Life-size camel sculptures in Saudi Arabia that were originally thought to be 2,000 years old actually date back 8,000 years, new analysis has revealed.

The discovery makes them almost twice the age of Britain’s Stonehenge, where stones were hauled into their unique circle around 2500 BC.

It had previously been estimated that the 21 camel, horse and other equid figures — found covered in stone in the Saudi desert in 2018 — were about 2,000 years old and had been made after the end of the Iron Age.

This is because they share similarities with artworks in the ancient Jordanian city of Petra, which was half-carved into rock around two millennia ago.

However, cutting-edge dating methods revealed that the estimate was out by 6,000 years, with the sculptures likely to date back to around 6000 BC when the now arid deserts of northern Saudi Arabia were ‘a savannah-like grassland scattered with lakes and trees’.

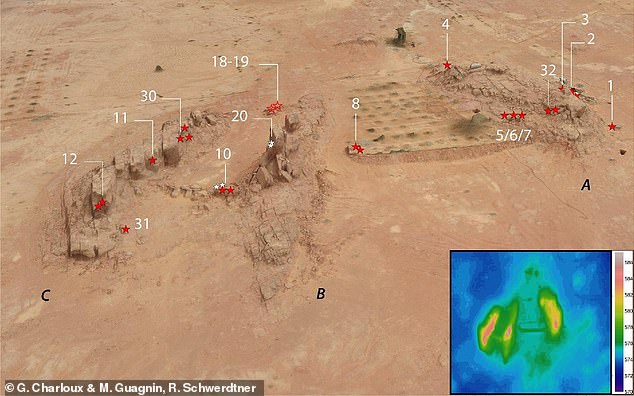

Life-size camel sculptures in Saudi Arabia (pictured) that were originally thought to be 2,000 years old actually date back 8,000 years, new analysis has revealed

It had previously been estimated that the 21 camel, horse and other equid figures — found covered in stone in the Saudi desert in 2018 — were about 2,000 years old and had been made after the end of the Iron Age

Rock art is extremely difficult to date, particularly at the ‘Camel Site’ (pictured) in the province of Al Jawf in north-west Saudi Arabia, where erosion has damaged the three-dimensional reliefs extensively

THE HISTORY OF ROCK ART IN SAUDI ARABIA

Human presence in the Arabian Peninsula dates back one million years.

Out of 4,000 registered archaeological sites in Saudi Arabia, 1,500 include rock art. The earliest examples date to around 12,000 years ago.

These depictions show masked men and women dancing, and experts believe they could be mythological figures, although the meaning remains unclear.

Between ten and eight thousand years ago people started herding animals and carrying out primitive agriculture.

During this period, drawings increasingly show cattle and dogs.

Experts believe these animals had been domesticated and were part of their everyday life.

Some include images of rare antelope, aurochs, wild camels and African asses, previously not known to live in this area.

Source: Bradshaw foundation

Advertisement

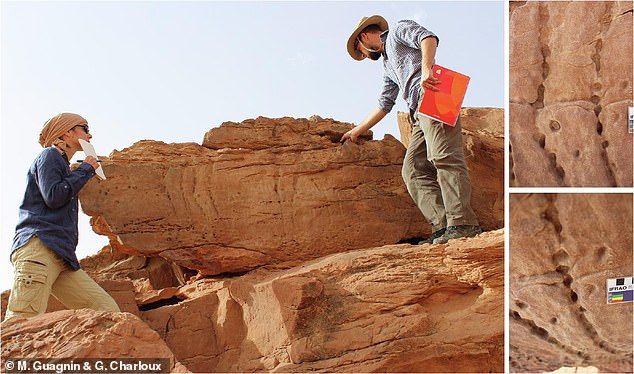

Rock art is extremely difficult to date, particularly at the ‘Camel Site’ in the province of Al Jawf in north-west Saudi Arabia, where erosion has damaged the three-dimensional reliefs extensively.

To establish an age for the site scientists assessed the tool marks and weathering on the sculptures, as well as fallen fragments and the density of the rock’s topmost layers.

The data indicated that the sculptures were made with stone tools during the 6th millennia, a time when tribes herded cattle, sheep and goats.

Wild camels and equids also roamed the area and were hunted for millennia.

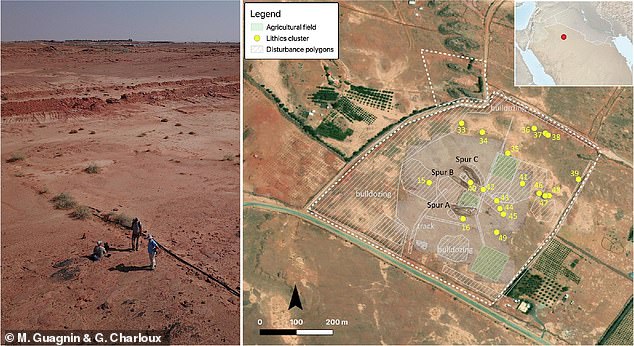

‘We can now link the Camel Site to a period in prehistory when the pastoral populations of northern Arabia created rock art and built large stone structures called mustatil,’ the study’s authors said.

‘The Camel Site is therefore part of a wider pattern of activity where groups frequently came together to establish and mark symbolic places.’

The research was a joint effort involving the Saudi Ministry of Culture, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, French National Centre for Scientific Research, and King Saud University.

Similar carvings of three-dimensional reliefs on the face of stone formations can be found in parts of Turkey but are rare in Saudi Arabia.

Researchers believe they were likely a communal effort, perhaps part of an annual gathering of a Neolithic group.

Reconstructions of the carving and weathering processes at the site suggest that it was in use for an extended period, during which panels were re-engraved and re-shaped.

Cutting-edge dating methods revealed that the estimate was out by 6,000 years, with the sculptures likely to date back to around 6000 BC when the now arid deserts of northern Saudi Arabia were ‘a savannah-like grassland scattered with lakes and trees’

To establish an age for the site (pictured) scientists assessed the tool marks and weathering on the sculptures, as well as fallen fragments and the density of the rock’s topmost layers

The data indicated that the sculptures were made with stone tools during the 6th millennia, a time when tribes herded cattle, sheep and goats

The research on the Camel Site (pictured) has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports

By the late 6th millennium BC most, if not all of the reliefs had been carved, making the Camel Site reliefs the oldest surviving large-scale reliefs known in the world.

‘Neolithic communities repeatedly returned to the Camel Site, meaning its symbolism and function was maintained over many generations,’ said the study’s author, Dr Maria Guagnin, from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

‘Preservation of this site is now key, as is future research in the region to identify if other such sites may have existed.’

Researchers believe the carvings were likely a communal effort, perhaps part of an annual gathering of a Neolithic group

Reconstructions of the carving and weathering processes at the site suggest that it was in use for an extended period, during which panels were re-engraved and re-shaped

By the late 6th millennium BC most if not all of the reliefs had been carved, making the Camel Site reliefs the oldest surviving large-scale reliefs known in the world

The Stonehenge that can be seen today is the final stage that was completed about 3,500 years ago.

According to the monument’s website, it was built in four stages, beginning around 3100 BC and and ending just after 1500 BC.

Some of the stones are believed to have originated from a quarry in Wales, some 140 miles (225km) away from the Wiltshire monument.

To do this would have required a high degree of ingenuity, and experts believe the ancient engineers used a pulley system over a shifting conveyor-belt of logs.

Modern scientists now widely believe that Stonehenge was created by several different tribes over time.

After the Neolithic Britons — likely natives of the British Isles — started the construction, it was continued centuries later by their descendants.

Over time, the descendants developed a more communal way of life and better tools which helped in the erection of the stones.

Bones, tools and other artefacts found on the site seem to support this hypothesis.

The research on the Camel Site has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports.

The Stonehenge monument standing today was the final stage of a four part building project that ended 3,500 years ago

Stonehenge is one of the most prominent prehistoric monuments in Britain. The Stonehenge that can be seen today is the final stage that was completed about 3,500 years ago.

According to the monument’s website, Stonehenge was built in four stages:

First stage: The first version of Stonehenge was a large earthwork or Henge, comprising a ditch, bank and the Aubrey holes, all probably built around 3100 BC.

The Aubrey holes are round pits in the chalk, about one metre (3.3 feet) wide and deep, with steep sides and flat bottoms.

Stonehenge (pictured) is one of the most prominent prehistoric monuments in Britain

They form a circle about 86.6 metres (284 feet) in diameter.

Excavations revealed cremated human bones in some of the chalk filling, but the holes themselves were likely not made to be used as graves, but as part of a religious ceremony.

After this first stage, Stonehenge was abandoned and left untouched for more than 1,000 years.

Second stage: The second and most dramatic stage of Stonehenge started around 2150 years BC, when about 82 bluestones from the Preseli mountains in south-west Wales were transported to the site. It’s thought that the stones, some of which weigh four tonnes each, were dragged on rollers and sledges to the waters at Milford Haven, where they were loaded onto rafts.

They were carried on water along the south coast of Wales and up the rivers Avon and Frome, before being dragged overland again near Warminster and Wiltshire.

The final stage of the journey was mainly by water, down the river Wylye to Salisbury, then the Salisbury Avon to west Amesbury.

The journey spanned nearly 240 miles, and once at the site, the stones were set up in the centre to form an incomplete double circle.

During the same period, the original entrance was widened and a pair of Heel Stones were erected. The nearer part of the Avenue, connecting Stonehenge with the River Avon, was built aligned with the midsummer sunrise.

Third stage: The third stage of Stonehenge, which took place about 2000 years BC, saw the arrival of the sarsen stones (a type of sandstone), which were larger than the bluestones.

They were likely brought from the Marlborough Downs (40 kilometres, or 25 miles, north of Stonehenge).

The largest of the sarsen stones transported to Stonehenge weighs 50 tonnes, and transportation by water would not have been possible, so it’s suspected that they were transported using sledges and ropes.

Calculations have shown that it would have taken 500 men using leather ropes to pull one stone, with an extra 100 men needed to lay the rollers in front of the sledge.

These stones were arranged in an outer circle with a continuous run of lintels – horizontal supports.

Inside the circle, five trilithons – structures consisting of two upright stones and a third across the top as a lintel – were placed in a horseshoe arrangement, which can still be seen today.

Final stage: The fourth and final stage took place just after 1500 years BC, when the smaller bluestones were rearranged in the horseshoe and circle that can be seen today.

The original number of stones in the bluestone circle was probably around 60, but these have since been removed or broken up. Some remain as stumps below ground level.

Source: Stonehenge.co.uk

Advertisement

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-9992791/Life-size-camel-carvings-Saudi-Arabia-TWICE-age-Stonehenge.html