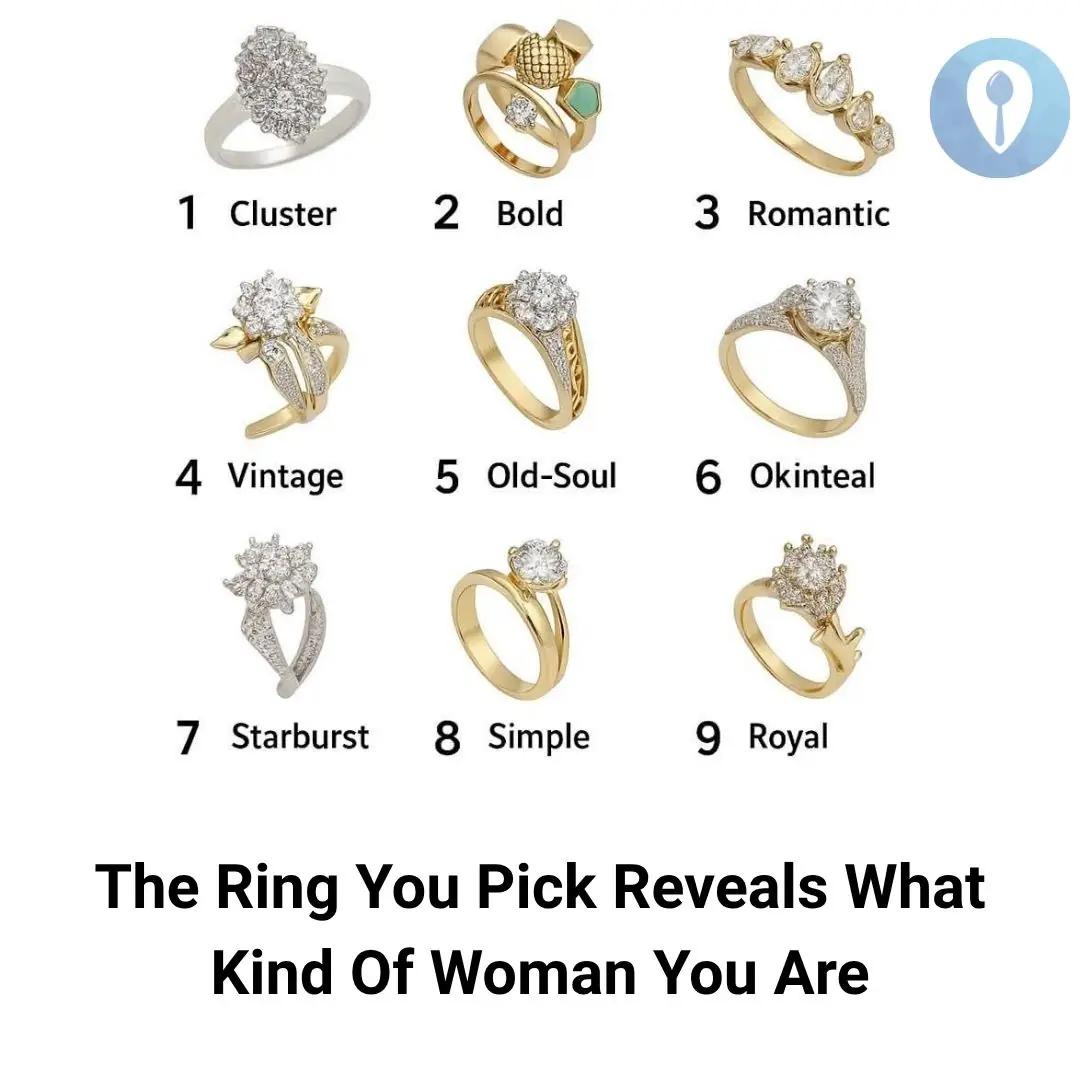

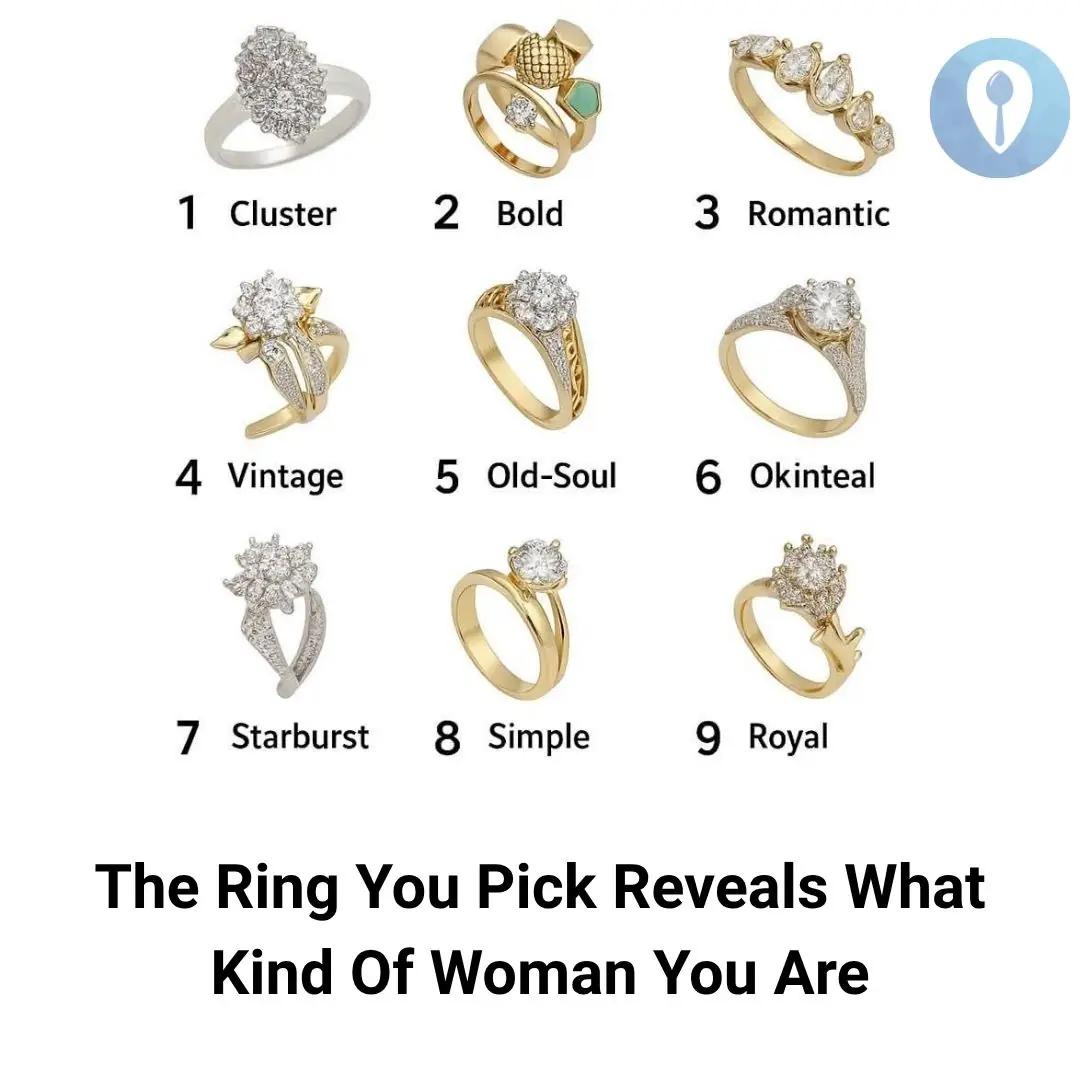

Pick a Ring and Discover What It Says About the Woman You Are

Relax 05/11/2025 12:02

The answer is: With a round hole in the middle of the chair, we can easily take the chair out from the pile of chairs stacked on top of each other by putting our hand into the round hole and pulling the chair out. This round hole helps the pressure to always be balanced, without the chair being "inhaled".