Many people will answer wrong for sure

Many people will answer wrong for sure

Answer: Number 4 when he took a saw and cut off the branch he was sitting on.

Number 4 became the correct answer when he made the unwise decision to take a saw and cut off the branch he was sitting on. This action perfectly exemplifies a self-defeating move, as by cutting the very branch that supported him, he caused himself to fall. It’s a metaphor often used to highlight the consequences of actions that undermine one's own position or stability. In this case, the humor and irony lie in the lack of foresight, as the person fails to realize that their action directly leads to their downfall. The scenario serves as a reminder to carefully consider the outcomes of our decisions, especially when they have the potential to affect us negatively.

News in the same category

Why shouldn't you set the air conditioner to 26°C at night?

9 out of 10 people store onions incorrectly: Here's why you shouldn't keep them in the fridge

Smart travel tip: Why you should toss a water bottle under your hotel bed?

Don't throw away your yellowed white shirts - try this soaking method to make them bright and as good as new

Easy lemon storage hacks that keep them fresh for a long time

Natural Pest Control: Using Diatomaceous Earth and Cloves Against Bed Bugs and More

Tips to Quickly Get Ants Out of Sugar Jars and Keep Them Away for Good

Common causes of water leaks from air conditioners and how to fix them.

Keep Ginger Fresh and Intact for a Long Time With This Simple Trick

Mix cloves, honey, and cinnamon and you will thank me! This is my grandmother's secret...

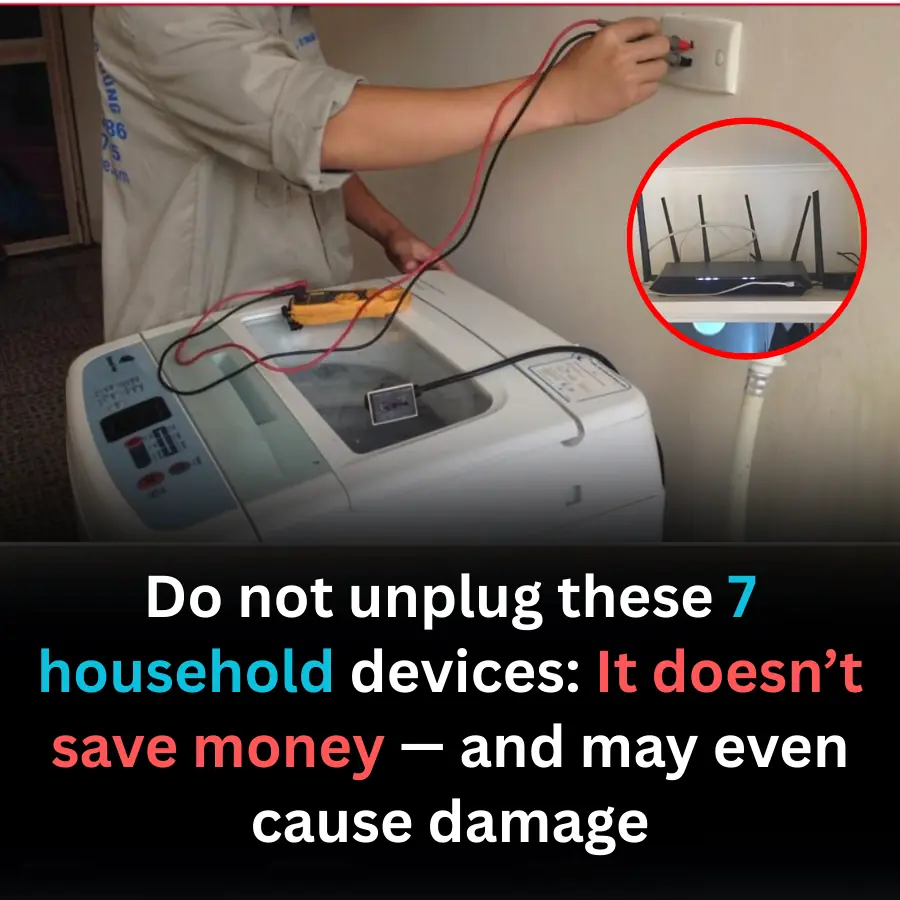

Experts Warn: Never Unplug These 7 Household Devices — You Won’t Save Money, and It Could Cause Even More Harm

A 3-Year-Old Boy Nearly Blinded by 502 Super Glue

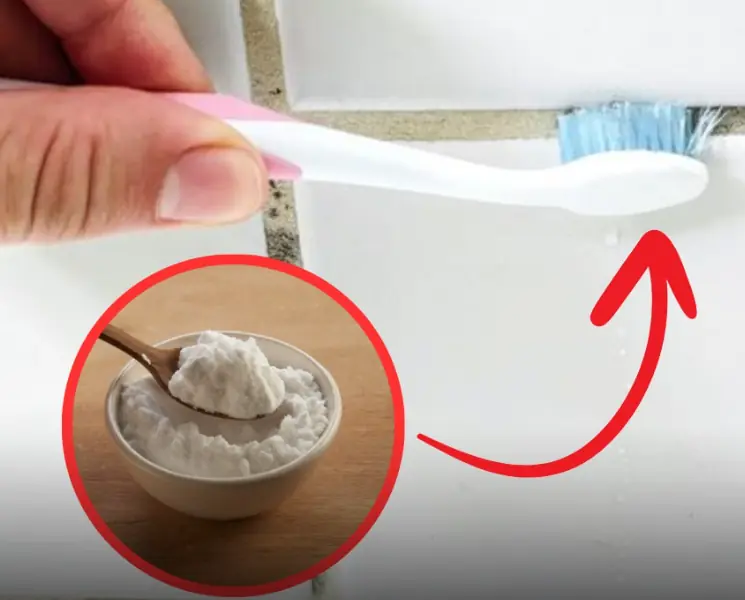

Simple hack to remove mold from bathroom grout using just 2 common ingredients - Better than bleach!

Smart people unplug the TV when checking into a hotel - Knowing why you will do it immediately

Don’t Throw Away Lemon Peels: Smart, Natural Ways to Clean and Freshen Your Home

Why smart travelers always unplug the hotel TV when they arrive?

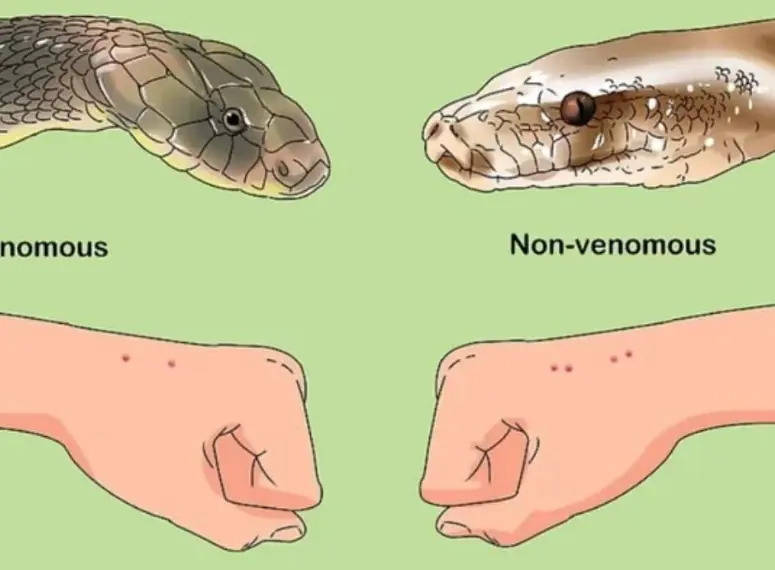

When bit.ten by a snake, you should do these things first

This Button on Your Car Key Is Something 90% of Owners Have Never Used — Yet It Could Save Your Life in an Emergency

Health Experts Warn: This Common Fruit Contains the Highest Pesticide Residue and Should Be Avoided If Not Properly Washed

News Post

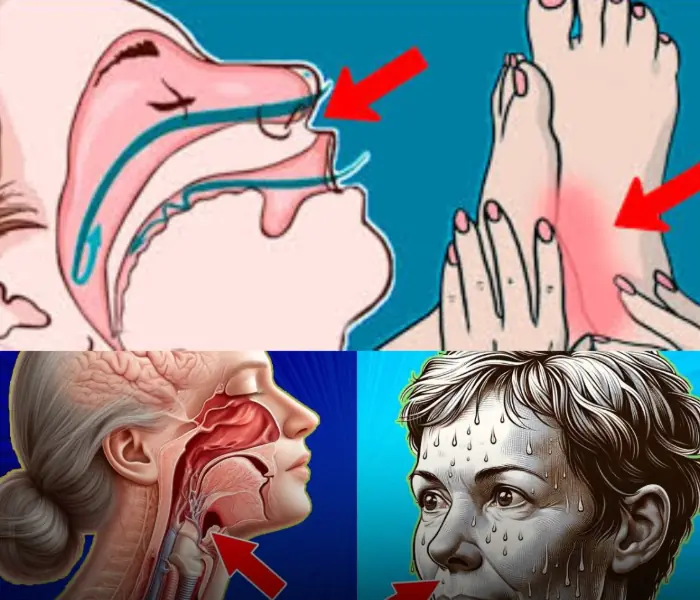

Doctors shocked after a 52-year-old man’s d.e.a.th — this habit was the cause

If Your Parent Shows These 3 Signs, They May Be Nearing the End of Life. Prepare Yourself for What’s to Come

Leftovers Can K.i.ll: 5 Foods to Never Keep Overnight

4 types of people who should avoid eating cucumbers

A ha.rmful habit that many of us may also have

The Military Sleep Technique That Can Help You Fall Asleep in 2 Minutes

Eating Eggs Every Day: The Surprising Effects on Your Body

A 20-year-old man contracted three pa.rasites at the same time - linked to eating this vegetable

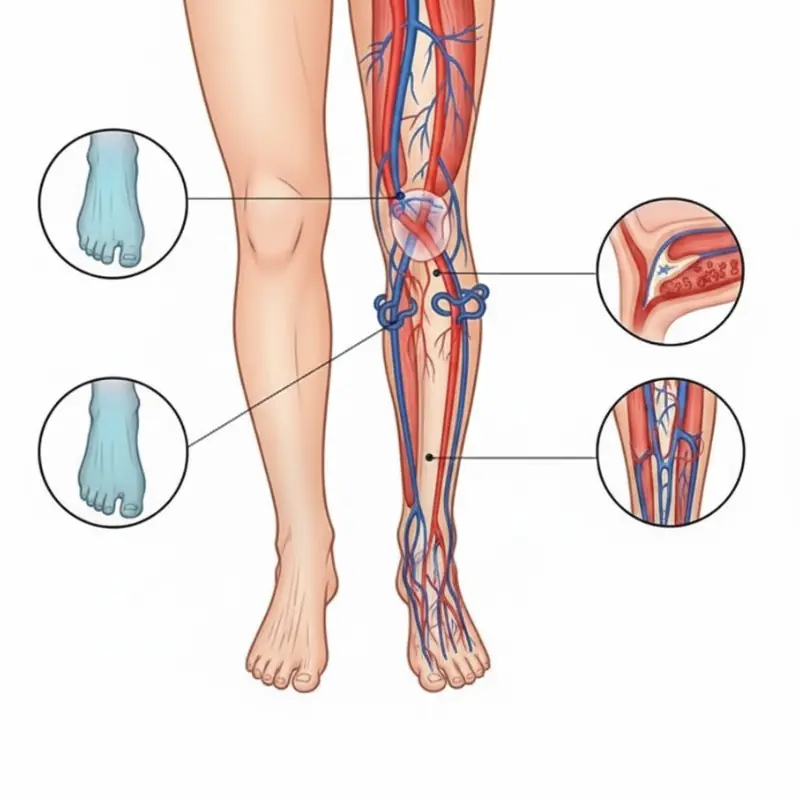

8 Tips to Improve Blood Circulation in Legs & Feet

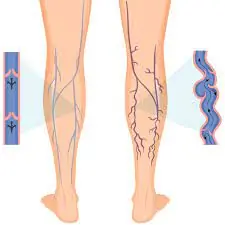

If You Have Poor Circulation, Cold Feet or Varicose Veins, Start Doing these 6 Things

When a Wife’s Intuition Speaks: Signs Your Husband May Be Having an Affair

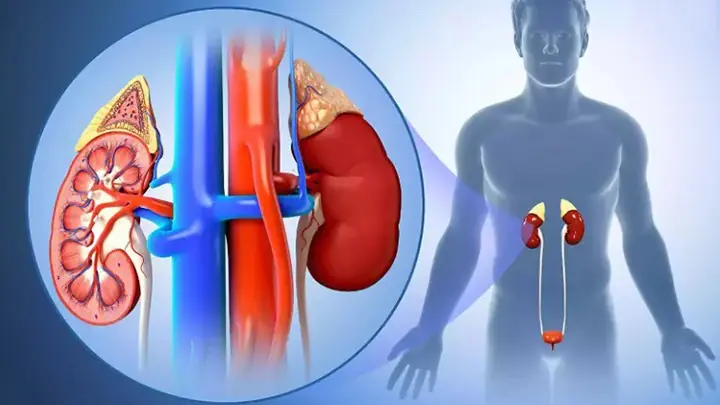

5 unusual foot symptoms that could signal kid.ney trouble

This food can solve many serious health problems - here's what you need to know

What causes night cramps and how to fix the problem

6 night-time warning signs of dia.betes you shouldn't ignore!

Kidney failure is silent, remember to do this to prevent it

Doctors Warn: This Common Way of Eating Boiled Eggs Can Clog Your Arteries

Ate food left in the fridge, 52-year-old man d.i.e.s: 6 foods you should never reheat

Doctors Recommend These 6 Things for Poor Circulation, Cold Feet, and Varicose Veins