When the call from Downing Street comes, there are few jobs an ambitious politician wants less than secretary of state for culture. The Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport is the Dignitas of British politics, a place to enjoy exhibition openings and cup finals before you quietly end your ministerial career. Only five out of 17 who have held the post have been promoted to a bigger government job.

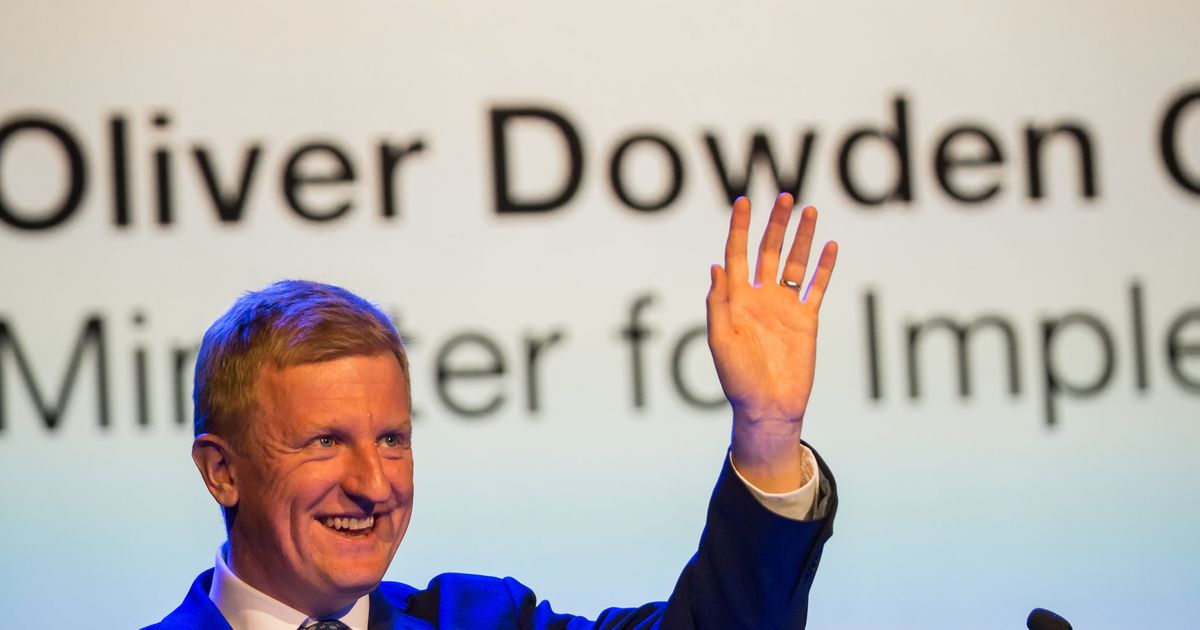

However, the current culture secretary, Oliver Dowden, in post for 15 months, is already tipped for promotion in Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s next cabinet reshuffle. An able communicator, Dowden has enthusiastically used his department to wade into Britain’s culture wars, providing eye-catching political cover for a government frequently beset by controversy and chaos. Dowden has won praise from the Tory press for defending contested statues, attacking institutions that “do Britain down” and seeing off the European Super League. Add in his role in securing a £1.87bn support fund for culture during the pandemic, and one could claim him as the most consequential culture secretary of the past decade.

But Dowden’s political wins have come at a price for the cultural sector. Thanks to his repeated interventions, the arms-length principle, through which government drew the benefits of supporting cultural institutions without the responsibility of running them, is dead. In July last year he instructed museums to “take as commercially minded an approach as possible” if they wanted to be sure of future government support. In September he threatened to withdraw funding from institutions that removed from display objects which, in light of the Black Lives Matter movement, were now regarded as offensive, such as memorials honouring slave traders. And at a meeting of national museum directors in February, he announced new policies to govern how museums present British history. His most chilling intervention requires museum trustees to sign a document supporting the government’s “retain and explain” policy.

British museums have never faced such an assault on their intellectual and operational independence. By contrast, King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands recently opened an exhibition at the Rijksmuseum exploring how the Dutch Golden Age was built on slavery. It is impossible to imagine a similar exhibition at the British Museum, opened by the Queen. Dowden must know that museums are now too weak, and too poor, to challenge his vision of our island story.

Let me look for silver linings. Tory governments have a troubled relationship with the arts, wary of being seen as elites enjoying elitist activities, and consistently cutting funding. But Johnson’s populist government wants to wrap everything it does in a Union flag and under Dowden has seen how culture can help it do that. His claim that the “Conservatives are the party of culture” will ring hollow to musicians who can no longer tour in Europe or students faced with cuts to arts education. Yet no previous Conservative culture secretary has ever made such a claim. Cultural institutions will find out whether it is better to be ignored by Johnson’s government, or embraced by it. The latter must mean at least some extra funding. But the future integrity of our cultural sector will depend on whether institutions are able to stand up to the culture secretary—whoever the next one is.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/dowden-culture-war-lieutenant