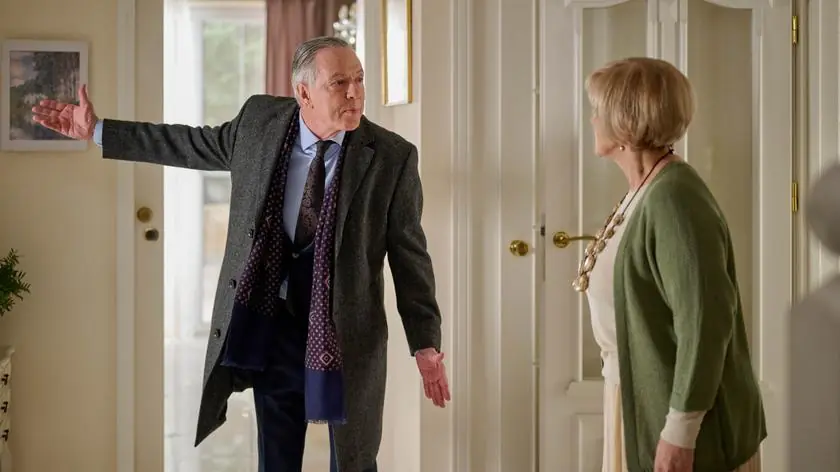

“You’ve been bleeding me dry for 38 years. From now on, every penny you spend comes from your own pocket!” he said. I just smiled. When his sister came for Sunday dinner and saw the table, she turned to him and said: “You have no idea what you had

“You’ve been bleeding me dry for thirty‑eight years. From now on, every penny you spend comes from your own pocket.”

Three months later, his sister looked at the Sunday dinner table like it was a crime scene and then looked at him like he was the criminal.

There was no roast beef resting in my grandmother’s chipped white platter. No mashed potatoes in the heavy glass bowl that had a faint crack running through one handle. No green beans tossed with slivered almonds, no warm rolls in the wicker basket with the blue checkered napkin.

Just a sweating tub of supermarket coleslaw, a plastic tray of deli meat still wearing its price sticker, a bag of store‑brand dinner rolls, and a store‑bought apple pie that had clearly taken a nose‑dive in the car.

Louise dropped her purse onto the chair and stared at the spread in stunned silence. Her husband Frank hovered behind her, eyes pinned to the mangled pie like a man watching a slow‑motion accident he couldn’t stop.

Walter stood at the end of the table, shoulders bunched under his golf polo, forcing a smile that was two seconds away from cracking. I sat in the armchair by the window with a paperback open on my lap, glasses slipping down my nose, pretending to be engrossed in a mystery novel I’d read three times already.

“Is this a joke?” Louise finally asked.

Her voice could cut glass when she wanted it to. It sliced straight through the quiet hum of the refrigerator, through Walter’s forced cheerfulness, through the paper‑thin peace that had settled over our house since March.

“It’s dinner,” Walter said, lifting a shaky hand toward the deli tray. “Turkey, ham, potato salad, rolls. There’s pie for dessert.”

Louise turned her head very slowly, like it hurt to move, and looked at me.

“Ruth,” she said, blinking. “Where’s the roast?”

I slipped a bookmark between the pages and closed my book, letting myself meet her eyes. “I didn’t cook today,” I said lightly. “Walter handled the menu.”

You could almost hear the gears grinding in her head.

Louise turned back to her brother, eyes narrowing. “You handled it,” she repeated.

Walter swallowed. I watched his throat move. A tiny, petty part of me savored the way his confidence wobbled.

“This is what we can afford now,” he said. “Things are different. We have… separate finances.”

He said the last words like they were sophisticated and modern, like he expected his sister to nod approvingly and call it progressive.

Instead, she stared at him for a beat, then looked down the table again. At the sweating coleslaw. At the thin, shiny slices of deli meat. At the crushed pie. At the single grocery receipt lying by the salt shaker, edges curled, numbers visible if anyone cared enough to squint.

She did.

Louise picked up the receipt with two fingers, scanned it, then looked back at me.

“What on earth is going on in this house?” she asked quietly.

I could have answered. I could have said, Well, Louise, three Sundays ago your brother announced I’d been draining him financially for thirty‑eight years and declared that my spending was no longer his concern. I could have told her about the masking tape dividing our refrigerator into two territories. About the spreadsheet. About the number forty‑seven thousand.

Instead, I leaned back, folded my hands over my book, and said, “Maybe Walter should explain.”

That was the moment everything finally cracked open. But the first fracture had appeared weeks earlier, on an ordinary Tuesday in March, with a bag of groceries in my hand and a sentence that would split our life in two.

That was the day my marriage’s invisible ledger finally hit zero.

—

The day it started, the sky over Maple Glen, Ohio, was the color of dishwater and the wind kept throwing little stinging bits of sleet at my face every time I stepped outside.

I remember that because the parking lot at Kroger was a mess of gray slush, and I nearly slipped twice pushing the cart back to my car.

I had spent the morning doing what I had done for most of my adult life: keeping a household running. Picking up prescriptions. Restocking coffee because Walter liked the dark roast from that specific brand. Buying bread and milk and eggs, chicken for a casserole, vegetables for a decent salad so I could feel like we still ate something that grew out of the ground.

I tossed a bunch of tulips into the cart at the last minute. They were on sale and the colors made me feel like spring might actually remember to come.

The total at checkout blinked up at me: $176.43.

I swiped the card we had shared for as long as I could remember and tucked the long curling receipt into my purse, along with all the other little paper witnesses to my quiet, ordinary crimes.

By the time I carried the bags through our back door, my fingers were numb. Walter’s SUV was in the driveway. His golf clubs leaned in their usual spot in the garage, still dusty from the last round. The house smelled faintly of coffee and the lemon cleaner I’d used on the counters that morning.

I kicked the door closed with my hip, stomping the slush from my shoes on the mat, and there he was.

Walter stood in the kitchen doorway with his arms folded across his chest. His chin was tipped up, the way it used to be when a student tried to argue with him in his office about a grade. Back then he’d been a partner at a financial consulting firm downtown, the man clients called when they wanted someone to tell them what they were doing wrong with their money.

Now he had retired that tone from conference rooms and brought it home.

“What did you buy?” he asked, without so much as a hello.

“Groceries,” I said, brushing past him to set the bags on the counter. My coat was damp, and I could feel melting sleet sliding down my neck. “Food. For the week.”

He didn’t move. His eyes tracked every bag I set down like each one contained contraband.

“Ruth, we talked about cutting back,” he said. “You’ve been spending like we’re still in our forties.”

I blinked at him. “I bought eggs and milk and a chicken, Walter, not a boat.”

He didn’t laugh. He didn’t even crack a smile. Instead he drew in a breath and delivered the sentence he’d clearly been rehearsing.

“From now on, every penny you spend comes out of your own pocket. I’m done funding your shopping sprees and your little luxuries. You’ve been bleeding me dry for thirty‑eight years, and it stops today.”

He said it in the same calm, measured tone he used to explain complicated tax strategies, like he was presenting a solution, not detonating a bomb.

I stood there for a long heartbeat, my hand still wrapped around a carton of eggs, my brain trying to match his words with the man I’d met in a college cafeteria when I was twenty‑one.

He had been funny then. Sweet. He used to bring me flowers on Fridays because he knew my student teaching days were long and the third graders could wear me down to a nub.

Back then, he’d spent his last ten dollars on discount roses from the grocery store to make me smile.

Now he was standing in our kitchen acting like the same grocery store had been my weapon of choice in a decades‑long robbery.

I set the eggs down very carefully. The carton made a soft little thud on the counter.

“If that’s what you want,” I said, my voice surprisingly steady, “all right.”

I could see the confusion flicker across his face. He’d expected a fight. Tears, maybe. Raised voices. A plate shattering in the sink. That’s how it went in his imagination, I think. He would proclaim his new policy, I would react emotionally, and he would feel justified.

Instead, I agreed.

His mouth opened, then closed. His arms slipped a fraction looser over his chest.

“Good,” he said finally, though it sounded less certain now. “We’ll separate everything. My pension, your pension. I’ll cover my expenses; you cover yours. We split the bills down the middle. It’s fair. Transparent. Gary says it’s the only way to keep things in check.”

Gary. Of course.

Gary was one of the guys from the firm, the sort of man who bought a new truck every three years and complained about taxes as if the IRS had personally ambushed him in the parking lot. Walter had gone on a three‑day fishing trip to Lake Tahoe with him and a couple of other retirees the week before.

Walter had come home smelling like campfire and cheap beer, with a sunburned nose and a gleam in his eye. Apparently in between rehashing old office gossip and comparing blood pressure medication, Gary had explained his revolutionary solution to “wives who don’t understand money.”

Separate accounts. Separate lives. Problem solved.

I wiped a melting drop of sleet off my wrist and looked at my husband.

“Your pension, my pension,” I repeated slowly. “Half the utilities, half the internet, half the property taxes. Everything else, we’re on our own.”

He nodded, relieved I was following. “Exactly. You have your own retirement income. You buy your things; I’ll buy mine. It’s not complicated.”

It wasn’t, actually.

It was brutally simple.

He was drawing a line through a life we had built together, splitting it into columns like a ledger. His. Mine. No more ours.

“Okay,” I said again.

And that was the moment, though he didn’t know it yet, when I stopped being the tired, apologetic woman sneaking scented candles into grocery bags and started being something much more dangerous.

I started keeping score.

—

I’ve been a teacher my whole life. Third graders, mostly. If there is one thing thirty‑two years in a classroom gives you, it’s an appreciation for structure and documentation.

You want to know who turned in their spelling homework and who mysteriously “lost” it on the bus? You keep a chart. You want to know which kid struggles with multiplication but will never ask for help out loud? You pay attention. You watch. You tally things other people don’t even notice.

So that night, after Walter had gone to bed—after he’d clicked off the TV and shuffled down the hallway in his slippers without kissing my cheek or saying goodnight—I sat at the kitchen table with my laptop and a legal pad and did what I did best.

I made a plan.

First, I logged in to our online banking. We had one main joint account we’d used for decades. Paychecks had flowed into it; bills had flowed out. It paid for soccer cleats and prom dresses, braces and broken water heaters, funerals and vacations and every grocery trip in between.

The balance stared up at me, a neat six figures that had taken years of brown‑bag lunches and canceled vacations and careful budgeting to build.

Walter wanted separate finances.

Fine.

I opened a new tab and created my own account at our credit union. I set up a transfer and, with the click of a trackpad, moved half of the joint balance into it.

Not a penny more. Not a penny less. Half.

My hands shook a little as I typed the amount, not from guilt but from the raw, unfamiliar sensation of drawing a boundary.

For thirty‑eight years, my default setting had been accommodate. Adjust. Explain. Smooth over. I’d watched him work late, watched him bring stress home from the office like a briefcase he never set down, watched him forget birthdays and dentist appointments and oil changes because his mind was always on “bigger things.”

I had filled in the gaps without ever putting my name on the ledger.

He had always called it “our money.” Until suddenly, it was “his.”

Now, I was simply taking my share.

When the transfer confirmation popped up on the screen, a strange calm settled over me.

Then I opened a spreadsheet.

In one tab, I created columns: date, item, cost, category. Groceries. Personal. Household. Medicine. Gas.

In another, I created a new sheet and wrote a title at the top in bold.

“Household & Walter – Last Ten Years.”

I am not fast with technology. But I am stubborn. And if you give a retired teacher an ocean of bank statements and a rainy week, she will find patterns you never wanted her to see.

That night I only had the energy to plug in the day’s numbers. $176.43, Kroger, mostly household. I saved the file and shut the lid.

The real work would begin in the basement with a stack of old shoe boxes.

That was the night my marriage stopped feeling inevitable and started feeling like a series of choices.

—

The next morning, I woke up at my usual time. 6:30 a.m. The house was quiet in that particular way it is right before a day starts, the air still holding the shape of dreams.

For thirty‑eight years, that quiet had been my cue to move.

Coffee, strong. Two mugs. Toast. Oatmeal or eggs, depending on his mood. Lunch packed if he was going to the office. Laundry started. Dishwasher unloaded. A hundred small, invisible tasks before Walter’s alarm even went off.

That Wednesday, I padded into the kitchen in my robe and fuzzy socks and made coffee.

One mug.

I measured out a single scoop of grounds into the machine, filled it with enough water for one generous cup, and hit brew. The smell filled the kitchen, warm and familiar, wrapping around me like a hug I’d forgotten to give myself.

I took my coffee to the small table by the window and sat in the chair that faced the backyard. The maple tree was just beginning to show tiny buds. Squirrels were already staging acrobatics on the fence line.

I ate yogurt with sliced banana and read the paper on my tablet.

At eight o’clock, Walter shuffled in.

He was wearing the same flannel pajama pants he’d received from Brian for Christmas three years ago and one of his faded university t‑shirts. His hair stuck up on one side.

He blinked at the empty counter, then at me.

“Where’s breakfast?” he asked, as if the concept of it appearing on its own were a law of physics.

“I already ate,” I said, scrolling to the next article.

“But… what about me?”

I kept my eyes on the screen. “You’re a grown man, Walter. There are eggs in the fridge. Bread in the pantry. You can make something.”

Silence.

Then I heard the refrigerator open, a cupboard door bang, the rattle of a pan being dragged out of the cabinet.

For twenty minutes, my kitchen sounded like a slapstick routine. Cupboards opening and closing. The sizzle of something hitting a pan too hot. The curse when a shell slipped into the eggs. The smell of scorched breakfast drifted across the room.

He ate alone at the counter. I didn’t look up.

It was a small thing, in the grand scheme. But in a marriage built on a thousand small things, taking one of them back can feel like an earthquake.

That was hinge number one.

—

At the grocery store that afternoon, I pushed my cart down the aisles with an unfamiliar lightness.

For the first time since my twenties, I wasn’t shopping for “us.”

I was shopping for me.

I picked up a small tub of Greek yogurt, a modest pack of chicken breasts, enough salad greens for the week, a few apples, an orange, a single ripe avocado because I liked it on toast.

I didn’t buy his favorite chips. I didn’t buy the brand‑name cereal he insisted tasted better than the generic. I didn’t buy extra coffee or the specific brand of jalapeño mustard only he touched.

At checkout, my total was $18.37.

I paid with my new card.

Back home, I took a roll of masking tape from the junk drawer and stretched a single line down the center of our refrigerator shelves. Left side. Right side.

On the left, I arranged my groceries. Yogurt. Vegetables. Fruit. On the right stayed the leftover pizza from two nights ago, the carton of milk that would go bad tomorrow, and half a jar of salsa.

I put a small sticky note on my side: “R.”

Walter came home from his afternoon golf game around four, cheeks pink from the cold, smelling faintly of cigar smoke and the cheap hot dogs they sold at the clubhouse.

He opened the fridge, then froze.

“What is this?” he demanded.

“Organization,” I said from the table, where I sat with my laptop open to my spreadsheet. “My food on the left, yours on the right. Fair and transparent. Just like you wanted.”

He stared at the nearly empty right side, then at the leafy abundance of mine.

“But I didn’t go shopping,” he said.

“That sounds like a personal problem,” I replied, and entered “18.37 – groceries – personal” into the “Ruth” column.

The first week was brutal.

For him.

For me, it was… illuminating.

In thirty‑eight years of marriage, Walter had never once done the weekly grocery run. Oh, he’d stopped to pick up a gallon of milk on his way home from work once or twice. But the careful planning, the list making, the pushing of a cart through crowded aisles under fluorescent lights? That had always been my realm.

He had no idea where anything was. The first time he went alone, he came home with two bags of chips, a frozen lasagna, a box of sugary cereal, and an enormous whole chicken he’d grabbed on sale because the price tag looked good.

He dropped the chicken onto the counter like he’d brought home a trophy.

“Great deal,” he said. “Five ninety‑nine.”

I looked at the bird, then at him. “Do you know how to cook it?”

Silence.

He frowned down at it as if it might offer instructions.

“There are recipes online,” I said, turning back to my book.

That night he watched three different YouTube videos, attempted to spatchcock the poor thing, gave up halfway through, and finally stuffed it in the oven at an arbitrary temperature.

We ended up ordering pizza when the smoke alarm went off.

By the end of that first week, he had spent over two hundred dollars on takeout and emergency grocery runs.

I had spent sixty‑three dollars. I ate grilled salmon, roasted vegetables, and salads that actually contained vegetables, not just iceberg lettuce and croutons.

I logged every receipt.

Numbers tell stories if you let them.

—

When I wasn’t watching Walter rediscover that food doesn’t magically appear in a refrigerator, I was in the basement, sitting on an overturned milk crate surrounded by old shoe boxes.

I’d always been a bit of a packrat with paperwork. Every time I emptied my purse, I’d tuck receipts into a box instead of throwing them out. Every December, when bank statements arrived in the mail, I’d slide them into a folder instead of tossing them.

Walter loved to tease me about it.

“Why do you keep all this junk?” he’d say, holding up a wad of gas station receipts.

“Just in case,” I’d reply.

I hadn’t known what “just in case” meant.

Now I did.

I opened boxes and spread papers out on an old card table. Electricity bills. Visa statements. Pharmacy printouts. The carbon‑copy pad from the plumber who came when the basement flooded five winters ago. The invoice from the appliance store for our replacement refrigerator. The receipt from the pro shop for Walter’s golf club membership renewal.

I hauled it upstairs in batches and, night after night, I typed.

Date. Amount. Category.

Groceries for the house. Gifts for his mother. Copays for his blood pressure medication. Airline tickets for trips we’d taken to Seattle and Denver to visit the kids. Registration checks for Brian’s soccer league twelve years ago. New tires for the car he drove long after I’d stopped going into work.

Every time the expense was clearly for both of us—or clearly for him—I put it in the “Household & Walter” column.

The numbers marched down the screen.

Forty‑seven dollars for his golf shoes on sale at Dick’s. Three hundred and nineteen for the emergency dentist visit when he cracked a tooth on a pistachio. Ninety‑nine for the bouquet I’d ordered online for his mother’s eightieth birthday party, when he forgot about it until the morning of.

The total at the bottom of the column crept up, digit by digit.

When I finally entered the last line item and hit “sum,” the number blinked up at me.

47,032.

Forty‑seven thousand and thirty‑two dollars.

That was what I had paid, personally, in the last ten years on things that benefited both of us—or specifically him.

The amount of my so‑called “bleeding him dry.”

My eyes stung.

Not because of the number itself, though it took my breath away, but because seeing it laid out in neat rows made something I had only felt in vague, bruised ways suddenly solid.

For ten years, I had quietly subsidized the life he took for granted.

And he had dreamed up a narrative in which I was the one draining him.

I closed the laptop.

I didn’t march into the living room and shove it in his face.

Not yet.

You don’t show all your cards at the beginning of the lesson.

Sometimes you let the student struggle a little first.

—

In our house, Sunday dinners had been their own religion.

Eight years earlier, when Walter’s father died and his sister Louise started coming over “to keep him from moping around the condo,” we’d fallen into a routine.

Sunday at five. Roast beef, mashed potatoes, green beans, fresh rolls, apple pie. If I ever deviated from that menu, Louise would wrinkle her nose and ask if everything was okay.

“Frank looks forward to your roast all week,” she’d say, patting her husband’s arm while he piled his plate.

The truth was, Walter looked forward to it too. He liked the performance of it: his wife bustling around the kitchen, his sister admiring the table, Frank loosening his belt a notch after dessert.

It made him feel, I think, like the center of something.

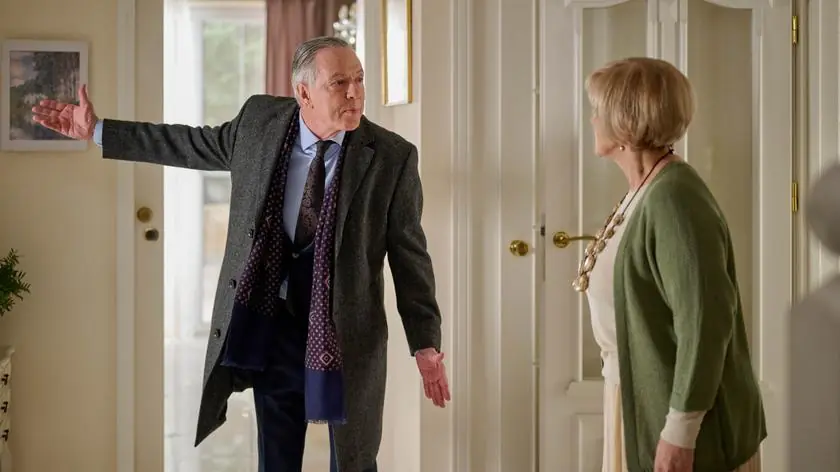

The Saturday three weeks into our financial Cold War, Walter wandered into the den while I was doing a crossword and said, “Don’t forget, Louise and Frank are coming tomorrow. You know she likes to eat by five.”

I filled in a six‑letter word for “regret” and didn’t look up.

“I’m not cooking,” I said.

There was a brief, disbelieving silence.

“Come again?”

“I’m not cooking,” I repeated, setting my pencil down. “Sunday dinner is your tradition, Walter. Your family, your guests. Under our new system, that makes it your responsibility.”

His face went through three color changes in as many seconds.

“Ruth, be serious,” he said. “Louise expects—”

“I used to spend my Saturdays shopping and my Sundays cooking for that expectation,” I said. “With my time. With my energy. With my money.”

I thought of the forty‑seven thousand sitting quietly in my spreadsheet. “That era is over.”

He opened his mouth, closed it, opened it again.

“How is this fair?” he asked.

I almost laughed.

“How is it not?” I countered. “You wanted us to each pay our own way. You told me you were done funding my luxuries. Feeding your sister and brother‑in‑law probably falls under your column now.”

He stared at me like I’d started speaking another language.

“That’s… ridiculous,” he said.

“Is it?”

He stood there for a moment, hands fisting at his sides, then turned on his heel and stomped down the hall. A minute later I heard the muffled sound of the TV flipping on.

I went back to my crossword.

Seventeen down: “A feeling of satisfaction after years of being underestimated.”

Not in the puzzle. But I could have filled it in myself.

Vindication.

—

On Sunday at three in the afternoon, Walter finally admitted defeat and went to the grocery store.

He had waited too long, of course. Procrastination had always been his weak spot. In college, he’d pulled all‑nighters writing papers he could have finished in daylight. At the firm, he’d leave PowerPoint decks until the evening before the presentation, growing increasingly irritable while I brought him coffee and closed the door so the kids wouldn’t disturb him.

Old habits don’t vanish just because you retire.

He stormed out of the house clutching a crumpled list he’d scribbled on the back of an envelope, muttering something about “how hard can it be to buy a roast?”

He was gone for three hours.

When he finally came back, his hair was flattened by the wind, and his cheeks were bright with frustration.

“I hate that place,” he announced, kicking the door shut.

“Kroger?” I asked mildly from my chair.

“The whole thing,” he said, dropping four overstuffed plastic bags on the table. “The carts are all wobbly, nothing is where it should be, and why are there fifteen different kinds of mustard?”

“Variety,” I said. “Consumers like choices.”

He glared, then began pulling items out of the bags.

No roast.

Instead, he’d bought a tray of pre‑sliced deli meats, an industrial‑sized tub of coleslaw, a bag of potato salad, store‑brand rolls, and a frozen apple pie. He’d forgotten to buy anything green.

He dumped the tub of coleslaw into my good serving bowl, as if that would magically make it homemade, and placed the pie on a baking sheet on the counter.

At 4:45, he looked at the clock, then at me.

“Are you seriously just going to sit there?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, turning a page. “I’m dying to see how this plays out.”

The doorbell rang at five on the dot.

Louise swept in, wrapped in a camel‑colored coat and indignation that hadn’t fully formed yet. Frank trailed behind her, shrugging out of his jacket, already sniffing the air for roast beef.

He didn’t find any.

“You smell that?” Louise asked, wrinkling her nose.

Frank inhaled again and frowned. “I smell… cabbage?”

“Coleslaw,” Walter said from the dining room, where he was laying out the deli tray like he was arranging evidence. “Come in, come in. Dinner’s almost ready.”

Louise hung up her coat and marched straight to the dining room.

She stopped short when she saw the table.

I watched from my chair, pretending I wasn’t.

“What is this?” she asked.

Walter forced a smile. “Turkey. Ham. Rolls. Coleslaw. Potato salad. And apple pie. It’s casual.”

“Casual,” she repeated slowly.

Her gaze swept the table, then the kitchen, where no pots simmered on the stove. No oven light glowed with anything other than a burning frozen dessert that should have gone in earlier.

Finally, her eyes found me.

“Ruth?” she called.

I set down my book and walked to the doorway.

“Yes?”

“Are you all right?” she asked, frowning. “Did something happen? Why on earth is Frank staring at packaged potato salad?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “I’m just off duty tonight. Walter wanted to handle dinner.”

If looks could kill, my husband would have been a chalk outline on our hardwood floor.

“Walter wanted to handle dinner,” she repeated.

“I can cook,” he said defensively. “We’re trying something new.”

Louise’s gaze sharpened. “What new thing?”

And so, because he still believed in his own righteousness, Walter told her.

He told her about Gary and the fishing trip and the genius idea of separating finances so wives couldn’t “bleed their husbands dry.” He told her about our new system: his pension, my pension, split bills, divided expenses. He even puffed up a little as he described how “fair” and “transparent” it all was.

Halfway through, Frank’s eyes had widened. Louise’s had narrowed.

When he finished, the only sound was the hum of the refrigerator.

Then Louise laughed.

It wasn’t a delighted laugh. It was a short, sharp sound that landed like a slap.

“Let me get this straight,” she said. “You, Walter James Harper, told Ruth—who has run this household since the Reagan administration, who raised your children, who planned every holiday and birthday, who cooked you a hot meal more nights than I can count—that she’s been bleeding you dry?”

“I didn’t say it exactly like that,” he muttered.

“How did you say it exactly?” she pressed.

He didn’t answer.

“That’s what I thought,” she said.

She turned to me, and her expression softened.

“Good for you,” she said quietly. “It’s about time you let him taste his own cooking.”

Frank cleared his throat. “We could still eat…” he began, eyeing the deli tray.

“No,” Louise said, picking up her purse. “We cannot. I am not sitting at this table and pretending this is normal.”

“Louise,” Walter protested, color climbing his neck.

She leaned in close to him across the table, her voice low and shaking.

“You have no idea what you’ve had all these years,” she said. “None. When you figure it out, when you apologize properly, maybe we’ll come back for roast beef. Until then, enjoy your coleslaw.”

She kissed my cheek on the way out.

“Call me later,” she whispered.

The front door closed with a solid, satisfying thud.

Walter stood there in the silence, surrounded by plastic containers and his own choices.

He looked smaller than I’d ever seen him.

That was hinge number two.

—

That night, after he’d pushed a few slices of ham around his plate and given up, I brought my laptop to the kitchen table.

“Sit,” I said, nodding at the chair across from me.

He lowered himself into it, eyes wary. “Ruth, I know Louise—”

“This isn’t about Louise,” I interrupted. “This is about numbers. Your favorite thing, remember?”

I opened the spreadsheet.

Rows and rows of expenses glowed on the screen, neat and undeniable.

“What is this?” he asked.

“This,” I said, “is ten years of receipts. Ten years of bills. Ten years of the things I’ve paid for that kept this house and your life running.”

I scrolled slowly, letting him read.

“The plumber,” I said. “When the upstairs toilet overflowed and was leaking into the kitchen ceiling? Three hundred and eighty‑five dollars. I paid that from my account.

“The new refrigerator when the old one died? Eleven hundred and change. I put that on my card.

“Groceries. Your prescriptions when you kept forgetting your wallet. Your mother’s birthday gifts. Our plane tickets to Seattle and Denver to see the kids. Your golf club membership.”

He flinched at that.

“I thought I paid the membership,” he said weakly.

“You did. The first year,” I said. “Then you asked me to ‘handle it’ because the billing annoyed you. And I did. Every year since.”

I scrolled to the bottom.

The total waited there, implacable.

“Forty‑seven thousand and thirty‑two dollars,” I said softly. “That’s the number, Walter. That’s what I’ve paid out of my pension, my savings, my little side tutoring jobs. On you. On us. In a decade.”

He stared at the screen.

The color drained from his face.

“I had no idea,” he whispered.

“I know you didn’t,” I said. “That’s the problem.”

He tore his eyes away from the numbers and looked at me.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” he asked. There was no accusation in it, just a genuine, bewildered question.

I closed the laptop.

“Because I shouldn’t have had to,” I said. “You live here too. You eat the food, sit under the roof, sleep in the bed, wear the shirts that come out of the dryer smelling like lavender. You should have seen. You should have noticed.”

He swallowed hard.

“I just thought…” he began, then stopped.

“You thought I was bleeding you dry,” I said quietly.

The words hung there between us, sour and heavy.

He dropped his gaze to his hands. His knuckles were white.

“What can I do?” he asked eventually, voice rough. “How do I fix this?”

I let the question sit.

I thought of all the times I’d asked myself some version of it, alone at two in the morning folding laundry while he snored down the hall.

I thought of the years I’d swallowed little hurts and told myself they were too small to mention.

“I don’t know if you can,” I said honestly.

His shoulders sagged, as if something inside him had finally given way.

That was hinge number three.

—

The next days were… strange.

Walter moved through the house like a man who had been handed glasses after years of squinting and suddenly realized everything was sharper, and not always in ways he liked.

He tried to help.

He folded laundry and turned all his white shirts pink by washing them with a red dish towel. He vacuumed the living room and somehow broke the belt on the vacuum cleaner. He attempted to cook spaghetti and forgot to salt the water, then overcooked the noodles until they resembled paste.

If it had been a sitcom, it might have been funny.

In real life, it was a slow, clumsy reeducation.

I didn’t swoop in to rescue him.

That was the hardest part.

For so long, my instinct had been to fix things before they broke, to anticipate needs and smooth rough edges.

Now I let things be messy.

One evening, about two weeks after the spreadsheet night, we were sitting in the living room when Brian called.

I put him on speaker.

“Hey, Mom. Hey, Dad,” he said. I could hear the faint hum of his Seattle apartment in the background, the muffled sound of a grandchild yelling about a missing toy.

We exchanged the usual pleasantries—weather, work, the kids.

Then, because he hadn’t learned yet that some things are better left unsaid until you’ve talked them through, Walter mentioned our “experiment.”

“Your mother and I are doing separate finances now,” he said. “Keeps everything clear.”

There was a pause.

“Why?” Brian asked slowly.

“Oh, you know,” Walter said, with a weak chuckle. “Your mom likes to spend. This way she handles her stuff; I handle mine.”

The silence on the other end of the line was not casual.

“Dad,” Brian said finally, his voice cooler than I’d ever heard it, “are you telling me that you told Mom she was spending too much of your money?”

“It’s not like that,” Walter said quickly.

“It sounds exactly like that,” Brian replied. “Do you have any idea what Mom has done for this family?”

The words came out in a rush, years of observations spilling over.

“Who was at every school play, Dad? Every parent‑teacher conference, every game, every piano recital? Mom. Who took care of Grandma when she was sick? Mom. Who made sure there was food in the house and clean clothes in the drawers and gas in the car? Mom. You worked hard, I know that. But you worked one job. Mom worked two.”

Walter’s face had gone very still.

“And you thought she was bleeding you dry?” Brian finished. “I love you, Dad. But that’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard you say.”

He didn’t wait for an answer.

“I’ve got to go,” he said shortly. “The kids are fighting over a Lego again. Mom, I love you. We’ll talk later.”

The line clicked.

Walter stared at the phone on the coffee table as if it might explain itself.

He looked… stripped.

Not of dignity, exactly, but of the comforting illusions he’d worn for years.

That night he didn’t turn on the TV.

He went to his office instead and closed the door.

I heard drawers opening and closing. Papers rustling. The printer whirring.

When he emerged an hour later, he was holding a stack of lined notebook paper.

He handed it to me without a word.

At the top of the first page, in his careful, accountant’s handwriting, he had written:

“Things Ruth Has Done for Me.”

The list ran for three pages.

Packed my lunch for work. Remembered my mother’s birthday every year. Organized our social calendar. Kept track of my medications. Scheduled doctor’s appointments. Paid bills on time. Planned vacations. Hosted holidays. Bought gifts and wrapped them. Sent thank you cards. Cleaned the house. Cooked dinner. Made coffee. Sat with me in the ER when I thought I was having a heart attack. Held my hand at my father’s funeral. Listened to me complain about work. Cheered me on when I got promoted. Edited my resume when I retired. Helped me pick out a suit for Brian’s wedding. Held our grandchildren the first time and cried with me.

At the bottom of the last page, he had written, in block letters:

“I AM AN IDIOT.”

My throat tightened.

He sat down on the edge of the coffee table, elbows on his knees, hands clasped.

“I’ve been thinking about this for days,” he said quietly. “About all the things you do that I never saw. It was like… magic. The house ran, the food appeared, the birthdays happened. I just assumed it was supposed to be that way. That it didn’t cost anything.”

His voice broke on the last word.

“It cost everything,” I said, not unkindly.

He nodded.

“I don’t want to live like roommates with separate spreadsheets,” he said. “I don’t want to be the kind of man my son looks at with disappointment. I don’t want Louise to be right when she says I have no idea what I had.”

He met my eyes.

“I want to go back to being partners,” he said. “Real partners. Where we both see what the other does. Where we both carry the load. I know words aren’t enough. Let me show you, Ruth. Please.”

There are moments in a long marriage when the ground shifts under you, when you realize the person across from you is not exactly who you thought they were—sometimes for worse, sometimes, against all odds, for better.

I looked at this man I’d met in a college library, the man whose hair was grayer now and whose hands trembled when he tried to thread a needle.

I thought of the good years. Of the way he used to dance with me in the kitchen to the oldies station. Of how he’d paced the waiting room floor all night when Patricia was born, wearing a groove in the linoleum.

I thought of the bad ones. Of slammed doors and cold shoulders and the way he’d made me feel small with a single raised eyebrow.

“I need time,” I said.

He nodded. “Take it,” he replied. “I’m not going anywhere.”

—

I talked to people.

I called Louise, who had already gotten the full confession from him.

“He’s called me four times since that dinner,” she reported. “The first time to defend himself. The last three to apologize. I think you scared him more than I ever have, Ruth.”

I laughed, a little shakily.

“You’re my hero,” she added. “Don’t rush. Make him sweat. But… if you decide to give him another chance, I won’t think you’re weak. I’ll think you’re braver than I am.”

I called Brian, who told me about the long email his father had sent, listing all the ways he’d fallen short as a dad and thanking me for “covering for him all these years.”

“He’s trying, Mom,” Brian said. “Really trying. I’ve never seen him like this.”

I had coffee with my friend Dorothy at the little café on Main where we used to meet after school on Fridays.

“Men don’t change at sixty‑six,” she said bluntly, stirring her latte. “But every once in a while, they notice something they can’t un‑see. Maybe that’s enough.”

I went home and sat at the kitchen table, staring at my spreadsheets and his list.

Forty‑seven thousand.

Thirty‑eight years.

Three pages of “Things Ruth Has Done.”

There was no equation that could make those numbers tidy.

In the end, what made the decision for me was something small.

I walked into the bedroom one afternoon and found Walter standing on his side of the bed, carefully tucking in the sheet.

He’d stripped the bed on his own. The comforter and pillowcases were piled in a basket by the door, waiting for the wash.

He looked up, cheeks pink.

“I watched a video,” he said. “Apparently you’re supposed to wash these more than twice a year.”

“You don’t say,” I replied.

He smiled weakly.

“I want to earn your trust back,” he said. “Not with big speeches. With this. With laundry. With dishes. With going to Kroger and not getting lost in the mustard aisle.”

Something in my chest unclenched.

“I can’t promise I’ll forget what you said,” I told him. “I can’t promise I’ll never be angry again when I think about those words. ‘Bleeding me dry’ is going to echo every time I look at a receipt for a while.”

“I know,” he said.

“But I can promise this,” I said. “If we do this—if we go back to shared finances, shared life—it’s not going to look like before. We track expenses together. We make decisions together. And you learn to see the work that doesn’t come with a paycheck.”

He nodded.

“Deal,” he said.

We shook on it.

It felt right that the new phase of our marriage started with something that simple.

—

We combined our accounts again.

This time, I sat beside him at the computer while we did it. We listed out our bills, our subscriptions, our insurance. We built a budget that reflected two people, not one provider and one invisible ghost.

We each started logging what we spent, not in a punitive way, but in a curious one.

“Did you know,” I said one evening, “that we spend almost as much on streaming services as we do on fresh produce?”

He blinked. “That can’t be right.”

“It’s all right here,” I said, turning the laptop so he could see.

He frowned, then laughed. “Cancel the one with the British baking show,” he said. “You just watch reruns of the same episodes anyway.”

“Never,” I said. “We’ll cancel the one with the fifteen superhero movies instead.”

He grinned.

We compromised.

We also divided up housework like we should have years earlier.

He took laundry duty twice a week. After the Great Pink Shirt Disaster, he learned to separate colors and whites. He bought himself a little laminated cheat sheet at the dollar store and taped it above the washer.

He cooked three nights a week. At first it was simple things—grilled cheese sandwiches, omelets, pasta with jarred sauce—but over time he branched out. I still remember the first time he successfully made that chicken stir fry recipe we’d clipped from a magazine in 1994 and never tried.

He burned the garlic, but the vegetables were crisp‑tender and the sauce tasted like something from a restaurant.

He did the dishes on the nights I cooked. He wiped down counters. He changed light bulbs before they burned out instead of waiting until we were eating dinner in moody semi‑darkness.

Every time he did one of those things, he would glance at me, as if to see if I was keeping score.

I was.

But the ledger in my head had shifted.

It wasn’t about who owed what anymore.

It was about whether the scales felt less tilted.

Most days, they did.

—

A month after the Sunday of the deli‑meat disaster, Louise and Frank came back for dinner.

I cooked.

Not because I had to, but because I wanted to.

Walter peeled potatoes at the sink while I seasoned the roast. He set the table without being asked, even remembering the cloth napkins Louise liked. He made the gravy, whisking in the pan drippings with a concentration usually reserved for tax returns.

When Louise sat down and took her first bite, her eyes widened.

“Oh, Ruth,” she said, sighing. “All is right with the world again.”

“The roast is all Ruth,” Walter said quickly. “I just assisted.”

Louise’s eyebrows climbed.

“Assisted?” she repeated.

He nodded.

“I peeled the potatoes. And I made the gravy,” he said. “And I went to the store yesterday with a list I wrote myself.”

Louise cut him a look, then glanced at me.

I smiled.

“Progress,” I said.

After dinner, Walter and Frank did the dishes while Louise and I sat in the living room with coffee.

“So,” she said, sipping. “Was the frozen pie worth it?”

“Every bite,” I said.

We laughed until our sides ached.

—

My friend Dorothy asked me recently if I ever regret not leaving.

I won’t lie and say the thought didn’t cross my mind.

There were nights, especially in those early weeks when he was stomping around the kitchen muttering about mustard, when I lay awake and imagined an apartment of my own.

A small place with bookshelves on every wall and plants on every windowsill. A place where no one questioned whether the brand‑name cereal was worth an extra dollar. Where the only coffee I made in the morning was mine.

I pictured myself there, peaceful and alone, the silence a choice, not a punishment.

I also thought about the man in the charcoal suit who’d paced hospital corridors with me when my father had his first stroke. The one who’d driven straight through the night from Ohio to Colorado when Patricia called crying from her residency, certain she’d made a terrible mistake.

People are not spreadsheets.

You can’t tally them up and decide, neatly, whether they are in the black or the red.

All you can do is ask: are they willing to learn? To see what they were blind to before?

Walter was.

That didn’t erase the hurt. But it changed the trajectory.

What I learned from all of this is that invisibility is the real enemy of a long marriage.

It’s not money, or chores, or whose name is on the mortgage.

It’s what happens when one person’s labor, one person’s heart, becomes wallpaper—always there, taken for granted, only noticed when a corner peels.

For thirty‑eight years, I let myself become invisible.

The groceries appeared. The bills got paid. The roast went into the oven every Sunday. The kids had clean uniforms and permission slips signed and birthday cakes baked. Walter’s life ran like a well‑oiled machine, and he never once lifted the hood to see who was turning the gears.

The day he accused me of bleeding him dry, something important snapped.

Not my love for him, not exactly.

My willingness to keep doing it unseen.

If you’re reading this and feel a little too familiar with my story, if you recognize yourself in the woman who always knows where the scissors are and who keeps the calendars and the passwords and the recipes, I want you to hear me.

You are not invisible.

Your work has value even if no one has ever put a dollar sign next to it.

You are allowed to stop doing things that hurt. You are allowed to draw lines. You are allowed to say, “If you think this is easy, try it.”

Sometimes, like in my case, the people around you will finally see the gap between what they thought you did and what you actually do.

Sometimes they won’t.

If they can’t or won’t see you—even when the grocery receipts pile up and the roast never hits the table again—then maybe they don’t deserve you at their table in the first place.

As I write this, Walter is in the kitchen.

It’s Thursday, his night to cook.

I can hear the clatter of pans and the hiss of something hitting hot oil. The smell of garlic and onion drifts down the hall.

He’s attempting chicken stir fry again.

It might be terrible. It might be wonderful.

Either way, he’s in there, apron on, sleeves rolled up, trying.

And after thirty‑eight years, that’s all I ever really wanted.

If this story found you somewhere between loads of laundry or in the parking lot of your own grocery store, I’m glad you’re here.

Tell me where you are in the comments if you feel like sharing—what city, what time of day you stumbled into my little corner of the internet.

I have a feeling there are more of us than anyone realizes.

And for once, I’d like us all to be counted.

I didn’t expect those last lines to echo anywhere beyond my own kitchen.

For most of my life, my stories stayed inside my head or, at most, between me and Dorothy over lukewarm coffee at the diner on Main. I was the listener, the nodder, the woman who held other people’s secrets in a mental file cabinet and locked the drawer.

Then Patricia came home for a long weekend.

She walked in from the airport with her carry‑on slung over one shoulder, stethoscope still in her bag, looking like every tired pediatrician you’ve ever seen and a little like the baby girl I used to rock at three in the morning.

“Mom,” she said, dropping her suitcase by the stairs, “Brian told me what Dad pulled with the money.”

I made tea. She paced.

“I can’t believe him,” she said. “Actually, that’s not true. I can. Men his age pull that control stunt all the time in my patients’ families. But I never thought he’d try it with you.”

“He tried,” I said. “It didn’t land the way he expected.”

She stopped pacing long enough to look at me closely.

“You’re different,” she said slowly. “You’re… lighter? What happened?”

I told her the whole thing.

The masking tape on the refrigerator. The deli‑meat dinner. Louise’s exit line. The forty‑seven thousand dollars. The list titled “Things Ruth Has Done for Me.”

By the time I finished, her tea had gone cold.

She sat back, crossed her arms, and let out a long breath.

“I spent my twenties telling myself I’d never get married because I didn’t want to disappear into someone’s life the way you did into Dad’s,” she said quietly. “I thought that was just how it had to be if you stayed. I didn’t… I never imagined you’d push back like this.”

“That makes two of us,” I said.

She smiled then, a crooked, watery smile.

“Have you ever realized someone was watching the way you lived and drawing conclusions about their own life that you never intended?” she asked.

The question hung there between us.

I thought of the years she’d spent insisting she didn’t “have time” to date, the way she rolled her eyes at romantic subplots in movies, the way she bristled whenever someone at church asked her when she was going to “settle down.”

“I guess I do now,” I said.

She reached across the table and squeezed my hand.

“I’m proud of you, Mom,” she said. “And I’m… rethinking a few things.”

That sentence was a hinge in its own right.

—

It was Patricia, naturally, who talked me into sharing my story beyond our kitchen table.

“You know how many women sit in my exam rooms and tell me about their migraines and their insomnia and their stomach pains,” she said, “and when I dig even a little, it turns out what they really have is a case of being everything for everyone? You should tell this story somewhere they can hear it.”

“I’m sixty‑three,” I protested. “I don’t even know how to record a video without my thumb blocking half the screen.”

“That’s why you have a daughter who can operate a smartphone,” she said. “We’ll keep it simple. You talk. I’ll handle the rest.”

So one Saturday afternoon, she set my phone up on a little tripod on the kitchen counter, angled toward the table where the light was good.

“Just pretend you’re talking to Dorothy,” she said. “Or to one of your third‑graders, thirty years older. Start where it matters.”

I looked into the tiny black circle of the camera and felt ridiculous.

Then I thought of the tape on the fridge.

I thought of Louise’s voice ringing out over a plastic tub of coleslaw: You have no idea what you’ve had.

And I started talking.

I told the story the way I’ve told it here, except this time my audience was an invisible someone on the other side of a screen. I didn’t shout. I didn’t cry. I just laid the facts out and let the quiet parts speak for themselves.

When I finished, Patricia wiped at her eyes.

“People need to hear this,” she said. “Can I post it?”

“Post it where?” I asked.

“On my account,” she said. “Or we can make you your own. GrandmaRuthStories. You can veto the name.”

I didn’t veto it.

Three days later, she called me from Denver between shifts.

“Mom,” she said, “you have no idea what’s happening.”

Apparently, thousands of strangers had watched me sit at my worn maple table and talk about masking tape and grocery receipts.

They had left hearts and little clapping emojis and, more importantly, long paragraphs.

I made an account just so I could read them.

Woman after woman wrote, “This is my life,” or “Are you secretly living in my house?” or “I thought I was the only one who kept boxes of receipts.”

One man commented, “I’m showing this to my wife and then I’m doing the dishes.”

I laughed until I cried at that one.

Have you ever read a stranger’s words on a screen and felt, for a moment, like someone had opened a window in a room you didn’t realize was suffocating you?

That’s what those comments did.

They cracked something open, not just for me, but, I hope, for the people typing them in break rooms and parked cars and quiet bedrooms after everyone else had gone to sleep.

—

With all that attention came an unexpected side effect: accountability.

“You know people are going to want updates,” Patricia said one evening on FaceTime. “You can’t just drop a forty‑seven‑thousand‑dollar bomb and vanish. That’s not fair.”

“Fair,” I repeated, amused. “Funny word choice.”

She grinned.

“Fair to them, Mom. Not to him.”

She had a point.

So I started jotting notes.

Not just about what Walter did—though that made the list—but about how I felt.

The first time he took the car in for an oil change without me reminding him. The night he set up the online bill pay himself and came into the living room holding his laptop like a science experiment.

“I think I did it,” he said. “The electric and the water are set to auto‑pay now.”

“Look at you,” I said. “Welcome to the twenty‑first century.”

The morning he woke up early on my birthday and made me pancakes that were slightly burned on the outside and gooey in the middle but arrived with flowers and coffee and a card where he’d written more than his name.

“That one goes in the plus column,” I told Dorothy later.

She stirred her coffee and eyed me over the rim of her mug.

“You two are becoming my favorite soap opera,” she said. “Except with less cheating and more spreadsheets.”

I snorted into my muffin.

“You think I’m kidding,” she added. “You should host a group. Invisible Wives Anonymous. I’d bring snacks.”

The idea lodged in the back of my mind.

—

Two months after deli‑meat Sunday, I walked into the Maple Glen Public Library and asked the young woman at the front desk how one went about reserving a meeting room.

She looked up my account, handed me a form, and smiled.

“What kind of group is it?” she asked.

I hesitated.

“Women over fifty talking about… unpaid labor,” I said finally. “We’re still workshopping the name.”

Her smile widened.

“Put me on the list,” she said. “I’m only thirty‑two, but I’ve been the default parent since my kid was born. I might learn something early.”

We met two Wednesdays later.

There were eight of us at the first meeting.

Dorothy, of course. The librarian, whose name turned out to be Mia. A nurse from the outpatient clinic. A woman who’d run the concession stand at the high school football field for fifteen years without ever getting a thank‑you from the principal. A retired postal worker. A pastor’s wife.

We sat in a circle of mismatched chairs under fluorescent lights that hummed faintly, sipping bad coffee from the vending machine.

“So,” Mia said, flipping open a notebook. “Invisible no more?”

The name stuck.

We went around and told our stories.

“They act like money that passes through their hands is more valuable,” the nurse said. “Like the dollars I earn working nights are somehow different from his because he has a 401(k).”

“My husband told me once that if I wanted spending money, I should get a ‘real job’ instead of volunteering at the church,” the pastor’s wife said, her voice shaking. “I run the food pantry that feeds half our county.”

We were angry.

We were tired.

We were also, to my surprise, hopeful.

Because every woman in that room had drawn some kind of line in the sand.

Some had left.

Some had stayed and renegotiated.

Some were still in the middle of the hard conversations.

“What would you do,” I asked them at one point, “if tomorrow you woke up and the person who does the invisible work in your house just… stopped? No groceries. No clean socks. No soccer sign‑ups. No appointment reminders. What would fall apart first?”

We all knew the answer.

Everything.

We met again the next month, and the next.

The circle grew.

I didn’t tell Walter all the details—those stories weren’t mine to share—but I told him enough.

“There are a lot of us,” I said one night as we loaded the dishwasher together. “Women who’ve been quietly holding up entire worlds for decades.”

He slid a plate into the rack and looked at me.

“I believe you,” he said. “I just wish it hadn’t taken me so long to see it.”

That was not nothing.

—

The real test of our new arrangement came in November.

Thanksgiving used to be my Mount Everest.

Turkey, three sides, two desserts, a house full of relatives, and a timetable that ran like a military operation.

This year, for the first time, we planned it differently.

Brian and his family were flying in from Seattle. Patricia was driving in from Denver with a coworker whose family lived too far away for a long weekend. Louise and Frank were, of course, coming, armed with opinions and an extra pumpkin pie.

“Let’s make a list,” Walter said, sitting at the table with a legal pad.

I nearly choked on my coffee.

“A list?” I repeated.

He smiled sheepishly.

“I used to make lists at the firm all the time,” he said. “Action items. Responsibilities. Timelines. It seems dumb that I never thought to apply that to what you do.”

“It’s not dumb,” I said. “It’s… new.”

We wrote it all down.

Who was responsible for the turkey. Who would mash the potatoes. Who would set the table and iron the napkins and clean the guest room and pick up Brian and his family from the airport.

Names went beside each task.

Not one column labeled “Ruth.”

When Patricia arrived, she studied the list on the fridge and whistled.

“Look at you two,” she said. “Running Thanksgiving like a joint venture instead of a dictatorship.”

On Wednesday night, the kitchen was a chaos of chopping and stirring and overlapping voices.

Walter brined the turkey according to a recipe he’d found online and printed out like a lab protocol.

Brian peeled potatoes while his kids made place cards out of construction paper. Patricia baked a pecan pie. Louise arrived with a salad and unsolicited commentary about everyone’s knife skills.

I made the stuffing.

Just the stuffing.

It was enough.

At one point, I stepped back, leaned against the doorway, and watched.

Walter caught my eye over the turkey pan.

“You okay?” he mouthed.

I nodded.

Better than okay.

Have you ever had a moment where the life you’d almost given up on suddenly tilted, and you realized you were standing in a different role than the one you’d been assigned for decades?

That was me, in my own kitchen, watching my family do work I used to carry alone.

On Thanksgiving Day, as we finally sat down at the long table in the dining room, Louise raised her glass.

“A toast,” she said. “To Ruth, for teaching my blockheaded brother some basic sense. And to Walter, for being smart enough to listen eventually.”

Everyone laughed.

Walter lifted his own glass.

“To Ruth,” he said, looking at me. “For seeing me even when I didn’t see her. And for letting me try again.”

My eyes stung.

Brian murmured, “Hear, hear.”

Patricia reached for my hand under the table and squeezed.

It wasn’t a perfect Hallmark moment.

The kids spilled cranberry sauce. The turkey was a little dry. The smoke alarm went off once when someone forgot the rolls under the broiler.

But it was ours.

And it was shared.

—

Not long after Thanksgiving, my body decided to remind me that sixty‑three is not twenty‑three.

I was in the laundry room, of all places, when it happened.

One minute I was pulling warm towels out of the dryer, breathing in the clean, cottony smell I’ve always loved.

The next, the room tilted.

Black dots crowded the edges of my vision.

I grabbed the edge of the washer to steady myself.

“Walter?” I called.

My voice sounded far away.

He was there in seconds.

He’d been in the garage, tinkering with a loose cabinet door.

“What’s wrong?” he asked, eyes scanning my face.

“Dizzy,” I said. “Just… give me a second.”

He didn’t.

He slid an arm around my waist, guided me carefully to a chair in the kitchen, and pressed his fingers gently to my wrist.

“Your pulse is all over the place,” he muttered.

“It’s probably nothing,” I said automatically.

He looked at me sharply.

“Forty‑seven thousand dollars is nothing,” he said. “This is not nothing.”

Before I could argue, he had his phone out.

He didn’t call Brian or Patricia.

He called 911.

The paramedics arrived within ten minutes.

By then, the worst of the dizziness had passed, but they still insisted on taking me to the ER “just to be safe.”

Walter rode in the front of the ambulance, then sat beside me in the curtained cubicle, his knee bouncing.

He answered all their questions.

He’d brought a list of my medications in his wallet—a list he’d insisted on carrying ever since my last physical.

“She’s the healthy one,” he told the nurse. “I’m the one who eats too much salt.”

They ran tests.

It turned out to be nothing dramatic—“benign positional vertigo,” the doctor said, handing me a sheet of exercises I could do at home and a prescription for anti‑nausea pills.

On the drive back, Walter’s hands were a white‑knuckled vise on the steering wheel.

“I kept thinking,” he said finally, voice hoarse, “about what this house would look like if you weren’t in it.”

I stared out the window at the winter‑bare trees and the Christmas lights our neighbors had already put up.

“What did it look like?” I asked.

“Like a spreadsheet with all the important cells blank,” he said.

He pulled into the driveway and shifted into park.

“I was a fool to ever treat you like an expense,” he said. “You’re the investment that made everything else possible.”

It was a corny line.

It was also the closest thing to poetry I’d ever heard him say.

Have you ever had a scare—a near‑miss, a sudden glimpse of how fragile everything is—that made you reevaluate who you’ve been taking for granted, including yourself?

That little spell in the laundry room did that for us.

For him, especially.

—

These days, life in Maple Glen looks ordinary from the outside.

There’s still trash to take out and gutters to clear and DMV appointments to endure.

We still argue sometimes—about the thermostat, about whose turn it is to call the insurance company, about whether we really need three streaming services.

The difference is, we argue as two people standing on the same side of the ledger.

On Thursdays, Walter cooks.

On Tuesdays, I film.

Yes, film.

GrandmaRuthStories somehow became a real thing.

I sit at my kitchen table with my phone propped up against a salt shaker, and I talk.

Sometimes I tell stories from my classroom days—the kid who hid a hamster in his backpack, the girl who finally read a whole book out loud without stumbling and burst into tears of pride.

Sometimes I talk about marriage: the good, the hard, the ways it can bend without breaking if both people are willing to do the bending.

Sometimes I talk about money—not in terms of budgeting apps and investment portfolios, but in terms of value.

About the cost of the mental load.

About what it means to be the one who remembers everyone’s birthdays and shoe sizes and food allergies.

People listen.

They comment.

“Which moment in this story hit you the hardest?” I asked not long ago under the video about Walter and the forty‑seven thousand dollars. “Was it the masking tape on the fridge? Louise walking out on deli‑meat Sunday? Brian calling his father out? The list titled ‘Things Ruth Has Done for Me’? Or the ambulance ride that made him imagine this house without me?”

The answers poured in.

Some people picked the tape.

Some picked Louise.

A surprising number picked the list.

A few said the moment that hit them hardest was none of those.

“It was when you finally said ‘all right’ and meant it,” one woman wrote. “Because I’m still stuck at the part where I swallow everything and say nothing.”

I sat with that one for a long time.

If you’re reading this and you recognize yourself in her, I hope you know this: your first boundary doesn’t have to be dramatic to be real.

It doesn’t have to be a shouted ultimatum or a packed suitcase.

Sometimes it’s as simple as a line of tape on a refrigerator shelf.

Sometimes it’s a quietly opened bank account.

Sometimes it’s a sentence said in a steady voice at a kitchen counter: From now on, I’m not invisible.

If you feel like sharing, especially if you’re reading this on Facebook where strangers’ stories bump up against your own, I’d genuinely love to know: what was the first boundary you ever set with your family? Was it saying no to hosting another holiday you couldn’t afford? Refusing to be the only one who remembered every appointment? Deciding to go back to school when everyone told you it was “too late”?

There’s no wrong answer.

Every line in the sand counts.

For years, I thought the only way to keep the peace was to hold everything together by myself.

Now I know the truth is more complicated and, in its own way, more beautiful.

Peace isn’t me carrying the whole load with a smile.

Peace is all of us picking up a piece of it.

If my little story from a kitchen in Ohio can nudge even one person closer to that kind of peace, then the forty‑seven thousand dollars, the deli meat, the masking tape, and even the dizzy spell in the laundry room will have bought something priceless.

And if you’ve read or listened this far, wherever you are, whatever time it is, know this much:

You are not alone.

You are not crazy.

You are not asking for too much.

You are simply, finally, asking to be seen.

That is the first penny you get to keep in your own pocket.