Oral vaccines may be unlikely to work for people in low-income countries because a gut disorder common in these nations damages the immune response in the intestines, a new study finds.

Researchers in Pittsburgh studied a gut disorder tied to poor sanitation by simulating the condition in mice, studying its impact on the immune system.

Among the mice with this disorder, 18 times fewer vaccine-specific immune system cells developed in the small intestine compared to healthy mice.

The findings suggest that oral vaccines for COVID-19 and other diseases may be ineffective in the very countries that would find these vaccines most logistically useful.

But with better sanitation and antibiotics, vaccine effectiveness may be improved.

Oral vaccines are currently in development for Covid, but they may not work well in low-income countries, a new study suggests

As the Indian ‘Delta’ variant wreaks havoc across the world, public health experts have called for COVID vaccines to be made more readily available outside of wealthy nations.

To aid in this effort, some scientists are working on oral vaccines.

The Israeli company Oravax Medical is starting clinical trials for one such vaccine this summer.

And in the U.S., biotechnology company Vaxart has applied for Food and Drug Administration approval of its own oral vaccine.

Oral vaccines are particularly useful in low-income countries that lack the trained healthcare workers and other resources required for mass needle-based vaccination campaigns.

But a new study demonstrates why this type of vaccine may not work as well for people living in the very countries that most need the technology.

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh found that a gut disorder common in low-income countries impedes the immune system’s ability to respond to oral vaccines.

For the study, published on Tuesday in the journal Immunity, the team focused on a condition called environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) – caused by malnutrition and contaminated food and water.

EED often occurs in regions with poor sanitation. Infection from contaminated food and water systems – combined with a poor diet – triggers gut inflammation and damages villi, specialized parts of the intestine that absorb nutrients from food.

Globally, about 150 million children are at risk for EED thanks to their living conditions.

‘EED can affect anyone, but it’s a major problem in children because they’re still developing,’ said Dr Timothy Hand, senior author of the study and assistant professor of pediatrics and immunology at the University of Pittsburgh.

‘The result is that children with EED are stunted. They end up shorter in stature.

‘But perhaps more importantly, it can significantly affect brain development: These children have less cognitive ability. And this is a lifelong problem; you can’t restore that development later in life.’

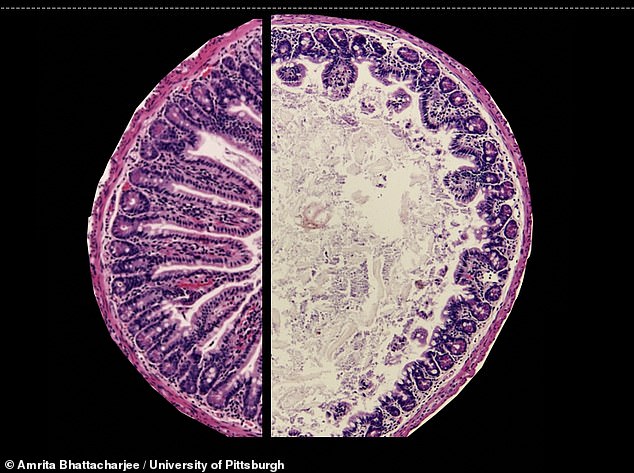

The left side of this image shows a healthy mouse intestine, while the right side shows a mouse with EED – the organ is inflamed and villi are damaged

Hand and the other researchers modeled EED in mice by giving the rodents a diet with limited nutrients, combined with Escherichia coli (E. coli) infection.

The gut disorder caused serious problems for the mice’s immune systems.

In the small intestines of mice with EED, about 18 times fewer vaccine-specific immune system cells developed compared to healthy mice

The EED mice also had stunted growth, inflammation in their guts, and changes to their guts’ microbiology compared to healthy mice.

Further investigation showed that immune system failure was tied to the mice’s gut microbiome – the bacteria, fungi, and other tiny organisms living in the digestive system.

EEd infection caused the mice’s guts to become inflamed, leading to a build-up of T regulatory (or Treg) cells.

‘Treg cells arise because there’s too much inflammation and they help tamp down that inflammation,’ Hand said. ‘But unfortunately, a side effect is that they prevent local accumulation of vaccine-specific CD4+ T cells.’

The researchers used antibiotics to treat the mice’s gut bacteria. After this treatment, vaccines were more effective – suggesting that similar treatments may work for humans.

As scientists continue to develop oral vaccines for COVID and other diseases, they need to account for differing sanitation and other public health factors in low-income nations.

‘If we could get flush toilets and plumbing to the world, we wouldn’t have this disease,’ Hand said.

‘What’s causing these chronic infections is that people are either drinking contaminated water or flies are transporting diseases from sewage to food.’

Hand and his team plan to continue investigating EED’s impact on vaccine effectiveness by working with researchers in countries with high rates of this disease.

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-9856475/Gut-disorder-common-low-income-countries-impair-immune-response-mouse-study-finds.html