In Just the Blink of an Eye, 2005, performance designed by Xu Zhen, Long March Space, Beijing.

In Just the Blink of an Eye, 2005, performance designed by Xu Zhen, Long March Space, Beijing.

How peculiar—in a good way—is Art & Trousers: Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art (University of Chicago, 2021) by veteran curator and museum director David Elliott? First of all, the combination memoir, essay collection, and cultural history covers areas little discussed in putatively “global contemporary” art history and criticism. Yes, Elliott devotes roughly a third of his pages to East Asian art stars like Cai Guo-Qiang and Ai Weiwei, as well as somewhat less familiar figures such as Japan’s Miwa Yanagi, Korea’s Yeesookyung, and China’s Xu Zhen. But the author also weighs in with both current cultural savvy and detailed historical knowledge on pan-Asian artists such as Pakistan’s Rashid Rana, the Philippines’ Rodel Tapaya, and Indonesia’s Heri Dono. He even covers young experimental practitioners in Tibet, some of whom (in a nod to local tradition) choose to remain anonymous, thus foregrounding their work rather than themselves.

Little wonder, then, that the book’s second strand is the story of Elliott’s own extraordinarily multicultural career. Since 1973, when he began as a regional officer for the Arts Council of Britain, Elliott has served as director of four museums in Europe and Asia; artistic director of biennials in Sydney, Kiev, Moscow, and Belgrade; and organizer of some of the era’s most revelatory regional-focus exhibitions. His expertise derives, in short, not from producing a string of theory-laden tomes for the academy, but from fifty years of direct interaction with Asian artists and artworks, curators and critics, scholars and collectors.

The narrative pace is bracing. Elliott takes readers with him through his chain-reaction discovery process, often noting the way seemingly random encounters lead to new realms of cultural experience. “Like in life, everything was jumbled up,” he says of the deliberate intermingling of traditional, folk, modern, and contemporary artworks in one of his early shows, “India: Myth and Reality” (1982). Preparations entailed travel to a dozen cities on the subcontinent. Two years later, Elliott’s chat with a British art historian leads him to a graduate student specializing in contemporary art from Japan, the young woman’s homeland. Exhibitions (and more fortuitous introductions) follow. Elliott’s burgeoning interest in manga leads him to Chinese comic books and then onward to avant-garde art throughout the People’s Republic. And so it goes, across five decades and countless national borders.

David Elliott, Art & Trousers: Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art, Hong Kong, Art Asia Pacific Foundation, 2021, distributed by University of Chicago Press; 368 page, 640 color illustrations, $56 paperback.

David Elliott, Art & Trousers: Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art, Hong Kong, Art Asia Pacific Foundation, 2021, distributed by University of Chicago Press; 368 page, 640 color illustrations, $56 paperback.

This constant ingenuity is echoed in Elliott’s cheeky book title and the unorthodox thesis it signals. Art and trousers? Who else would think of seeing the worldwide conversion to wearing pants over the past few centuries as a metaphor, or objective correlative, for the rampant spread of modernist principles—not only in art but in social relations, economics, science, and philosophy? (The book is a catalyst for fresh historical and sociological thought; it does not systematically study pants as an artistic motif, medium, or theme.) Elliott makes his argument in three newly written chapters interpolated among thirty-two previously published monographic essays. “The Slippered Pantaloon” introduces the notion of an “absurd” duality in the symbology of pants (funny vs. deadly serious); “Who Is Wearing the Trousers?” treats this garment as a marker of power; and “A Short History of the Trouser” sketches the evolution of pants from Paleolithic times to the present.

Elliott’s central thesis regarding Asian modernism—that trousers have been a sometimes oppressive, sometimes liberating signifier of Western influence—would surely be more compelling if he had expanded it to Western clothing in general. (This would circumvent as well the problem that traditional Asian cultures also had many kinds of pants.) Anyone can see at a glance that the Euro-American style of dress has pervaded Asia, especially since the mid-nineteenth century, and not vice versa. Yet the author opts to focus on pants specifically—in part, one suspects, for comic effect and memorability, and in part because of the long-standing association between pants-wearing and authority. Readers with a sporting nature will simply grant him his striking choice and his fun.

In many traditional Asian cultures, Elliott recounts, trousers were long viewed as the garb of foreign “barbarians” or, worse yet, of the indigenous laboring poor. No feudal Japanese daimyo, no gentleman scholar in Old China could possibly have foreseen (or abided the thought) that his descendants, male and female alike, would one day abandon their refined silk robes for the coarse two-legged denim of Wild West gold miners. Peter the Great’s 1701 Decree on Western Dress, outlawing all flowing Tatar regalia, hit his domain like a bomb. In isolation, such examples might seem ludicrous, but collectively, occurring at various times across the world’s largest and most populated continent, they represent the shattering and transformation of entire worldviews—and thus a radical overhaul of the very notion of being.

We have, Elliott observes, our own epochal precedents in the West, most notably the overthrow of effete aristocrats wearing knee breeches and silk stockings by the boisterous pantaloon-clad sansculottes of the French Revolution. Again and again, in both West and East, modern pants have been associated with mobility—both physical and social—energy, casualness, and egalitarianism. The formula holds for women even more than for men. Elliott compares the sartorial daring of a cross-dressing George Sand, bloomers-wearing suffragettes, and even Marlene Dietrich in her sultry androgynous mode, to the calculated defiance of the trousered anti-Qing Dynasty revolutionary Qiu Jin as well as Japanese moga (modern girls) strolling Ginza in voluminous “beach pajamas” around 1932. In each case, the immediate goal of this self-assertion was different, but the underlying drive toward equality was ubiquitous.

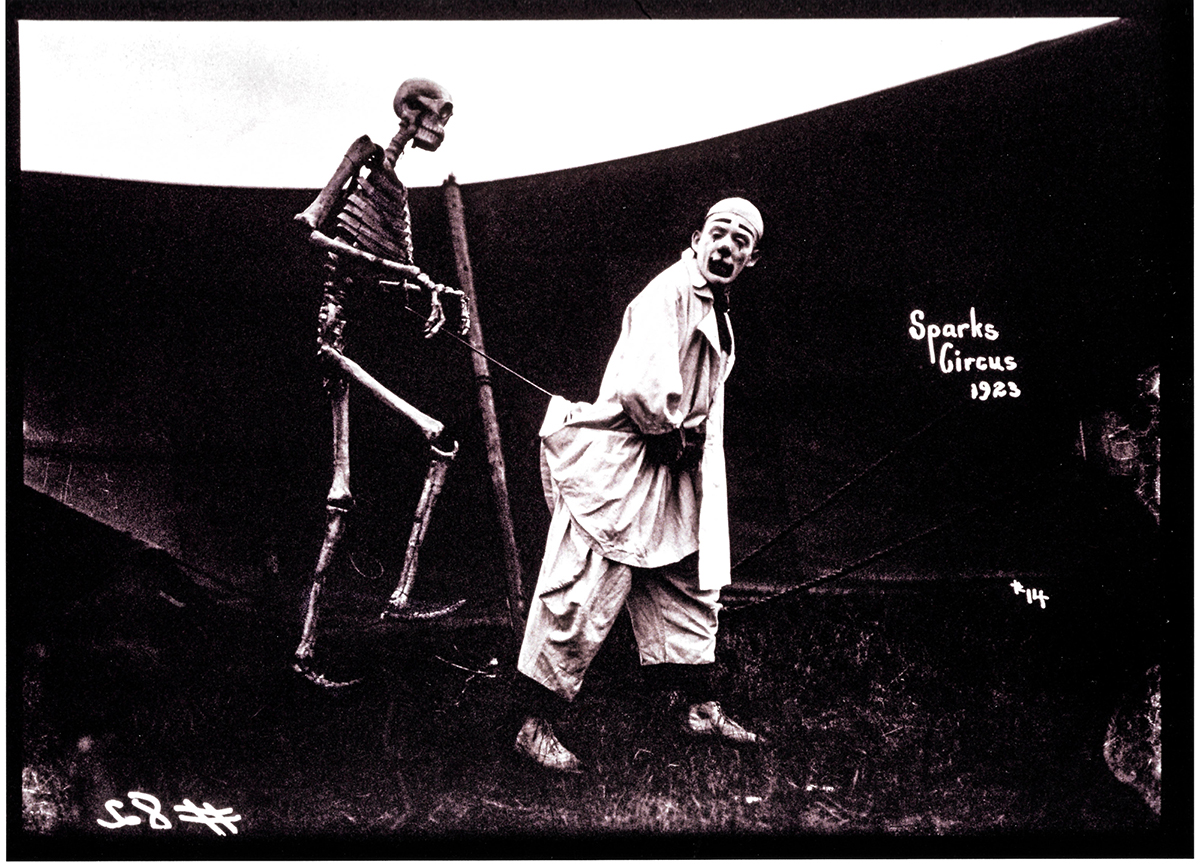

Frederick W. Glasier’s photo of a clown and a skeleton at the Sparks Circus, 1923.

Frederick W. Glasier’s photo of a clown and a skeleton at the Sparks Circus, 1923.

In this book brimming with 640 illustrations, both artistic and documentary, the frequency of clown imagery reflects not only the subversive effect of baggy-pants humor on old-school propriety (likewise the target of avant-garde art everywhere) but also Elliott’s own playfulness in assembling his wryly provocative art survey cum costume history. A sly jollity enlivens his references to gender travesty in traditional Asian theater, his tongue-in-cheek chapter on Thailand’s Chatchai Puipia (written, at the living artist’s urging, as though Chatchai were dead and being memorialized), and his use of surprising pants-related quotes from commentators including Marco Polo and Shakespeare.

None of this lessens the seriousness of Elliott’s analysis. He stresses, quite rightly, that trousers and modernity came to Asia through colonization:

“In the unseemly rush to foreclose markets, grab land, and fill vacuums, the trouser, an expression of righteous, dominating, male power at home, when worn by soldiers, merchants, bankers, colonialists, or missionaries abroad—rampaging, occupying, merchandising, ruling, converting, or just trading opium—again revealed its original barbarian status and began to be regarded by many not-so-willing victims and subjects as just yet another token of arrogant, ‘long-nosed’ Western imperialism.”

All terribly true. But, like most art world writers, Elliott leaves out—or passes lightly over—the other half of the story. He prefers instead to lament the loss of local traditions, rail against the evils of capitalism, and disparage his fellow Westerners as though we alone, of all the peoples of the earth, had ever practiced subjugation and butchery. (Tell that to the conquered souls who labored and died under the shoguns and samurai of precolonial Japan, the Manchu emperors of China, the khans of Central Asia, or the maharajas of India.)

There is, however, a vaudevillian black-box trick in the middle of Elliott’s historicocritical performance. For centuries, much of Asia, we’re told, was cast in colonial darkness; nothing but Western abuses and horrors went into the magical case. Yet today, presto chango, fantastic examples of social and artistic inventiveness spring up helter skelter in places like Shanghai, Mumbai, and Yogyakarta. Dazzled readers can only wonder how, after so much Western depredation, such great creative energy can possibly burst forth. India’s Jitish Kallat makes a stairway LED display of Swami Vivekananda’s 1893 address to the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Rasheed Araeen, from Pakistan, presents a performance in which a soundtrack alternating between Handel’s Messiah and Bollywood film show tunes accompanies images of exploited Asian workers in the UK. Xu Bing inscribes two breeding pigs with pseudo-English words (on the randy male) and fake Chinese characters (on the female) in a pointed mockery of transcultural insemination. Elliott is at pains to argue that this bold synergy arises when Asian artists incorporate, dispute, and modify Western influences, melding them with the myths, crafts, and arts—both courtly and vernacular—of their own ancient cultures.

True again. But, oddly, the curator who so legitimately prides himself on appreciating the “jumble” of artistic legacy and recent art practice gives scant attention to the benefits to the body politic, and to the human spirit, that came along with the new pants-wearing world order. Occasionally, he remarks on the galvanizing effect of exhibitions from abroad or notes that the most inventive Asian artists tend to be those who have spent time in places like New York, London, and Berlin. But having penned a well-founded tirade against colonialism, he offers no offsetting paragraph-length acknowledgment of Western social boons: free speech, rule of law, religious tolerance, empiricism, private property, secularism, entrepreneurship, industrialization, democracy, and perhaps greatest of all (because it’s most intimate) personal autonomy, the right to think and feel and act as an individual, without being instantly accountable to parents, clan members, in-laws, village councils, priests, neighbors, tribal elders, honored teachers, imperial officials, or maiden aunts.

Modern Girls strolling the swank Ginza district of Tokyo, ca. 1932.

Modern Girls strolling the swank Ginza district of Tokyo, ca. 1932.

No one would argue that such empowering modern mechanisms, from the scientific method to honest elections, now operate all at once and perfectly in Asia, any more than they do in the West. Lived history, as Art & Trousers repeatedly shows, is always a mishmash, riddled with stops and starts, contradictions, surges, and reversals—often awash in blood. But the very idea of these socioeconomic virtues, and of the free and self-determined life without which contemporary art would be inconceivable, was developed in the post-Enlightenment discourse of the West and sparked in the minds of colonized peoples by none other than their own oppressors.

People are paradoxical, and so is their history. That truism infuses what we might call the second-wave duality of the trousers revolution, prompting many Asian artists and critics to play the “hypocrisy” card. They can now routinely assail their own restrictive societies for a lack of Western-style liberalism (conceived by the likes of Locke, Rousseau, and Jefferson), and yet simultaneously—and validly—charge the West with failing to live up to its own shining ideals. Such is the complexity of cultural exchange, as amply documented, at least in the aesthetic realm, by Elliott’s challenging and admirably cosmopolitan study.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/david-elliott-trousers-modern-art-asia-1234604157