Judy Chicago, Immolation, 1972. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco/Photo courtesy Through the Flower Archives

Judy Chicago, Immolation, 1972. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco/Photo courtesy Through the Flower Archives

While living in Fresno, California, during the early 1970s, Judy Chicago undertook a research project focused on female artists throughout the ages. These days, such an initiative hardly seems revolutionary—many books have since been published about pioneers by historians like Linda Nochlin, Griselda Pollock, Mary Garrard, and more. But at the time, art history as it existed in the U.S. was almost exclusively focused on the achievement of white males based in Europe and New York. Chicago sought to change that.

She learned that nuns aided in illuminating manuscripts alongside monks, and that women like Anna Claypoole and Sarah Peale were painting in the U.S. during the 19th century. She came upon the work of artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, the Baroque painter whose work has more recently acted as a symbol of the #MeToo movement, and Angelica Kaufmann, who during her day was among the most famous Neoclassical artists. She saw how paintings by Judith Leyster and Rosalba Carreira could offer visions of women by women, and how Impressionists like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot were forced to live in the shadow of their male colleagues. (Most of the women Chicago surveyed were white and European. Chicago has said her limited focus was due in part to the purview of the literature she relied upon.)

“Many of these artists struggled with obstacles similar to those I had encountered: negative attitudes toward women; not being taken seriously; and, most grievous, being deprived of the opportunities and rewards that allow one’s career to flourish,” Chicago writes in The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago, which was published earlier this year by Thames & Hudson. “Even in the face of innumerable impediments, including a lack of formal art training, they had carved out lives for themselves in a world where only male artists had the support of the culture.”

Since Chicago began her research project, many of the women she explored have been given proper museum surveys and biographies of their own. Now, Chicago has been inscribed in the lineage of which Gentileschi, Carreira, Morisot, and others are a part. This Saturday, the de Young Museum in San Francisco will open Chicago’s first-ever retrospective, cementing her place in history as one of the most important feminist artists ever. Though that show doesn’t include her most famous project, The Dinner Party (1974–79), it will feature a breadth of work that spans the full of her career, from early paintings done on car hoods to her latest series focused on death and ecological destruction. Below, a look at Chicago’s expansive oeuvre.

Judy Chicago, Birth Hood, 1965/2011. Photo Randy Dodson/©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Judy Chicago, Birth Hood, 1965/2011. Photo Randy Dodson/©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Early Feminist Experiments

People now know Judy Chicago’s name far and wide—but in fact, it wasn’t the moniker she was given when she was born to two Jewish liberals in Illinois’s largest city in 1939. Early on, the young Judy Cohen demonstrated a natural aptitude for art and was exposed to leftist politics, thanks to her father, who was a registered Communist. It wasn’t until the ’60s, after she had studied art at the University of California, Los Angeles and after her first husband had died, that she took on a new last name.

In 1966, she christened herself Judy Chicago on the advice of her dealer Rolf Nelson, who admired her Illinoisian accent. For a show at California State University, Fullerton, she exhibited a sculpture, along with a text offering insight into the name change: “Judy Gerowitz hereby divests herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance and freely chooses her own name: Judy Chicago.” The sculpture she showed was a set of semi-translucent acrylic half-spheres set atop a table-like structure. Smooth and sleek, it was of a piece with the Finish Fetish aesthetic that was pervasive in California at the time. It looked a lot like Minimalist sculpture—with key differences: it was a lot less imposing, and a lot more colorful.

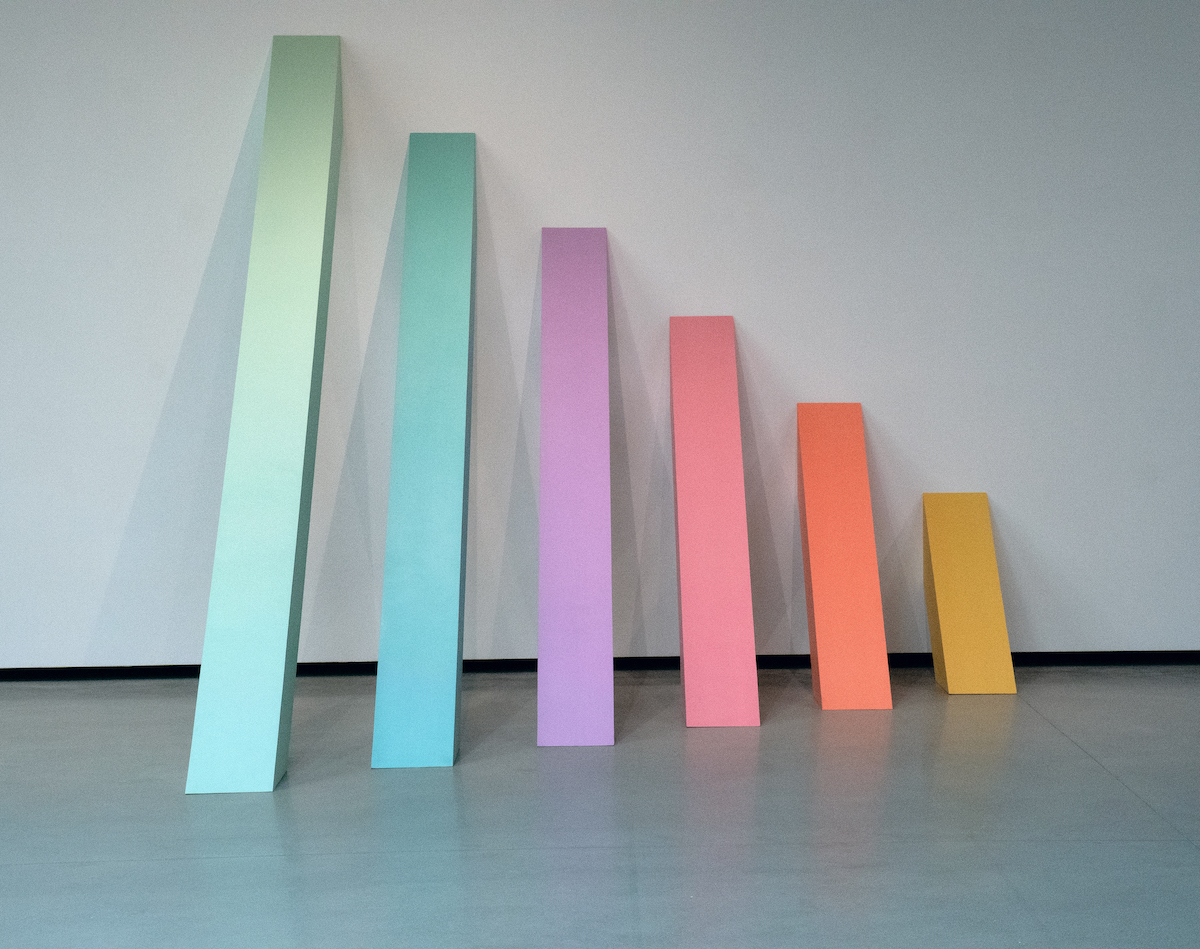

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Pickett, 1965. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman/Waldman Family Charitable Trust, Mountain Center, California

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Pickett, 1965. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman/Waldman Family Charitable Trust, Mountain Center, California

The Minimalist sculptors gaining name recognition at the time were largely white men based in New York making giant art out of industrial materials and mathematical systems. Chicago, who exhibited alongside them in Kynaston McShine’s famed 1966 show “Primary Structures” at the Jewish Museum in New York, took issue with this, and sought to find a way to create art that would be reflective of her own experience. One method was to generate a form of abstraction that referred directly to vaginas, vulvas, and breasts—a project she had begun in grad school with works painted on car hoods that collapsed male and female sex organs. (She would later return to making these abstractions throughout her career, producing them until 2004.) They were panned by her male colleagues and professors who saw them. Another was to make her repetitive forms colorful and quite unlike the steely creations being put out by the Minimalists.

But Chicago found herself frustrated with the abstract language she had engineered, since it couldn’t fully communicate her struggle as a woman. And so she ventured in a new direction.

Emily Dickinson’s place setting in Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party (1974–79). Photo Mary Altaffer/AP

Emily Dickinson’s place setting in Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party (1974–79). Photo Mary Altaffer/AP

The Life of the Party

During the ’70s, alongside many women across the U.S., Chicago joined the fight for women’s liberation. In response, her work began to tackle feminist themes more directly. Her practice also began expanding beyond gallery walls. For one series of performances, titled “Atmospheres,” she sprayed plumes of smoke amid arid landscapes, in an attempt to “feminize” her surroundings. (More recently, these works have been criticized for their ecological impact—a San Diego venue pulled out of hosting one in 2021 as part of the Desert X biennial, claiming that the smoke sculpture would hurt flora and fauna nearby.) Yet there were also projects from this era that looked nothing like art at all.

In 1970, Chicago started the Feminist Art Project at what is now the California State University, Fresno. Intended as a space for women, who were often marginalized at top art schools across the country, the Feminist Art Project was a part of Chicago’s consciousness-raising efforts, and was later redeveloped with artist Miriam Schapiro as the Feminist Art Program at CalArts. In 1973, Chicago would leave CalArts to cofound, with Arlene Raven and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, the influential Woman’s Building in L.A., where they hosted the Feminist Studio Workshop.

Chicago also made a space for women artists to make art, with Womanhouse, a 1972 project in which a Chicago, Schapiro, and other women artists, including their students, inhabited a Los Angeles house to create a collaborative Gesamtkunstwerk that included performances and installations there, drawing hundreds of visitors. Chicago’s contribution was Menstrual Bathroom, for which she lined a lavatory with feminine hygiene products that appeared to be used.

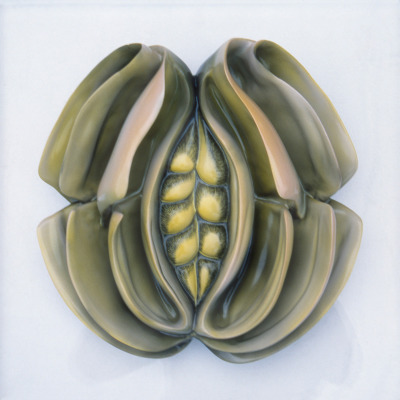

Judy Chicago, Virginia Woolf Test Plate, 1975–78. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman/Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Judy Chicago, Virginia Woolf Test Plate, 1975–78. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman/Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Many consider Chicago’s greatest work to be The Dinner Party (1974–79), an epic installation resembling a triangular table with place settings honoring women from throughout history, from Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut to American artist Georgia O’Keeffe. At each of the 39 settings was a plate depicting the sitter’s vagina, often with allusions to their artistic style or character. Beneath the table are tiles with the names of around 1,000 other women. The project was an example of the way Chicago began to merge “high” art with “low” craft techniques, such as a ceramics and embroidery, which had been historically been considered lesser than painting and sculpture because of their historical associations as so-called women’s work.

After premiering at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the installation toured the nation. Lucy Lippard called it “one of the most ambitious works of art made in the postwar period” in Art in America, although her critical admiration for the piece was rare at the time. The piece now resides at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, though this wasn’t meant to be the piece’s home—Chicago planned on giving it to the University of the District of Columbia, then rescinded the offer after Republicans in the House of Representatives called it “obscene” and withdrew funding for the school in 1990.

The Dinner Party marked one attempt to tell “‘herstory’ through techniques that were considered ‘womanly,’” as Chicago recalls in The Flowering, and it was met with big crowds and national media coverage. But not everyone sang its praises. Some accused Chicago of exploiting the workers she enlisted to produce the project—a charge she vehemently denies in her autobiography. Others claimed that Chicago’s dinner party had an exclusive invite list—few women of color made the cut. In 2018, Chicago explained this absence by telling the New York Review of Books that there was “little or no knowledge about any of these women” of color when she began working on The Dinner Party. When women of color do appear, they are often not placed on equal footing to their predominantly white company. Alice Walker famously focused on Sojourner Truth’s plate, which was one of the few that featured not a vagina but three faces. “It occurred to me that perhaps white women feminists, no less than white women generally, cannot imagine that black women have vaginas,” Walker wrote.

Judy Chicago, Birth Trinity: Needlepoint 1, 1983. Needlepoint by Susan Bloomenstein, Elizabeth Colten, Karen Fogel, Helene Hirmes, Bernice Levitt, Linda Rothenberg, and Miriam Vogelman. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman/The Gusford Collection

Judy Chicago, Birth Trinity: Needlepoint 1, 1983. Needlepoint by Susan Bloomenstein, Elizabeth Colten, Karen Fogel, Helene Hirmes, Bernice Levitt, Linda Rothenberg, and Miriam Vogelman. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman/The Gusford Collection

Born Anew

Since The Dinner Party, Chicago has worked predominantly in a figurative mode. After such a grand installation, Chicago’s next series was something more intimate: “The Birth Project,” which sought to right an art-historical wrong by offering depictions of mothers during labor that had rarely been seen throughout art history. Chicago attributed this absence to the patriarchy, saying, “If men had babies, there would be thousands of images of the crowning.” The resulting pieces, done via needlepoint and needlework, abstractly show children emerging from vaginas, with women’s bodies appearing to split open and emit rays of light in the process. At times, these images seem violent, even disturbing; at others, they are beautiful.

After this came “PowerPlay” (1982–87), a series of paintings in which a muscular male figure’s body appears to undergo various transformations—shedding his skin in one memorable work, and peeing all over a mountainous landscape in another. She continued her exploration of power and domination with “Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light” (1985–1993), which sought to understand the roots of a genocide that resulted in the killings of more than 6 million Jews and an estimated 5 million from other marginalized groups. Interwoven in it were meditations on colonial conquests in the U.S.

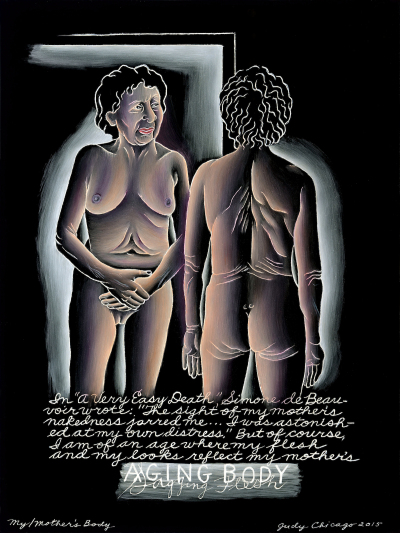

Judy Chicago, My/Mother’s Body, from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, 2015. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman

Judy Chicago, My/Mother’s Body, from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, 2015. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photo ©Donald Woodman

In recent years, Chicago has found widespread success. She now has representation with two galleries, Salon 94 and Jessica Silverman, and has said that her work’s appearance in a Getty Museum show about the postwar L.A. art scene, held as first of the Pacific Standard Time initiative, in 2011, helped cement her reputation. She has since designed the runway for a Dior show and appeared on the “TIME 100” list.

All the while, Chicago has continued making her politically engaged her art, directing much of her focus toward environmentalist concerns over the three decades. Building off concerns explored in bodies of work such as the needlework series “Resolutions: A Stitch in Time” (1994–2000), Chicago’s most recent series, “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015–19), is just as much a project about the horrors wrought by humanity on the natural world as it is on her own mortality. In these paintings done on black glass, sinewy humans are shown on their deathbeds, and animals are depicting crying out on pain. Amid the carnage, Chicago periodically sounds a hopeful note. In Stranded (2016), she shows a polar bear atop a shrinking icecap. Beneath it is a text quoting the environmentalist Derrick Jensen: “Every creature on the planet must be hoping that… our time of awakening comes soon.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/feature/who-is-judy-chicago-why-is-she-important-1234602444