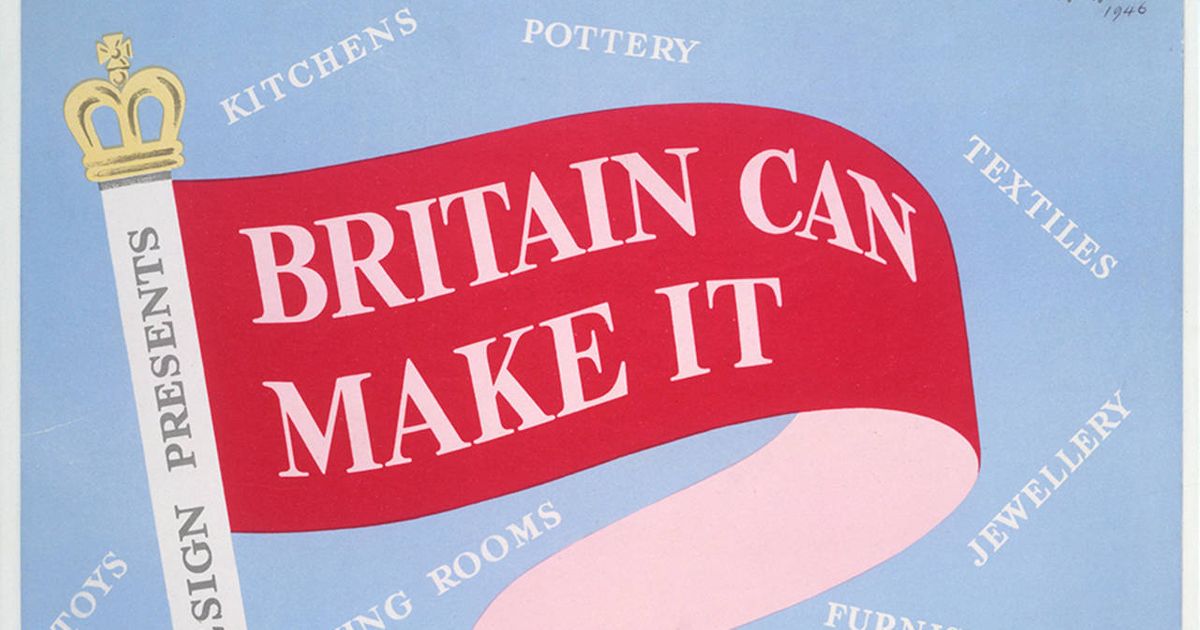

This September marks the 75th anniversary of the V&A’s post-war exhibition, Britain Can Make It, the 1946 display geared up to showcase the future of the country’s design and promote its role in the recovery of the nation’s economy.

Presented by the government’s recently formed Council of Industrial Design, the adjoining catalogue hailed industry’s “rapid changeover from war to peace production” and pulled together experts from multiple fields of industry to explore how design could add edge to British products.

Preceding the Festival of Britain of 1951, the national exhibition and fair which enjoys its 70th anniversary this summer, it is little wonder that 1.5 million visitors, worn down by the drudgery of war and rationing (a weariness perhaps more conceivable in our post-lockdown society), were enthralled by the glimpse of what a future Britain could look like.

“I’ve been involved in multiple anniversaries analysing this exhibition, but there is something very significant about the themes it raises in light of Britain’s outlook today,” says Jonathan Woodham, emeritus professor of design history, University of Brighton, who has published widely on the exhibition.

So, what can a post-pandemic, post-Brexit, climate-change-pressured Britain learn from such a historic moment?

International relations

The exhibition was clear in its prioritisation of design as a means to further the country’s international position. Indeed, the press soon mocked the show’s title, claiming “Britain Can’t Buy It” when it came to enjoying products created with foreign markets in mind.

Post-Brexit Britain faces a comparable need to re-establish its international trade relations, with additional challenges facing manufacturing as a result of additional trading costs.

“We need to send the message that our country is open and responsive,” says Caroline Norbury, chief executive of the Creative Industries Federation. “We had a very enviable position in our soft power and I fear we’ve been so fixated on domestic problems that we took our eye off the ball internationally and painted the picture of a divided nation.”

She adds: “Our engagement with creative industry leaders over the past 18 months has demonstrated their desire to address past inequalities, commit to sustainable and inclusive growth and use the power of creativity to design solutions to many of our country’s economic and social challenges.”

Appreciation of the creative sector

If the 1946 British Government demonstrated a commitment to the creative sector by staging the exhibition, the recent £1.57bn Cultural Recovery Fund arguably testifies to a belief in the sector’s role in Britain’s post-pandemic recovery. Similarly, the government’s Plan for Growth, announced in March, makes particular mention of creative industries.

However, such support is undermined by an apparent resistance to prioritising the arts in education, including the plans to cut higher education funding to arts subjects by 50%, announced this May.

“There seems to be less understanding of the importance of cultural subjects in the curriculum and confusion over the idea that such investment is about creating professional ‘artists’ or ‘designers’, rather than nurturing a core set of problem-solving skills which translate across multiple career paths,” says Ben Evans, director of London Design Festival, which launches its 19th edition this month (18-26 September).

He adds that the sector is designed on talent migration; “If I think about the greatest design stars in London, almost all of them don’t have a British passport. We’re closing door to the next generation of talent and I’m very mindful that the pendulum is swinging away from Britain.”

Priorities

One area where there has been an astonishing shift since the 1946 exhibition is in the social problems society asks design to solve. Primarily, in terms of sustainability and consumption.

Whereas post-war society was little concerned with the planet’s diminishing resources in its celebration of new materials suited to mass consumption (notably plastics and aluminium) today, there is little design which doesn’t have “sustainability at heart”, says Evans.

If the optimism of the 1946 exhibition teaches us anything, it is perhaps the value of harnessing public spirit and promoting a moment of collaboration. As Norbury notes of the recent pandemic, “it did convene a lot of creativity—I hope we can now come together to design a better future.”

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/v-and-a-exhibition-75-years-later-britain-can-make-it-design-anniversary