Yolanda López. Photo: Lex Mex

Yolanda López. Photo: Lex Mex

Yolanda M. López, the pioneering Chicana artist whose work reclaimed the iconography of the Virgen de Guadalupe in order to offer Chicanas and Latinas new ways of seeing themselves, has died at 79. The news was confirmed by her son, Rio Yañez, in a statement posted to Facebook, who said she passed away on the morning of September 3.

“The work that Yolanda did as an artist, activist, and mother continues with all of us. Keep on getting into good trouble,” Yañez wrote.

Jill Dawsey, a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, where a survey of López’s art will open next month, said in an email, “López was one of the most celebrated figures in the history of Chicano/a/x art, even as she was largely ignored by the institutional art world. She always prioritized her political commitments, working entirely outside the gallery system.”

During the mid-1970s, López started creating a now-iconic series of paintings and photographs in which the Virgen has been transformed into modern-day Chicana women. López’s intention was twofold: to show the world who Chicanas were and to create new and positive ways for Chicanas to see themselves. In her work, Chicanas are the empowered, beautiful, and complex women that they truly are. No longer are they idealized and made perfect, as is often the case with images of the Virgin.

Yolanda López, Victoria F. Franco: Our Lady of Guadalupe, from the “Guadalupe” series, 1978 Courtesy MCA San Diego

Yolanda López, Victoria F. Franco: Our Lady of Guadalupe, from the “Guadalupe” series, 1978 Courtesy MCA San Diego

In an artist’s statement from 1978, López wrote, “This omission and the continued use of such stereotypes as the Latin bombshell and the passive long suffering wife/mother negate the humanity of Raza women. The depth and breadth of our potential for moral, intellectual, spiritual and physical courage has rarely been displayed.” She would later add, in a 1999 interview with art historian Guisela Latorre, that the work was also “promoted by a need to critique, in her own words, even ‘progressive Chicanos.’”

For López, it was important to show that there was indeed beauty in all parts of the community—that our mothers and grandmothers were the ones that needed to be uplifted.

The best-known work from the “Guadalupe” series is her painting Guadalupe Triptych (1978). In Victoria F. Franco: Our Lady of Guadalupe, López’s grandmother is set atop a stool draped in the Virgin’s gold star blue cloak; she wears a pink maid’s outfit and holds what looks like a kid’s stuffed animal of a snake. Next comes Margaret F. Stewart: Our Lady of Guadalupe, in which López’s mother runs the cloak through a sewing machine; the snake stuffed animal becomes her pin cushion. On the right is Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe, which shows a beaming López wearing a pink dress and white sneakers. In her right hand she holds a snake, and in her left, she triumphantly clutches the cloak. Related to these works is López’s “Tableaux Vivant” series, which includes photographs shot by Susan Mogul featuring similar subject matter that acted as studies for the Guadalupe Triptych.

Yolanda López, from the series “Tableaux Vivant,” 1978. Photography: Susan Mogul. Courtesy Yolanda López

Yolanda López, from the series “Tableaux Vivant,” 1978. Photography: Susan Mogul. Courtesy Yolanda López

Of the “Guadalupe” works, Dawsey, the MCA San Diego curator, said, “One of most radical aspects of the image is its transformation of Guadalupe, a figure associated with her own suffering and grief, into one seen in a state of rebellious, unbridled joy.”

Today, the “Guadalupe” pieces are considered formative artworks within the field of Chicanx studies. But when they first debuted, they were not well-received. After their publication in Mexican magazines, López received bomb threats. Yet the artist came armed with her own defense against her detractors. Speaking to Elizabeth Martínez, López once told the journal CrossRoads that she was a “provocateur,” adding, “I looked at this religious icon of the Virgin, who was a symbol of Mexican nationalism, to see what it did for us as women. She was a role model; that’s what public images do, they feed us back a way that we should be, a way for us to compare ourselves to what we are.”

In another body of work begun in 1980, following the birth of her son, López considered how images in mainstream culture promote stereotypes that impact younger generations. In 1984, she debuted a wall piece called Things I Never Told My Son About Being Mexican, which collects various objects that kids are exposed to, such as a figurine called “Taco Terror,” an anthropomorphized taco holding a gun, who is described as having “taco breath” and being a “bean brain.”

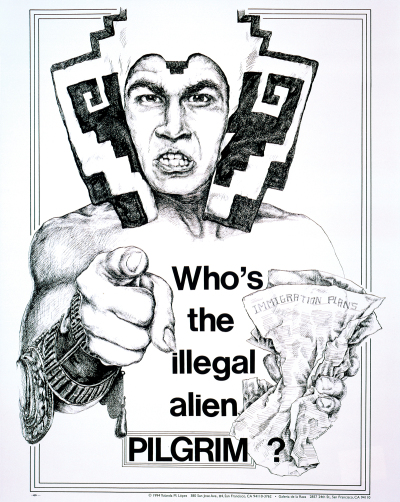

Yolanda López, Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?, 1978. Courtesy MCA San Diego

Yolanda López, Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?, 1978. Courtesy MCA San Diego

That work led López to create Cactus Hearts/Barbed Wire Dreams, which was first shown at San Francisco’s Galeria de la Raza in 1988. For that piece, López has created a life-sized version of a caricature of a Mexican man wearing a sombrero, who dozes next to a cactus. By reproducing this imagery at a large scale, López wanted to draw to attention to the insidiousness of what some might have seen as a harmless picture.

Often, López’s artistic and activist practices intersected. After graduating high school, she moved to San Francisco and began living in the Mission District, a historic Latinx neighborhood. She became involved in the Third World Liberation Hunger Strike in 1968 at San Francisco State University, which led to the creation of an ethnic studies program at the school.

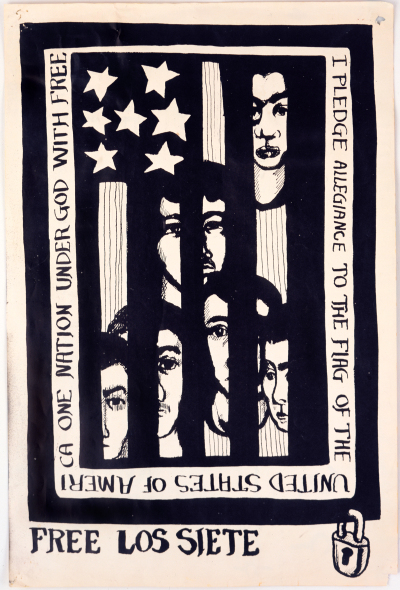

The following year, she became part of Los Siete de la Raza, a coalition which advocated for the release of seven young Latino men who had been arrested after being falsely accused of killing a police officer. Serving as the group’s artistic director, López created a poster, Free Los Siete (1969), in which the faces of these men are shown behind an inverted U.S. flag that appears like prison bars. That work was included in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s recent exhibition “¡Printing the Revolution!” The show’s curator, E. Carmen Ramos, wrote in the catalogue that López’s “poster circulated at rallies and in newspapers, and galvanized the Mission District’s Chicano and Latino community into a powerful social force with a noticeable presence in subsequent city politics.”

Yolanda López, Free Los Siete, 1969, as printed in ¡Basta Ya!, Courtesy MCA San Diego

Yolanda López, Free Los Siete, 1969, as printed in ¡Basta Ya!, Courtesy MCA San Diego

In 1978, López would create a poster in which an Indigenous man, holding a crumpled document reading “Immigration Plans,” points directly at the viewer, à la Uncle Sam, with the tagline: “Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?” The work alludes to a phrase commonly uttered by Western movie star John Wayne’s iconic address “pilgrim.” López’s piece was a direct response to Democratic president Jimmy Carter’s four-point immigration plan, which included a limitation on amnesty for undocumented immigrants already living in the U.S. Though widely circulated within California’s Latinx communities, the work also directly addressed white Americans, in particular those who traced their roots back to the Pilgrims.

A third-generation Chicana in the U.S., Yolanda M. López was born in 1942 in San Diego and raised in the city’s Barrio Logan neighborhood, a historically Chicanx community. A few days after graduating from high school in 1961, she left for the Bay Area to embed herself in San Francisco’s counterculture. In 1966, she began studying at San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University), where she quickly became entrenched in the school’s activist movements. She joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Third World Liberation Front, which led SFSC’s historic 1968 five-month hunger strike. The following year she would cofound the Los Siete de la Raza group, and she also served as the lead artist for the group’s important ¡Basta Ya! Newspaper.

In the early 1970s, López returned to San Diego and resumed her studies at San Diego State University, completing her B.F.A. in 1975. A few years later, she began an M.F.A. program at the University of California, San Diego, receiving her degree in 1979. Among her professors were Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler, who pushed her toward more conceptual ends in her practice. She soon moved back to San Francisco, where she was based for the rest of her life.

While in San Diego during the 1970s, López completed some of her most famous work. In 1975, she began her series of large-scale charcoal drawings “Three Generations: Tres Mujeres,” which consist of portraits the artist, her mother, and grandmother in different poses (as themselves and each other). Next came a series of painted self-portraits, titled “¿A Dónde Vas, Chicana? Getting through College,” in which López is shown running around UCSD’s campus. The figures in these works are intentionally larger than the buildings they are set against. In her 1978 artist statement, López described the series as “a confrontation between the woman and the institutional landscape.” Together, these two bodies of work would directly impact the imagery of the “Guadalupe” series.

In addition to her work as an artist, López served as the director of education at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts in San Francisco. She was also an important educator, training generations of art students at the University of California, Berkeley, Mills College in Oakland, and Stanford University.

Although it has always been considered foundational within the Chicanx community, mainstream institutions have only recently begun showing López’s art. In addition to her forthcoming MCA San Diego exhibition and her inclusion in SAAM’s “¡Printing the Revolution!,” López’s art was included in the acclaimed traveling exhibition “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” which was curated by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta and opened at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in 2017 as part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative. Earlier this year, she was one of the 15 recipients of the inaugural 2021 Latinx Artist Fellowship, funded by the Mellon and Ford Foundations and administered by the U.S. Latinx Art Forum.

Throughout her career, López’s dedication to creating art for the Chicanx community guided her groundbreaking practice. As said in the 1993 CrossRoads interview, “In many ways my stance as an artist, my intent, is the same as when I first decided that I wanted to be a Chicana artist. My audience is still other Chicanos and people like myself. Basically my work is geared to making Chicanos think; that’s all it’s intended to do. It’s not meant to convince them of any ideas, one way or another.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/yolanda-lopez-artist-dead-1234603270