We lost more than money when our business failed

We lost more than money when our business failed

The layout of our childhood home was a simple, three-bedroom ranch in the suburbs of Connecticut, but the emotional geography was as vast and treacherous as a mountain range. There were only twenty feet of hallway separating my bedroom from my sister’s, yet as I stand in that narrow corridor today, I realize we were raised on different continents, under different suns, governed by entirely different sets of laws.

My sister, Clara, was the golden child. I don't say that with the jagged bitterness I once possessed; I say it as a clinical observation of a fundamental truth. Clara was born with a natural, effortless grace—a girl who didn't just walk into a room but seemed to inhabit it as its rightful center. She was the one our parents, Sarah and Thomas, looked at when they needed a reason to believe the world was kind.

I, Leo, was the "sturdy" one. I was the child of footnotes and practicalities, the one who was expected to be self-sufficient because Clara required so much oxygen.

The favoritism wasn't a series of grand, dramatic slights; it was a slow-burning accumulation of small, quiet preferences. It was in the way my father’s voice took on a melodic, protective lilt when he spoke to her, a tone he never used with me. It was in the way my mother would spend hours helping Clara choose the perfect dress for a middle-school dance, while my own achievements—a second-place science fair trophy or a varsity letter—were met with a polite nod and a "That’s nice, Leo. Put it on the shelf."

I lived in a world of rules and consequences. Clara lived in a world of suggestions and exceptions.

I remember a Tuesday evening during my sophomore year of high school. I had come home fifteen minutes past my curfew because the bus had been delayed by a minor accident. My father met me at the door, his arms crossed, his face a mask of disappointment.

"Time is a reflection of character, Leo," he said, his voice cold. "If you can't respect the clock, you don't respect us. One week grounded."

I didn't argue. I went to my room, the silence of the house feeling like a physical weight.

An hour later, Clara floated through the front door, three hours late from a "study session" that I knew for a fact was a bonfire at the lake. I heard my father’s voice drift up the stairs. It wasn't cold. It was relieved.

"Clara, honey, you should have called. We were worried. Are you hungry? Your mother kept some chicken warm for you."

I sat on the edge of my bed, listening to the muffled sounds of their laughter in the kitchen. In that moment, the distance between my room and theirs felt like a thousand miles. I wasn't just in a different room; I was in a different reality. I was the son who was a "reflection of character," and she was the daughter who was simply "honey."

The slow-burning tension between Clara and me wasn't a product of our personalities—it was a product of the roles we had been forced to play. I looked at her with a quiet, simmering resentment, seeing her as the thief of the affection I craved. She looked at me with a vague, pitying confusion, unable to understand why I was always so "difficult" and "recessive."

We were two people sharing a bathroom and a dinner table, but we were strangers who spoke a language the other didn't know.

The emotional distance manifested in our adulthood. When we left for college, I moved to the furthest coast I could find, building a life out of spreadsheets and silence. Clara stayed close to home, becoming the social butterfly of the local community, the one who organized the holiday dinners and the "check-ins" that I rarely attended.

Every time I came home, the geography remained the same. My parents would spend thirty minutes talking about Clara’s new promotion or her latest charity work before asking me, as an afterthought, "And how is the weather in California, Leo?"

The "bittersweet understanding" didn't arrive with a grand apology or a sudden confession from our parents. It happened last winter, on the night before our father’s funeral.

The house was full of the heavy, floral scent of lilies and the hushed tones of grieving neighbors. Clara and I were in the kitchen, tasked with the mundane labor of organizing the Tupperware containers of casseroles that had been dropped off. The silence between us was the same one we had nurtured for thirty years—a wall of unspoken words.

I was being efficient, stacking the lids with a practiced, stoic precision. Clara was struggling, her hands shaking as she tried to find a match for a glass bowl. Suddenly, the bowl slipped from her fingers and shattered against the linoleum.

She didn't move. She didn't reach for a broom. She just stood there, looking at the shards, and began to cry. Not the loud, performative sob of a golden child seeking attention, but a quiet, broken sound that I had never heard from her before.

"I can't do it anymore, Leo," she whispered, her voice cracking. "I can't be the one who keeps everything together. I can't be the 'perfect' one today. I just want to be allowed to fall apart."

I looked at her, and for the first time in my life, the lens through which I saw her shifted.

I had spent my life envying her "sunshine," but I had never stopped to think about how exhausting it was to be the person who had to shine every single day. I had seen her as the thief of my parents' love, but I realized then that she was also its prisoner. She had been burdened with the weight of their expectations, forced to maintain a facade of effortless grace while I had been allowed the freedom of being "the sturdy one."

My parents didn't love her more; they loved her differently, and that difference had been a cage for both of us. They had looked to her for their happiness and looked to me for their stability. Neither of us had been seen for who we actually were.

I walked over and did something I hadn't done since we were toddlers. I pulled her into a hug.

"You don't have to be perfect, Clara," I said, my chin resting on the top of her head. "The roof isn't going to fall down if you break a bowl. I’m here. I’m the sturdy one, remember? I can handle the shards."

She leaned into me, her tears dampening my shirt, and the tension that had defined our relationship for three decades finally began to soften.

We grew up in the same house but different worlds, and we can't go back and fix the maps our parents drew for us. We can't erase the years of favoritism or the thousands of miles of emotional distance. But standing in that kitchen, surrounded by the remnants of a life that was both beautiful and broken, I realized that we don't have to live in those separate worlds anymore.

We are the Millers, the son of rules and the daughter of exceptions. We are flawed, we are hurt, and we are finally, quietly, siblings.

As we spent the rest of the night cleaning up the kitchen, we didn't talk about the science fair trophies or the missed curfews. We talked about the man we had both lost—the father who had loved us in a way that was as imperfect as the house we grew up in.

It’s bittersweet, knowing that we missed out on so many years of friendship because we were too busy guarding our own territories. But as I look at Clara now, sitting across from me with a tired smile, I realize that the geography of our family is finally changing. The hallway between our rooms is still twenty feet long, but for the first time in my life, I know exactly how to walk it.

We lost more than money when our business failed

The words i said in anger stayed with my son for years

I didn’t realize how lonely my mother was until it was almost too late

I thought my wife was keeping secrets but i was completely wrong

The old photo album brought our whole family together

I thought my marriage was ordinary until i looked closer

Our family road trip started with arguments and ended with laughter

My father never said ‘i love you,’ but he showed it every day

The day our power went out was the day we talked for hours

Moving in with my parents was supposed to be temporary

The surprise my kids planned changed the way i saw myself

We didn’t have much, but we always had sunday dinners

“You’ve been bleeding me dry for 38 years. From now on, every penny you spend comes from your own pocket!” he said. I just smiled. When his sister came for Sunday dinner and saw the table, she turned to him and said: “You have no idea what you had

At 69, I hired a private investigator just for “peace of mind.” He found my husband’s secret family and another marriage license from 1998. The detective looked at me and said, “Ma’am, you just became very rich.”

We left quietly, made one decision at a nearby café… and my phone soon showed 32 missed calls

We lost more than money when our business failed

The words i said in anger stayed with my son for years

I didn’t realize how lonely my mother was until it was almost too late

I thought my wife was keeping secrets but i was completely wrong

The old photo album brought our whole family together

I thought my marriage was ordinary until i looked closer

Our family road trip started with arguments and ended with laughter

My father never said ‘i love you,’ but he showed it every day

The day our power went out was the day we talked for hours

Guava leaves are not only an ingredient in cooking but also have many wonderful uses for health and beauty. Here are some of the outstanding benefits of guava leaves:

Here are 4 best vegetables that can help prevent cancer due to their rich content of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals:

Moving in with my parents was supposed to be temporary

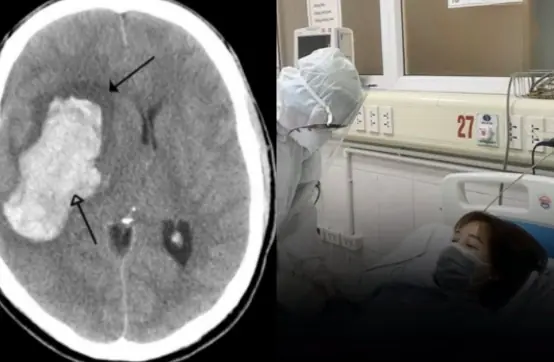

Even young individuals can experience strokes

The surprise my kids planned changed the way i saw myself

It’s fragrant, refreshing, and a staple in many Southeast Asian kitchens

We didn’t have much, but we always had sunday dinners

Oregano may seem like just another kitchen herb, but this small, fragrant leaf carries a surprising amount of medicinal power.

Boiled eggs are one of the most common and convenient foods in everyday life.

Although often praised as a “golden beverage” for its benefits to cardiovascular health, brain function, and energy metabolism, coffee is not always good for the body if consumed at the wrong time.