• Read more about the Art Fund Museum of the Year Award 2021 here

A mile and a half out of Leeds city centre, the Thackray Museum of Medicine sits on the campus of one of Europe’s biggest teaching hospitals. Having begun life as the archive of a leading local medical supply business, the museum opened in 1997 in the former Leeds Union Workhouse building, which housed hundreds of the city’s poor and homeless in the Victorian era and served as a military hospital during the First World War. It is an evocative site for a museum that traces the rise of modern medicine and healthcare.

The Thackray brought that history straight into the present last December, when it hosted one of the world’s first mass Covid-19 vaccination hubs. Over five months, some 50,000 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine were administered to frontline NHS and care workers in the museum’s hastily repurposed conference centre. It has also hosted clinics for 5,000 volunteers taking part in the UK’s Novavax trials.

Coming at the end of a tough year of pandemic lockdowns—which forced the Thackray to delay completion of its £4.2m redevelopment until this May—the pop-up vaccine hub is “the thing we’re most proud of”, says the museum’s chief executive, Nat Edwards. He recalls receiving an email from the local NHS trust “on a Saturday night or Sunday morning” seeking a location close to the ultra-cold freezers needed to store the vials of Pfizer-BioNTech. The museum immediately stepped in and “by the Thursday, we’d received the first delivery of vaccine”, Edwards says.

An empty vial used on site has now joined the more than 70,000 medical items held in the collection. It is part of the museum’s drive to document Covid-19 history in the making, with new acquisitions such as DIY scrubs and a face mask—made during the early shortages of protective equipment—and a “Thank you NHS” rainbow t-shirt. Edwards anticipates that the current small display will be augmented with future exhibits and programmes around the pandemic: “It’s just thrown up so many ethical issues and good hot topics to discuss.”

What is more, a global public health emergency—and the accompanying spread of misinformation—shows up the fundamental importance of medical museums, Edwards believes. “I’d hope that something like this would get us to take our medical history more seriously and see the value of it,” he says, noting that the UK has no national museum dedicated to the subject, even while it has multiple institutions relating to “war in one form or another, or the spoils of war”.

Though the revamp was designed before Covid-19 struck, the galleries are full of details that resonate with our pandemic age, from the power of hand-washing in preventing disease to the life-saving vaccination campaigns of decades past. The displays are eclectic, beginning on the ground floor with a grim recreation of life in the slums of Victorian Leeds—a popular feature of the old design that went largely unchanged. Highlights upstairs include an affecting film portrait of Chris King, who in 2016 underwent the UK’s first double hand transplant at Leeds General Infirmary; a frank and funny sexual health clinic; and what Edwards calls the “best collection anywhere of English apothecary jars”.

The biggest transformation, Edwards says, has been a narrative shift away from the “greats of medical history” to emphasise the collective efforts of research and activism behind the textbook breakthroughs. He recently took pains to answer one visitor’s complaint that the Thackray was being “a bit woke” and “cancelling” the canon. “I don’t think we’re trying to cancel anybody,” he says. “We actually celebrate Fleming and Pasteur and all those people as heroes, as they should be.” Rather, the intention is to help visitors to “see themselves” in the onward march of medicine. “Because you won’t always see yourself in the story of the great Victorian surgeon. Or it’s quite a leap, isn’t it?”

To this end, the museum involved 200 people from local groups in co-producing the new displays. Their input is striking in the Normal + Me gallery, which breaks down the stigma and stereotypes attached to everything from premature babies to the menopause to LGBTQI+ experiences. Even the curating feels egalitarian, with Queen Victoria’s engraved silver hearing aid sharing space with the personal accounts of D/deaf and disabled people today.

This collaborative process helped to fill the “gaps” in the exhibits, Edwards says, but he stresses that community curating is less “an end in itself” than a way to build ongoing relationships. “It’s actually what happens next and what the community does with it that’s more important.” It soon became clear, for instance, that the museum lacked dedicated spaces for groups to work, resulting in the creation of a suite of rooms back of house. “We’ve ended up with a new resource which will actually be a lot more meaningful for people,” Edwards says.

It is fitting, then, that the Thackray hopes to spend the Museum of the Year prize money on “something utilitarian, but beautiful, that the community can use” outside its imposing building in the hospital grounds. Edwards imagines “some sort of really good play installation that we work with local schools to create, so that they can feel ownership of it every time they walk down the road”.

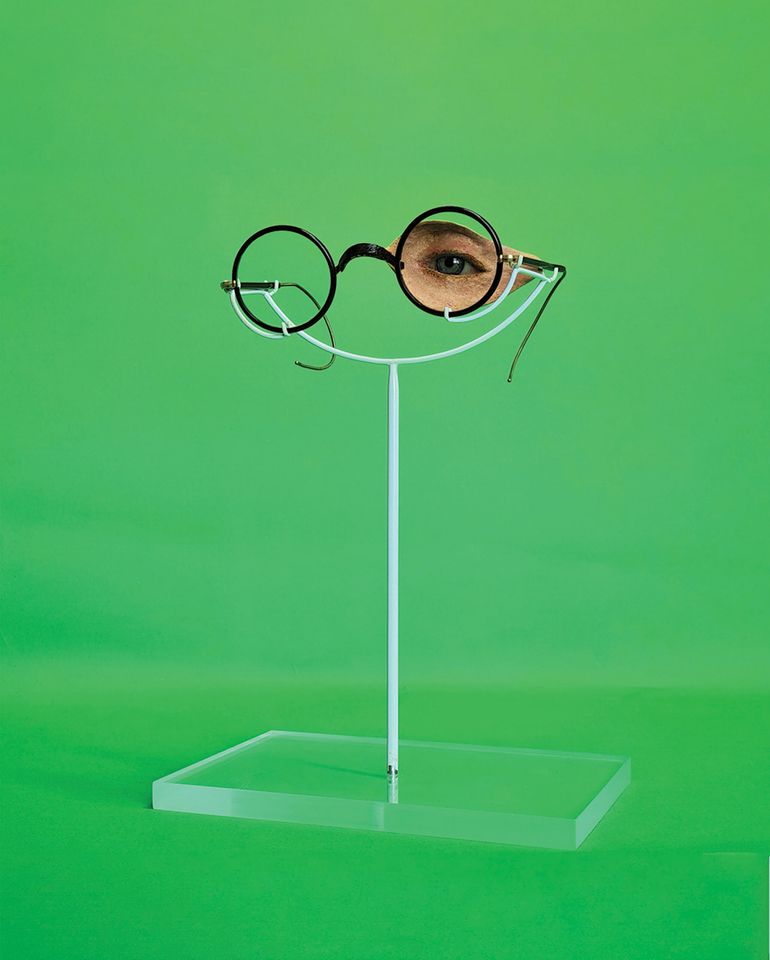

Must-see show at Thackray Museum of Medicine, according to its chief executive, Nat Edwards: Spectacles with facial prosthesis

Must-see show at Thackray Museum of Medicine, according to its chief executive, Nat Edwards: Spectacles with facial prosthesis

“This set of spectacles with an integral facial prosthesis was created by the artist Francis Derwent Wood when he was leading a team of surgeons and artists at the Third London General Hospital during the First World War in the Masks for Facial Disfigurement unit. Created with both clinical and sculptural skill and finished in situ on the patient by artists working to match colouring, these prosthetics are remarkable works of art. They evoke not only the horrific stories of facial trauma experienced by soldiers during the war but also the remarkable creativity that helped those soldiers to re-establish their lives. For me, this object sums up everything that’s brilliant about our collection. It’s redolent with a deeply personal human story. It represents medicine as a collaboration between different disciplines. It’s something that demands a second look—and when you make the effort to look closer it’s hard to look away.”

• Read about the other shortlisted museums here

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/feature/thackray-museum-of-medicine-history-in-the-making