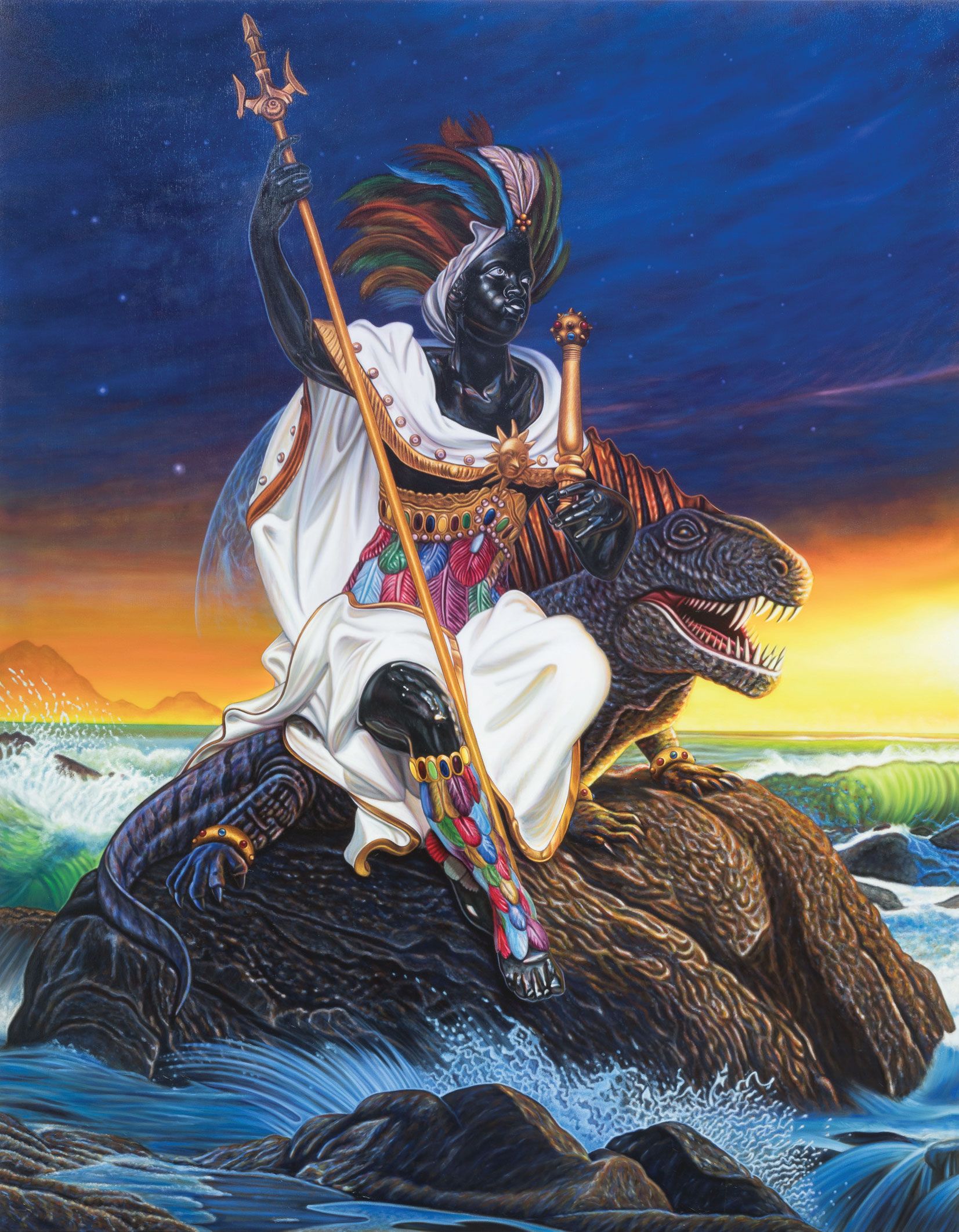

“I hope what the section does is show the complex nature of how each of us might envision the future,” says Wassan Al-Khudhairi, the curator of the Focus section at this year’s Armory Show. “The works are informed more by the idea of looking into the future as a place to start rather than making work ‘about the future’.” Works are often interdisciplinary, the curator says, and engage in notions of cross-cultural collaboration, environmental stewardship, mutualism, care and the power of communities coming together. Al-Khudhairi says she wants to “create a space that captures the ideas of a group of artists that consider the future in the context of our current conditions”. For example, a solo presentation by the Crow Nation artist Wendy Red Star entitled A Float for the Future, with the New York gallery Sargent’s Daughters, draws on the traditional Crow Fair Parade, held in Montana since 1904, creating a continuity between the Native American tribe’s past and future. Likewise, Carla Jay Harris’s series Celestial Bodies (2018-ongoing) at the Los Angeles gallery Luis De Jesus depicts ancient gods inhabiting the spaces where heaven meets earth, in the guise of peaceful and empowered Black characters.

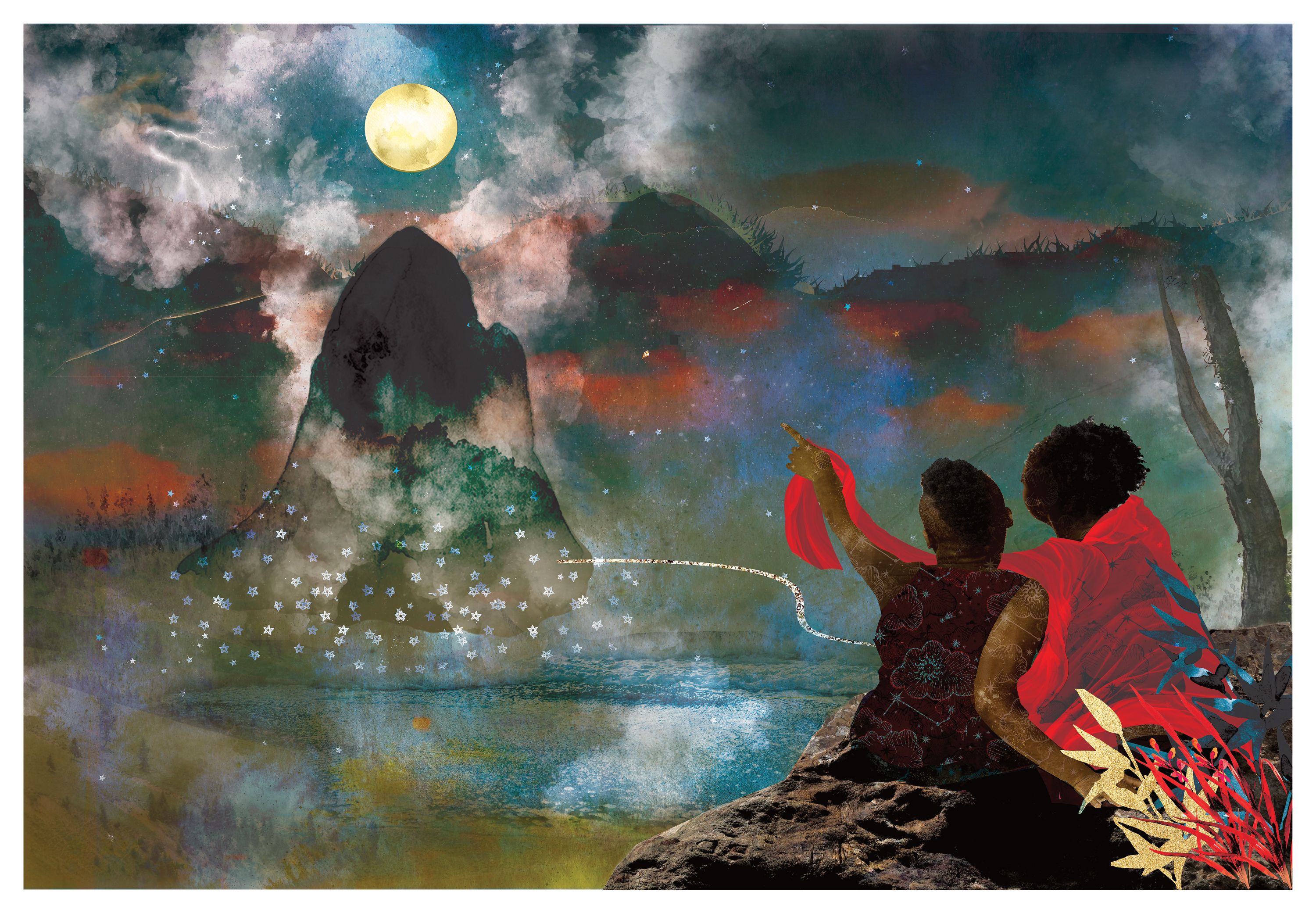

The present moment, it seems, is all about the future, and the Armory Show is not the only organisation tapping into it. Over at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, preparations are underway for the unveiling of Before Yesterday We Could Fly, an Afrofuturist “period room” slated to open on 5 November. Unlike other such displays at the museum, which recreate the domestic aesthetics of a specific point in time or a decorative movement, this iteration seeks to embrace the interconnected nature of the past, present and future of the African diaspora and Black communities. But such a different take on the period room also required a new curatorial and organisational approach.

“The collaborative curatorial process has been integral to the realisation of this project,” say Ian Alteveer and Sarah Lawrence, curators at the Met, who partnered with Hannah Beachler, the production designer on Marvel’s Black Panther, and Michelle Commander, an expert on the history of the Transatlantic slave trade, on the project. Alteveer and Lawrence say they also engaged “with a range of creative practitioners—ceramicists, graphic novelists, film-makers, artists and designers—who variously understand Afrofuturism in terms of their particular medium, their distinctive culture”.

In January 2020, they sought to further disrupt the usual hierarchy within the Met’s own community by holding a staff-wide conversation to share the project and its process with colleagues. “[We invited] not only our curatorial colleagues, but every single person employed at the museum,” the curators say. “This is something that had never been done at the Met, and the response was extraordinary.”

Meanwhile, kicking off in February 2022 at Carnegie Hall, an Afrofuturism festival will involve a string of cultural organisations presenting multidisciplinary programming rooted in “African and African-diasporic philosophies, speculative fiction, mythology, comics, quantum physics, cosmology, technology,” and more. There will also be online film screenings, exhibitions and talks with leaders within this eclectic and growing cultural sphere.

“Afrofuturism values humanity, the Earth and the universe at large,” says Ytasha Womack, speaking on behalf of the Afrofuturism festival’s curatorial team, which includes King Britt, Sheree Renée Thomas, Reynaldo Anderson and Louis Chude-Sokei, as well the designer Quentin VerCetty and the Carnegie’s director of festivals and special projects, Adriaan Fuchs. “I don’t see a great deal of hierarchy in how people approach the work, although hierarchies are often deconstructed within such works,” Womack says. “The narrative usually feels both of the times and in some way transcends it, stretching into futures and histories.”

The inclusive nature of Afrofuturism, and other kinds of non-European futurisms, creates a kind of open-source aesthetic with points of departure as well as attachment for creators of all stripes. “There’s something about seeing oneself as part of a larger continuum and a universe that is empowering,” Womack says.

Detroit ever was and always will be the city of tomorrow, and the Afrofuturist bedrock has given rise to new, expansive forms of POC futurism. Important figures now working in the city include the writer and activist Adrienne Maree Brown and her collectively produced science fiction book Octavia’s Brood; the artist and curator Ingrid LaFleur, who made a mayoral bid in 2017 and designs Afrofuturist experiences that have travelled worldwide; the writer Zig Zag Claybourne, whose experimental The Brothers Jetstream: Leviathan and its sequel, Afro Puffs Are the Antennae of the Universe, inject beguiling narrative devices and campy colour commentary into the sci-fi convention circuit; and the poet and revisionist historian Casey Rocheteau, whose Masters studies at the New School included a thesis on the two Black Panther parties in New York City.

At a recent workshop in Detroit on Habibi Futurism, the organisers Levon Kafafian and Kaymelya Omayma Youssef led participants through an immersive pageant of futurist thought, including the writing of Zaina Alsous, Angela Davis, Sun Ra, Audre Lorde, Octavia Butler and Kyle Carrero Lopez, the art of Serge Mouange and Etel Adnan, and the films of Bong Joon Ho. Following the presentation, participants responded to writing prompts delivered in the form of a card game that shuffled jumping-off points to generate SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) and non-SWANA future visions. “We want a more inclusive futurism,” says Kafafian, who also characterises POC futurisms as inherently rhizomatic in structure: connecting people and practices through a web of related roots.

Because there tends to be a premium placed on tangible objects or results in the art industry, people sometimes miss the fact that artists are, on a very fundamental level, problem-solvers. The problems of artists may be variously esoteric, logistic, material, historic or existential, but the process of art making is about grappling with these problems and finding resolution—or at least critique. It is not so far-fetched, then, to believe that artists can offer valuable perspective—and crucially, imagine what it is we need to do right now to get to any possible future.

“As we emerge from a year of so much challenge, much of which is ongoing, I wanted to invite conversations about how we might look forward into the near or distant future,” Al-Khudhairi says. “My intention was to consider the future on a spectrum—so it can be tomorrow or 100 years from today. I am interested in how artists can imagine ways to look at, think about, or desire futures. The urgency of ‘what’s next?’ was more about thinking of how to move forward in relation to all that has happened in the past year or so.”

The current interest in artists’ future visions also seems to be in destabilising the march of time, whether by critiquing the institutional norms of the period room, flattening the distinction between past and future, or seizing on the present day. The future may be yet to come, but Afrofuturism is now, and there is no time like the present for art to forge new pathways through reality.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/feature/futurism-a-product-of-our-difficult-times