Pages from The Box Catalogues of the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach 1967-78 (2021), edited by Susanne Rennert and Susanne Titz.

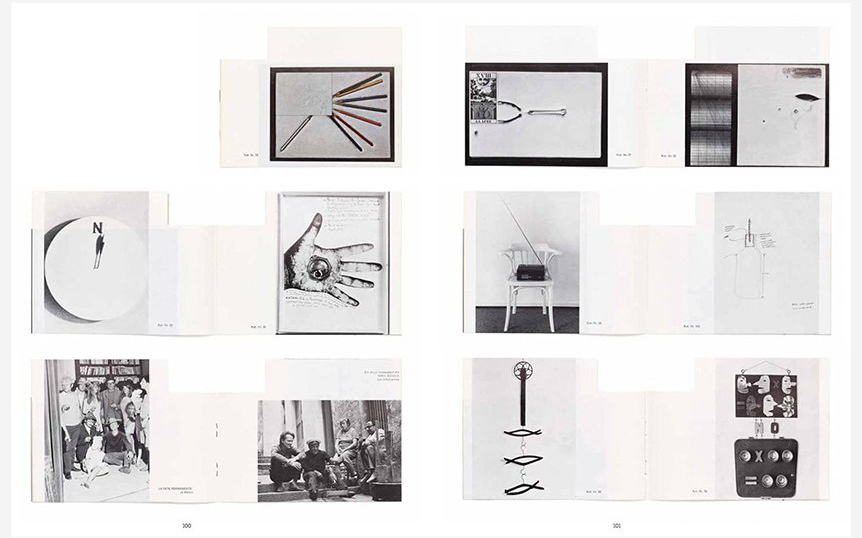

Pages from The Box Catalogues of the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach 1967-78 (2021), edited by Susanne Rennert and Susanne Titz.

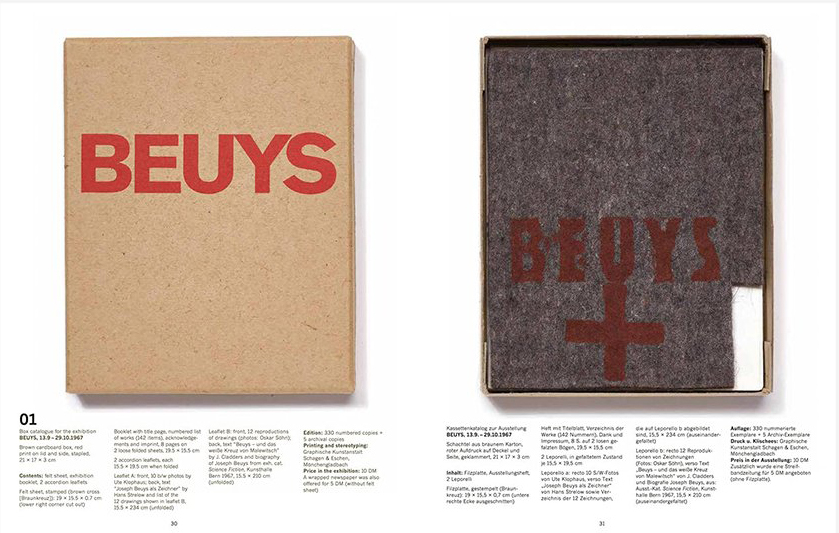

From 1967 to 1978, the curator and artist Johannes Cladders (1924–2009) organized a series of thirty-five shows intended to explore and expand the relationship between institutions and audiences at the small municipal museum in Mönchengladbach, West Germany, an unassuming city near the Dutch border. Cladders’s first show, in September 1967, featured a then-unknown artist named Joseph Beuys, a forty-six-year-old war veteran who had not previously been the subject of a major exhibition. He created an installation that served as a symbolic standard-bearer for Cladders’s ambitions. The relic-like objects Beuys placed in vitrines or rested casually against the floors and walls of the museum’s galleries announced that the new program of the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach would redefine the ways in which museums displayed artworks and interacted with publics.

Cladders went on to feature such artists as Bernd and Hilla Becher, Marcel Broodthaers, Hanne Darboven, Jasper Johns, Gerhard Richter, and Lawrence Weiner, among numerous others. Not content merely to organize shows of some of the most progressive and intelligent responses to modernism of the Cold War period, Cladders additionally produced experimental catalogues for each exhibition. These were limited-edition boxes, or Kassettenkataloge, which took the place of the usual book or pamphlet. The boxes might contain objects, meaning that members of the public were able to purchase physical pieces of art. This was an important intervention given that most residents of the city and the surrounding region were unfamiliar with contemporary art, if not openly hostile to the critical interventions of Conceptualism and Fluxus. With this publication strategy, Cladders at once appealed to the acquisitive logic of capitalism and democratized some of the most challenging art of his time.

Cladders’s catalogues were the subject of a 2018 exhibition at the Museum Abteiberg, a Hans Hollein-designed structure which since 1982 has housed the former Mönchengladbach Städtisches Museum. The show, “From Then On: Rooms, Works, and Recollections of the Anti-Museum 1967–1978,” has now been reconceived, in an appropriately “meta” gesture, as a sumptuous catalogue of unconventional catalogues bound in the form of a more traditional book, Die Kassettenkataloge des Städischen Museums Mönchengladbach 1967–1978 (The Box Catalogues of the Städischen Museum Mönchengladbach 1967–1978), edited by Susanne Rennert and Susanne Titz and published in July by the Museum Abteiberg and König Books. This catalogue of catalogues permits the reader to assess Cladders’s legacy, and to study an innovative publishing program undertaken with a modest budget in an unlikely setting.

Pages from The Box Catalogues of the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach 1967-78 (2021), edited by Susanne Rennert and Susanne Titz.

Pages from The Box Catalogues of the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach 1967-78 (2021), edited by Susanne Rennert and Susanne Titz.

Cladders is probably best known today for coining the term “anti-museum.” In a 1968 essay, “Das Antimuseum: Gedanken zur Kunstpflege” (The Anti-Museum: Thoughts on Curation), Cladders lays out his radical reflections on art and institutions. He writes, “The concept of ‘anti’ in anti-museum should be understood as the demolition of the physical walls and the building up of a spiritual house.” No simple negation of the noun museum, Cladders’s use of the oppositional prefix anti- was intended to call attention to the positive, generative, collaborative, and informal relationships that might exist between artists and institutions, especially when art is envisioned as something to be removed from the confines of the museum.

Rennert and Titz have done extraordinary justice to Cladders’s curatorial convictions, particulary to his material manifestations thereof. Their catalogue of the thirty-five box-catalogues photographically reproduces each of the boxes’ enclosures, which are usually cardboard, along with flawless images of the boxes’ interiors and contents (pamphlets, loose color plates, unexpected objects—such as an artificial rose in the box published on the occasion of Jasper Johns’s 1971 exhibition). The reproductions of pamphlets and other print materials are printed slightly shy of actual size, but it is always possible to read the writing included.

The reader may, for example, turn to box number six, the catalogue that accompanied Hanne Darboven’s 1968 exhibition. This white laminated cardboard box was printed with an enlargement of Darboven’s distinctive handwriting. It contained a booklet with information about the exhibition—the artist’s first at a museum—along with two short essays by Cladders, six cards reproducing Darboven’s mathematical calculations, and a blank graph-paper notebook, possibly to be used by the recipient of the box catalogue for their own calculations. For those interested in Darboven’s early career, this is an invaluable resource, a sort of treasure trove; Cladders’s lucid writing on her work and explanation of her eccentric arithmetic provided a crucial introduction to her methods and goals. His text holds up today, even after so much ink has been spilled in the elucidation of Darboven’s concepts and constructions. Similarly, Cladders’s early 1968 institutional presentation of the Bechers’ celebrated photographs of industrial architecture helped establish them as “conceptual photographers.” The box associated with this exhibition contained ten original silver gelatin prints along with a curatorial text. Although the show, with its meticulous documentary dryness, was presumably not to everyone’s taste, how amazing it must have been for some to be able to view the photography on display and then bring home this beautiful print object including actual photographs.

The visitor to the “anti-museum” imagined by Cladders was thus more than a passive viewer: they were a reader, a potential collector and curator, a possible critic, a presumed ally of experimentation, someone who could be trusted to take care of art. While it seems that many of the reasonably priced boxes—they ranged from 3 to 47 DM, which is roughly $60–$900, adjusted for inflation—were snapped up by art dealers, certainly some made their way into the homes of average citizens, a wonderful consequence of this state-sponsored initiative. Echoing the ethos of contemporaneous projects like magazine-in-a-box Aspen, Cladders’s vision was of art certified not by the institution, but rather by those who came to see it, who should necessarily have the chance to interact with it on intimate terms and carry it back with them into their everyday lives.

Die Kassettenkataloge des Städischen Museums Mönchengladbach 1967–1978 is thus an occasion for readers to reflect on the remote access efforts of today’s museums, which can seem ineffective and unimaginative in comparison to Cladders’s generous offerings. While the publication has at least one glaring oversight—lack of English translations of any of the original German-language box-catalogue texts, which are among the most historically significant aspects of the catalogues—it remains visually stunning, and Rennert and Titz provide useful essays. At a time when many are attempting to re-think the role and responsibilities of museums in civic and national life, given their rootedness in nineteenth-century colonialism and plunder, as well as their dependence on a frequently exploitative donor class, Cladders seems at once ahead of and behind the game: while he confined himself somewhat obsessively to a particular artistic niche and mainly exhibited the work of white European men, he was vigorously engaged in combatting anti-intellectualism and fear of the strange and new. His primary tools in this struggle? Cheap print materials, excellent design, and a sense of humor.

This story is the latest in Lucy Ives’s column on artists’ books.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/box-catalogues-monchengladbach-cladders-1234600798