The 34th edition of the São Paulo Bienal draws its title, Faz escuro, mais eu canto (Though it’s dark, still I sing) from a verse in the poem Madrugada Camponesa (1962) by Thiago de Mello, in which the Amazonian poet sought to inspire optimism and perseverance amid the polarising years of the military dictatorship in Brazil. The theme is poignantly pertinent; the show opens on the heels of escalating ideological conflict in the country between supporters and opponents of the conservative president Jair Bolsonaro’s government, including clashing demonstrations between political parties that took place across Brazilian cities on Monday (7 September) during the celebration of Brazilian independence.

Themes around historical and present political and social tension resound throughout the show, which features more than 90 artists and 1,000 works. The main exhibition takes place in the Ciccillo Matarazzo pavilion in Ibirapuera park, where the biennial has been held since its fourth edition in 1957, with satellite exhibitions in 25 other institutions.

Visitors entering the pavilion first encounter a video from the São Paulo tourism board, run by the secretary of culture Mário Frias, a former telenovela actor who was appointed to the role by Bolsonaro last year. Then there is a meteorite that was unearthed from the rubble of the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, one of the few artefacts that survived the 2018 electrical fire that gutted the gravely underfunded museum. The unintentional juxtaposition between the historic object and the Bolsonaro government, which has significantly slashed arts budgets, underpins the bleak state of the Brazilian cultural sector while also sending a message of resilience.

Drawing parallels between the past and present was central to the curatorial framework of the biennial, according to the chief curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, who organised the exhibition with the adjunct curator Paulo Miyada and guest curators Francesco Stocchi and Ruth Estévez.

In an installation conceived for the exhibition, the Brazilian photographer Mauro Restiffe combines a series of images of Bolsonaro’s inauguration with others from the 2003 inauguration of the hugely popular left-leaning former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—who was later imprisoned and eventually cleared of corruption charges—which were shown in the 2006 edition of the São Paulo Bienal. Through the strikingly similar scenes, Restiffe underscores how little things have actually changed through two very different incarnations of Brazilian politics. Andrea Fraser’s Reporting Live from São Paulo, I’m from the United States (1998)—a multi-channel video performance in which the artist pretends to be a television reporter covering the 24th São Paulo Bienal for TV Cultura—also reflects on the long-lasting economic crisis and its effects on cultural production in the country.

Among other significant works are Barril, Presunto and A Carga (all 1969) by the Brazilian artist Carmela Gross, which were exhibited at the 10th São Paulo Bienal in 1969. That edition became known as the “Boycott Biennial”, because many artists refused to participate as a protest against the dictatorship. The set of sculptures, all covered by shroud-like tarps, reference the censorship and violence instituted by the military regime at the time, and draw comparisons to moves made by the present government to control federally funded cultural projects.

There are also several sculptures installed throughout Ibirapuera park, including a monolithic work by Paulo Nazareth honouring Marielle Franco, the Rio de Janeiro city council member and political activist who was assassinated in 2018.

The biennial features also its most comprehensive presentation of works by Indigenous artists, coinciding with the largest-ever Indigenous-led protests last month in Brasília against the Bolsonaro administration, which has worked to lessen environmental protection of the Amazon and demarcate land held by Indigenous communities.

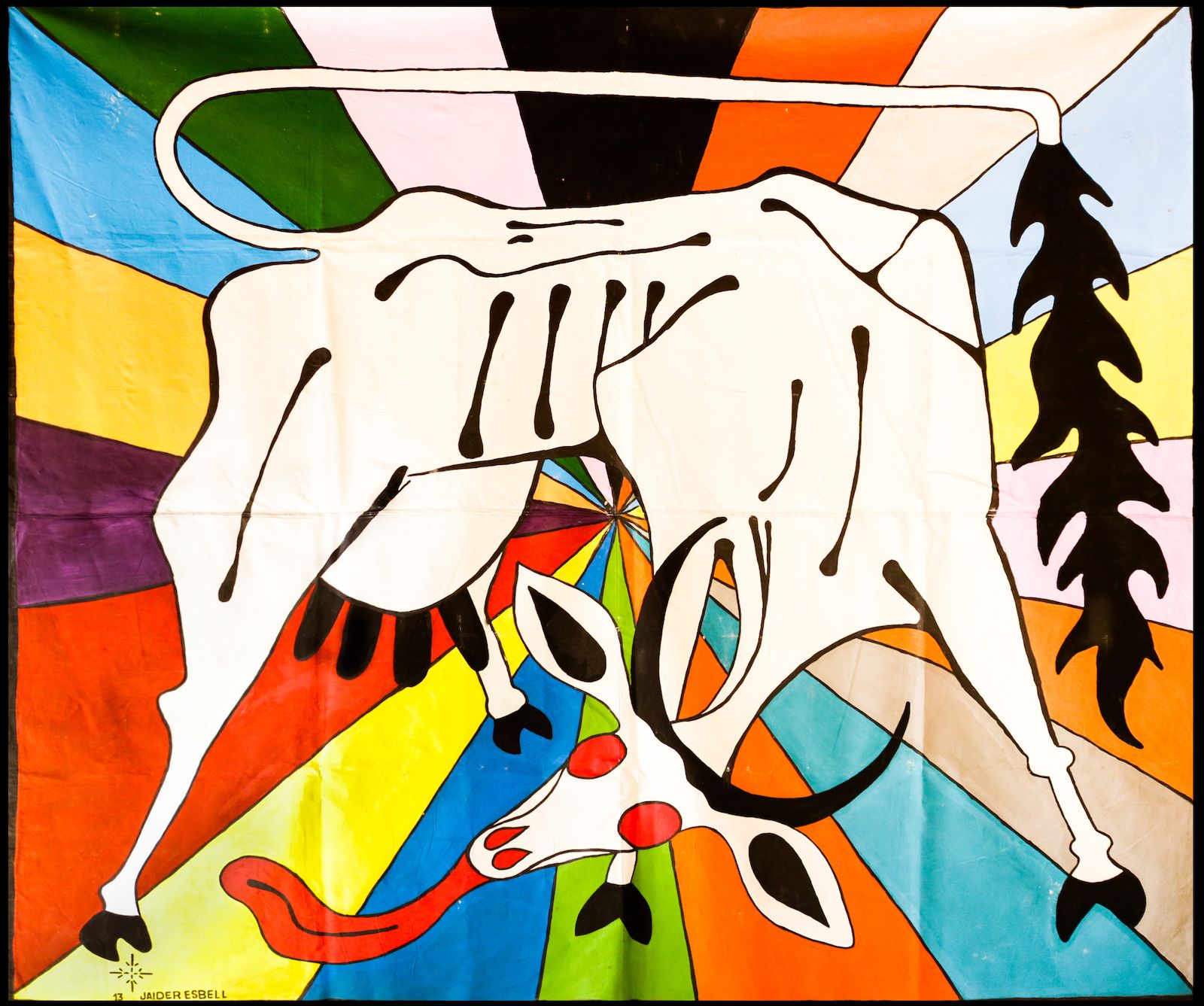

Satellite exhibitions also champion Indigenous histories: the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo is holding a survey of contemporary Indigenous art titled Moquém Surarî: Arte Indígena Contemporânea (until 28 November) that includes works by more than 30 Brazilian artists. “After this museum, there’s a park, then there’s a polluted city and then we get to Brasília, where there are people—without calling anyone a criminal—working with forces that are against harmony,” says the curator and artist Jaider Esbell, a member of the Macuxi people. “It’s important that an art exhibition shows that we are alive, and that our culture is not theatrics or something from another world.”

There is also a strong focus on Afro-Brazilian histories. Along with a presentation in the main exhibition, the Instituto Tomie Ohtake has opened an engrossing retrospective (until 28 November) devoted to the illustrious work and life of the late French photographer and anthropologist Pierre Verger, who captured some of the earliest photographs of the Candomblé religion. Verger discovered the Afro-Brazilian religion when he arrived in Salvador in the late 1940s and travelled to Benin in 1953 to become an initiate. For more than six decades, he chronicled how Candomblé was practiced both within Brazil and Africa, and captured what would later become ubiquitous images of the religion, helping legitimise a practice that has long faced prejudice and persecution by the Evangelical and Catholic churches in Brazil.

The São Paulo Bienal, which celebrates its 70th anniversary this year, is the longest-running international exhibition after the Venice Biennale. It has received a boost in budget this year, estimated at $14m (R$73m), allowing it to create its largest show to date. The event opened in a staggered format due to the pandemic, with the introductory show Vento and other projects launched in November last year.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/review/sao-paulo-bienal-echoes-the-political-polarisation-in-brazil