The Tate’s “Gauguin” painting Tahitians has been downgraded as a fake. It is excluded from the authoritative catalogue raisonné of Gauguin’s work, which has just been published by the New York-based Wildenstein Plattner Institute. Although the Tate still accepts the painting as authentic, a spokesman says that it will now “keep the work under review”.

Tahitians was acquired in 1917 from Roger Fry, the distinguished art historian who invented the term Post-Impressionism. Its absence from the new catalogue raisonné was spotted by Fabrice Fourmanoir, a former Polynesian resident, Gauguin enthusiast and now a researcher on authenticity of his works.

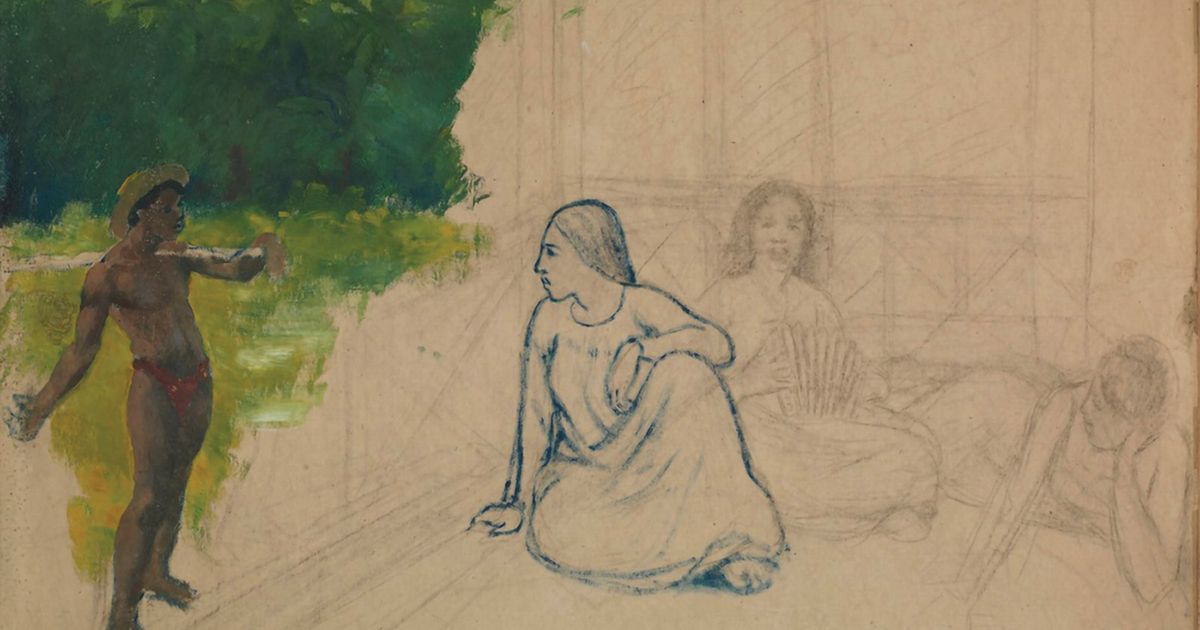

Tahitians is an unusual picture, since it is partly painted with oil on paper, which has been mounted on canvas. On the left side of the composition, a Tahitian boy and a section of landscape with palm trees and mountains are roughly painted in oils. Three women are inside a hut or veranda, their outlines sketched in charcoal. The woman in the centre of the composition is more firmly drawn in blue crayon.

The fact that the painting is unfinished gives it a special importance. If authentic, it would reveal a considerable amount about Gauguin’s technique—starting with a rough charcoal sketch, firming in the outlines and then painting in oils. But if it is a fake, it is misleading.

Reasons not revealed

The decision to exclude the unsigned Tahitians from the catalogue raisonné was made by its two leading committee members: Richard Brettell (who died in July 2020) and Sylvie Crussard, who had worked together for 20 years. The institute is withholding the reasons for the rejection, to “maintain the confidentiality” of deliberations.

The first recorded owner of the Tate painting was the Druet gallery in Paris, which offered it on loan to Fry’s Post-Impressionism exhibition in December 1910. Fry bought it a few months later, probably for about £30. Fry believed it was a genuine Gauguin, although this was at a time when much less was known about the artist’s oeuvre.

Maker of myth

Fry was the committee secretary of the Contemporary Art Society, which he helped establish in 1910. He apparently sold the painting to the society, presumably for the sum he had paid.

In 1917 the society presented the picture to the Tate (then known as the National Gallery Millbank and administered by the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square). That year the Millbank gallery began to collect Modern foreign art—hence the Gauguin acquisition.

Since 1917 Tate has always regarded Tahitians as authentic. In 2010 it was included in Tate Modern’s exhibition Gauguin: Maker of Myth, although it was not shown when the exhibition travelled to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Belinda Thomson, the Tate’s external curator, says she is “surprised” that the picture is now excluded from the catalogue raisonné.

The subject matter of Tahitians bears some similarities to two other Gauguins: The Siesta (1892-94, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), showing four Tahitian women reclining in a hut or veranda, and On the Banks of the River at Martinique (1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), portraying a boy and seated woman looking at each other. These two examples could be used to adduce authenticity (on the grounds that the figures represent a Gauguin theme) or the reverse (with a faker imitating authentic works).

Fourmanoir is convinced that the Tate work is a fake. “It is a stereotypical colonial Tahiti scene, whereas Gauguin was looking for more primitive compositions. The poses, dresses and even the European accordion held by the woman show Tahitians ‘corrupted’ by European customs,” he says.

Polynesian pastiche

Polynesian pastiche

According to Fourmanoir, the Tate picture must have been painted by Charles Alfred Le Moine, who lived in Polynesia from 1902 (the year before Gauguin’s death) until 1918, the year of his own death.

Fourmanoir once owned 15 works by Le Moine, so knows his work well. “The poses, the dress and the man carrying bananas are very typical,” he says. Fourmanoir believes that someone coming from France to search for paintings soon after Gauguin’s death commissioned Le Moine to make a pastiche, which was then sold to Druet.

The Tate dates the painting to around 1891, very soon after Gauguin’s arrival in Tahiti. Its curators suggest it is an early study, “in order to come to terms with his new subject matter”. Importantly, the painting was accepted in the 1964 Wildenstein catalogue raisonné (a predecessor to the institute’s web publication), although at that point it was dated to 1894, during Gauguin’s two-year return to France.

A Tate spokesman says: “The work was included by the Wildenstein Institute in their Gauguin catalogue raisonné in 1964 and Tate was not contacted prior to the publication of the latest edition. We recognise there has been ongoing research into Gauguin’s work in recent years, so we will keep the work under review and retain an open mind about any research that might help cast familiar works in a new light.”

The Tate has two fully authenticated Gauguins: a Brittany landscape, Harvest: Le Pouldu (1890), and an important Tahitian painting, Faa Iheihe (1898).

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/tate-s-tahitian-gauguin-is-suspected-fake