Group 1 Carcinogens: What the Classification Really Means — And Whether Your Favorite Foods Are on the List

The phrase “Group 1 carcinogens” sounds dramatic. It immediately triggers alarm. Many people interpret it as: “This will definitely cause cancer.”

But here’s the reality — the classification system is often misunderstood.

Before panic sets in, let’s clarify what Group 1 actually means, how substances are classified, and whether your everyday foods are truly as dangerous as headlines suggest.

What Is a Group 1 Carcinogen?

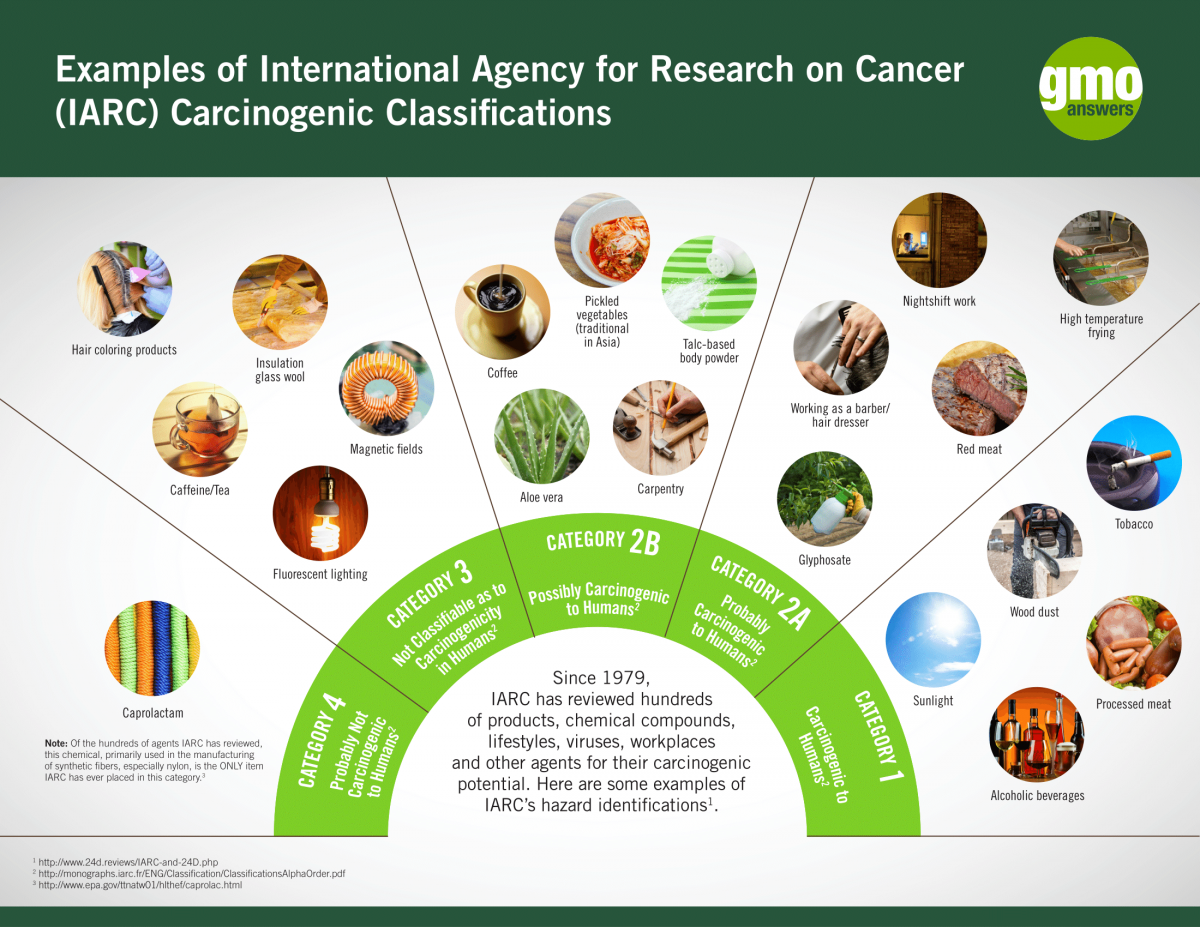

The term Group 1 carcinogen comes from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), part of the World Health Organization.

Group 1 does not mean “most dangerous.”

It means there is sufficient scientific evidence that the substance can cause cancer in humans under certain conditions.

This classification measures strength of evidence, not level of risk.

That distinction is critical.

For example:

-

Tobacco smoke is Group 1.

-

Asbestos is Group 1.

-

Processed meat is also Group 1.

But that does not mean eating bacon carries the same cancer risk as smoking daily.

Dose, frequency, exposure route, and individual susceptibility all matter.

Common Group 1 Carcinogens You Might Recognize

Here are some well-established Group 1 agents:

1. Tobacco Smoke

The leading preventable cause of cancer worldwide.

2. Alcohol (Ethanol in beverages)

Associated with cancers of the liver, breast, esophagus, and colon.

3. Processed Meats

This includes:

-

Bacon

-

Sausages

-

Hot dogs

-

Ham

-

Deli meats

Processed meats are classified as Group 1 due to evidence linking high consumption to colorectal cancer.

The mechanism involves:

-

Nitrites and nitrates forming carcinogenic compounds

-

Heme iron promoting oxidative damage

-

High-temperature cooking producing heterocyclic amines (HCAs)

However, risk increases with chronic high intake, not occasional consumption.

4. Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation

From sunlight and tanning beds — strongly linked to skin cancer.

5. Air Pollution

Long-term exposure increases lung cancer risk.

So… Should You Be Worried About Food?

The nuance is this:

Cancer risk is not binary. It’s probabilistic.

For example:

-

Smoking dramatically increases cancer risk.

-

Eating 50 grams of processed meat daily slightly increases colorectal cancer risk.

The absolute risk increase from moderate processed meat consumption is significantly lower than from tobacco use.

Context matters.

What About Burned or Charred Foods?

When meat is cooked at very high temperatures — especially grilling or pan-frying — compounds such as:

-

Heterocyclic amines (HCAs)

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

can form.

These compounds have carcinogenic potential in laboratory settings.

That doesn’t mean grilled food automatically causes cancer. It means:

-

Frequent heavy charring

-

Long-term exposure

-

High intake patterns

may increase risk.

Simple mitigation strategies:

-

Avoid heavy charring

-

Marinate meat before grilling

-

Cook at lower temperatures

-

Rotate protein sources

Understanding Relative vs Absolute Risk

This is where most misinformation spreads.

Let’s say a certain exposure increases cancer risk by 18%. That sounds alarming.

But if baseline lifetime risk is 5%, an 18% relative increase means risk rises to 5.9% — not 23%.

Relative risk without context is misleading.

Group 1 classification tells us the association is real, not that the magnitude is catastrophic.

Why Classification Matters

The IARC system is designed for:

-

Public health guidance

-

Regulatory policy

-

Research prioritization

It is not a fear-based ranking system.

Group 1 simply answers:

“Is there convincing evidence this can cause cancer in humans?”

It does not answer:

“How dangerous is it compared to everything else?”

Those are separate analyses.

Should You Eliminate Everything on the List?

Not realistically.

Sunlight is Group 1. Avoiding it entirely is impossible — and unhealthy.

Alcohol is Group 1. Moderate intake carries lower risk than heavy use.

Processed meat is Group 1. Occasional consumption within a balanced diet carries far less risk than daily high-volume intake.

The key variable across all carcinogens is dose and duration.

Smart Risk Reduction Strategies

Instead of reacting emotionally, apply structured prevention principles:

-

Do not smoke.

-

Limit alcohol intake.

-

Reduce processed meat consumption.

-

Avoid chronic heavy charring of foods.

-

Maintain healthy body weight.

-

Exercise regularly.

-

Increase intake of fiber-rich vegetables and fruits.

-

Protect skin from excessive UV exposure.

Cancer risk is multifactorial. No single food determines your outcome.

The Bottom Line

Seeing “Group 1 carcinogen” attached to a familiar food can feel shocking. But classification is about scientific certainty — not guaranteed harm.

Tobacco smoke, asbestos, alcohol, processed meat — all share strong evidence of carcinogenicity, yet their risk magnitude differs dramatically based on exposure patterns.

The real danger isn’t isolated ingredients.

It’s cumulative lifestyle patterns over decades.

Instead of fearing a label, focus on:

-

Frequency

-

Quantity

-

Overall diet quality

-

Long-term habits

Cancer prevention is not about perfection.

It’s about intelligent moderation and informed choices.

Understanding nuance protects you better than panic ever will.