical influence, a particularly cultural form of ‘soft power’. Macron’s Burkina-Faso speech can be seen not merely as a way of doing good, but also as a way for France to reassert its validity in francophone Africa. Delivered six months after he became President, the speech offered the now-familiar Macron hallmarks: a break with the past, an eschewing of France’s role as colonial power in favour of international relations based upon partnership and economic mutual interest, and a hint of the executive diktat. The goal of expanding French spheres of influence is well served by an engagement with African countries around questions of restitution.

With a similar intent of gaining international influence, other powers are engaging with restitution in different ways. China, for example, has long sought to recover its own cultural artefacts that were looted or pilfered by European armies and adventurers during the country’s so-called ‘century of shame’ from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. An interest in restitution has emerged as a significant, though unexpected, feature of its Belt and Road Initiative, the massive programme of global infrastructure investment.

The impressive new museum in Dakar, Senegal that now holds restituted material from France? Paid for with €35m from China. It is perhaps no coincidence that Senegal was the first West African country to sign onto Belt and Road, which it did in 2018. And it should be added that the port of Dakar represents an essential deepwater transportation hub at the western tip of the continent.

When Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Greece in 2019, he declared himself a staunch ally in the cause of restituting the Parthenon Marbles from Britain. “Not only will you have my support,” he said in a statement, “we should work together. Because we have a lot of our own relics abroad, and we are trying as much as we can to bring these back home as soon as possible.” This was a diplomatically astute way of getting in with one’s hosts—not a bad manoeuvre when the Chinese-owned port of Piraeus is such a vital lynchpin to China’s trade with Europe.

As the returns of cultural objects continue—or multiply—we will see restitution emerge as more than simply a series of discrete and disconnected occurrences. Something much broader is happening, a reckoning of sorts with history. Countries, institutions, businesses and collectors can decide how they want to operate in this new landscape. Some will perhaps let the moment pass. While others will most definitely use it to their advantage.

Alexander Herman is assistant director of the Institute of Art and Law. His book on the topic Restitution: the Return of Cultural Artefacts (Lund Humphries) will be released on 30 September.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/restitution-what-s-really-going-on