View of “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” 2021, at the Jewish Museum, showing The Destruction of the Father, 1974. Photo Ron Amstutz/©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/Collection Glenstone Museum, Potomac, MD

View of “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” 2021, at the Jewish Museum, showing The Destruction of the Father, 1974. Photo Ron Amstutz/©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/Collection Glenstone Museum, Potomac, MD

Psychoanalysis is not dead. Merely repressed, it has returned, with a vengeance, to the Jewish Museum. “Louise Bourgeois: Freud’s Daughter” contains a smattering of the artist’s macabre sculptures, paintings, and drawings, but also—more freakily—eighty-two pages from her journals. It’s like an art exhibition turned inside-out, with books’ worth of text, text, text broken up by the occasional artwork. You’ll never be so relieved to see a head with pins poked into its eyes.

If Sigmund Freud had overdosed on cocaine as a young clinician, someone else could have discovered the principles of psychoanalysis by striking up a chat with Louise Bourgeois. It’s all there: the sexualized childhood, the fragile alliance with the mother, the hot-cold relationship with the father. Bourgeois began studying mathematics at the Sorbonne just two months after her mother died in 1932, for which tragedy she seems to have blamed her absent, philandering papa. Soon after, she married a man who was, by her own account, papa’s opposite; moved to Manhattan; and started on an oeuvre marked by ambiguous, writhing sculptural forms and unambiguous titles like The Destruction of the Father.

Some artists delight in refusing to explain themselves to critics. Bourgeois never stopped explaining herself. Her interview transcripts could paper the walls of two Jewish Museums, and when she died in 2010, she left behind roughly one thousand pages of notes authored concurrently with her three decades in analysis. The wall text doesn’t get into when or why, but Bourgeois apparently gave her blessing for these pages to be shared with the world—a fact that, as with this show’s pat, no-further-questions way of approaching them, I can’t help finding a tad suspicious. There’s something too perfect about Bourgeois’s ceaseless performance of Oedipal struggle, like a musical note that’s too clean and loud to come from a human throat.

More than once, the show reminds us of Bourgeois’s claim that “my art is my psychoanalysis.” Loosely taken, this means that her art served some therapeutic purpose as a means of confronting her difficult childhood. But Philip Larratt-Smith, the exhibition’s curator and Bourgeois’s literary archivist from 2002 until her death, is intent on taking Bourgeois more literally. He wants her art to be psychoanalytic to its core, her entire seventy-year career a pearl formed around the grain of “Oedipal deadlock,” as he puts it in an essay accompanying the exhibition. And if Bourgeois was a great artist whose art was fundamentally psychoanalytic, her psychoanalytic writings of course must be great too. “Bourgeois’s singular way of using language,” Larratt-Smith writes, “situates her in the select company of artist-writers like Cellini, Delacroix, Van Gogh, and Artaud.”

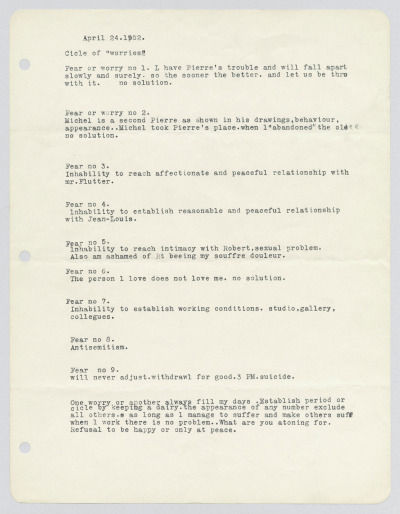

Louise Bourgeois, Loose sheet of writing, 1952, black ink on off-white paper. ©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Louise Bourgeois, Loose sheet of writing, 1952, black ink on off-white paper. ©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Singular” is a slippery word, but if Larratt-Smith means that his old boss’s writing has significant literary merit, I must disagree. Nothing in these dozens of pages matches the terse pathos of Vincent’s letters to Theo or the ecstatic cascades of Artaud’s manifestos. Not that there’s anything wrong with this—it wasn’t Bourgeois’s idea to build a show around her jottings. It’s not clear how much Larratt-Smith likes them either. Most of the passages he quotes seem to have been chosen for convenient mentions of Freudian buzzwords, not singular uses of language. For instance, “maybe towards my brother I / felt a wish to castrate.” Or “I literally cannot live or function / without the protection of a father.” Counterintuitively, many of the show’s most intimate pages are typed, not handwritten, like this from 1952: “One worry or another always fill my days. Establish period or cicle by keeping a dairy.” It’s not Virginia Woolf and it’s not trying to be, but notice how those sics sabotage the progress they seem to promise, as in the old joke where a guy says, “I gotta get organizized.” You could find Freud here if you tried, but the passage strikes me as more poignant: Bourgeois licks a wound no amount of analysis will heal or explain.

Larratt-Smith insists that Bourgeois’s “writings do not explain the sculpture.” Freud would have called this judgment a “reaction formation”; Shakespeare would have said Larratt-Smith doth protest too much. “During the Oedipal phase,” Larratt-Smith writes, after quoting a passage in which Bourgeois muses on her parents, “the child oscillates between maternal and paternal identifications. The merger of male and female in sculptures such as Fillette and Janus Fleuri (both 1968) reflects this alternation between male and female.” How is this not a way of explaining Bourgeois’s sculptures with her writings, connecting the dots to “discover” the Freud we already knew was there?

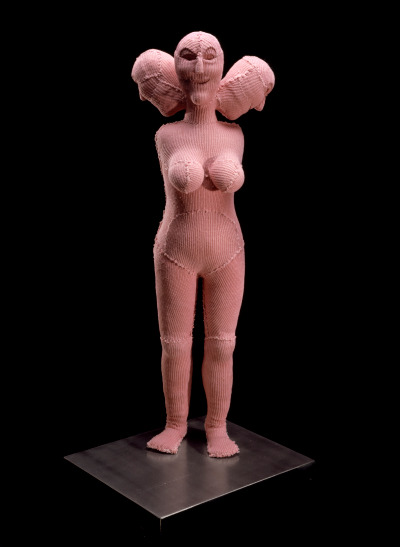

Louise Bourgeois, Hysterical, 2001, fabric, stainless steel, glass, wood, and lead, 18 by 8 by 6 ¼ inches. Photo Christopher Burke/©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/Collection The Easton Foundation

Louise Bourgeois, Hysterical, 2001, fabric, stainless steel, glass, wood, and lead, 18 by 8 by 6 ¼ inches. Photo Christopher Burke/©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/Collection The Easton Foundation

What’s missing, from this show and from many other post-mortem assessments of Bourgeois (see Jean Frémon’s 2019 novel Now, Now, Louison), is skepticism. In the face of so much self-conscious self-mythologizing, it’s important to distinguish Bourgeois the artist from what Robert Storr called “this character called ‘Louise’ that she performed and invented as she performed it.” In Larratt-Smith’s rendering, Bourgeois was a hermit who emerged weekly from her cave to talk to her analyst, when in reality she spent the first forty years of her career seeking fame and the last thirty savvily guarding it, throwing biographical and theoretical tidbits to eager critics like a farmer scattering chicken feed.

None of which means that Bourgeois didn’t have more than her fair share of grief and resentment, or didn’t take these things as a jumping-off point for artworks she considered Freudian. She did. But if her creations were as flatly Freudian as we’re told, only Freudians would care. Hysterical (2001), one of the few pieces on display that survives its textual smothering, may seem like a neat confirmation of the show’s thesis, from its three-headed fabric figure (id, ego, and superego?) down to its title. But the longer you look, the less Freudian it gets. What stick with you instead are the malevolent twinkle in the figure’s eyes, the sickly pink of the fabric, the stench of laudanum you imagine below the vitrine, the Duchampian prickliness that invites and repels interpretation. The more rules the exhibition insists upon, the more impishly disobedient the artworks become—and the more impressive Bourgeois seems. Like any artist worth a damn, she’s still a few steps ahead of her archivists.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/louise-bourgeois-jewish-museum-1234602433