My mother-in-law criticized everything I did until the day we finally talked honestly

My mother-in-law criticized everything I did until the day we finally talked honestly

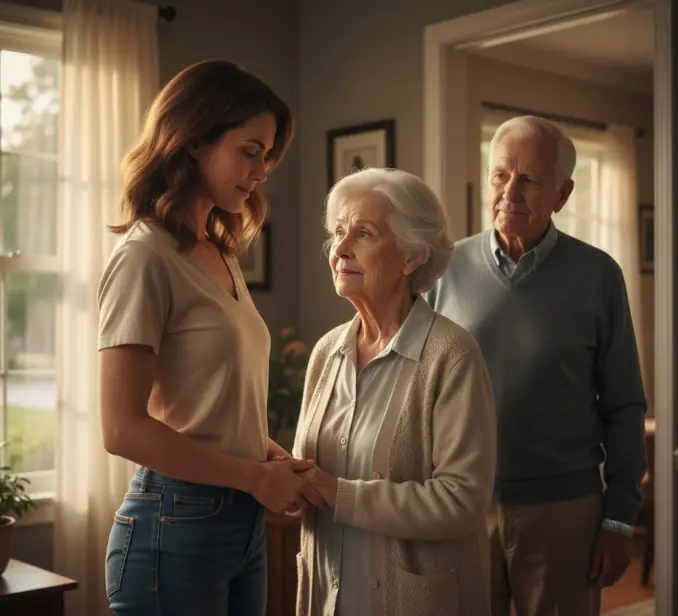

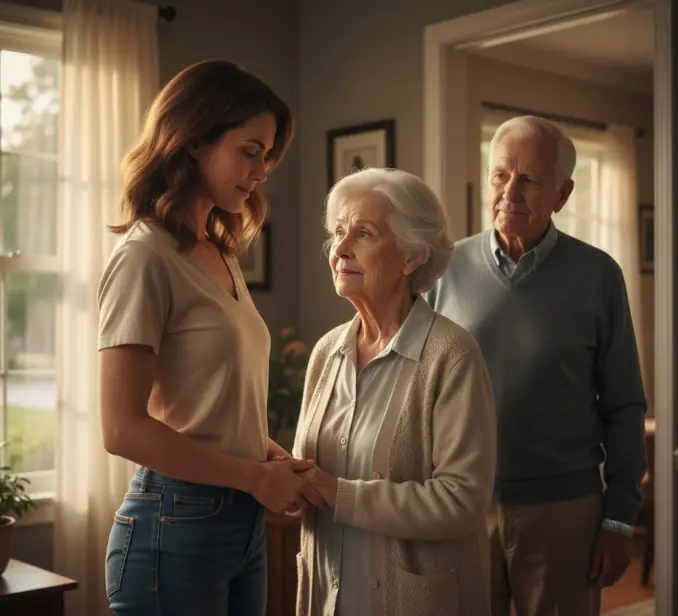

In the three years since I married Caleb, I had come to view Sunday dinners at my mother-in-law’s house as a weekly exercise in emotional endurance. Martha was a woman of iron-clad traditions and a home that smelled perpetually of lemon wax and pot roast. She was the kind of woman whose towels were always folded into perfect, identical rectangles and whose life was a series of checklists she had mastered decades ago.

I, on the other hand, was what Martha called "unstructured." I was a freelance graphic designer who worked from a desk covered in coffee rings and sketches. I believed in messy play for our two-year-old son, Leo, and I preferred quick, creative meals over the four-hour marathons Martha staged in her kitchen.

The tension wasn't loud. Martha never yelled; she spoke in the language of the "subtle suggestion," a dialect designed to point out my failures while maintaining a veneer of helpfulness.

"Oh, Diane, are you using store-bought pastry for the pot pie?" she would ask, her eyebrows arching just a millimeter. "I always found the homemade crust provides so much more... stability for the family. But I suppose we all have our priorities."

Then there was the parenting. If Leo had a smudge of dirt on his cheek, Martha was there with a damp cloth before I could even reach for a napkin. "Poor little thing," she’d coo, "it’s so important to keep their surroundings pristine, don't you think? It builds character."

Every comment felt like a tiny needle prick. By the time we’d reach the drive home, I would be vibrating with a mixture of resentment and inadequacy. Caleb, caught in the impossible crossfire, would try to play the diplomat.

"She doesn't mean it that way, Diane," he’d say, his hand resting on my shoulder. "She’s just... particular. She loves us."

"There’s a difference between loving someone and auditing them, Caleb," I’d snap back. "I feel like a guest in my own marriage when she’s around."

The emotional pressure cooker finally hissed toward a breaking point one Sunday in late October. We were at Martha’s for her birthday dinner. I had spent all morning trying to ensure Leo was perfectly dressed and that the gift I’d picked out—a delicate silk scarf—was wrapped with the precision of a professional.

But the afternoon was a minefield. Martha critiqued the way I held the carving knife, questioned why Leo wasn't in a more "formal" preschool program yet, and spent ten minutes explaining the "proper" way to load a dishwasher—a task I had apparently been failing at for thirty years.

I felt smaller with every passing hour. I felt like a shadow in a house built by a woman who viewed my presence as a series of errors to be corrected.

After dinner, while Caleb was outside showing Leo the turning leaves, I went into the kitchen to help with the coffee service. I stopped at the swinging door when I heard voices in the small sunroom just beyond. It was Martha and her sister, Aunt Joyce.

"She’s a lovely girl, Martha," Joyce was saying. "You should be happy Caleb found someone so bright."

There was a long pause, and then I heard Martha’s voice. It wasn't the sharp, confident tone I was used to. It was thin, brittle, and carried a tremor of something I didn't recognize.

"She is bright," Martha whispered. "But she’s so... independent. She has her own way of doing everything. Every time I see them, I feel like I’m being phased out. Caleb doesn't need my recipes anymore because she makes those quick wraps. He doesn't need my advice on the house because she has her 'vision.' I'm terrified, Joyce. If I don't show them the 'right' way to do things, what use am I to them? If I stop being the one with the answers, I’m afraid I’ll just be the woman they visit out of obligation until they eventually stop coming at all."

I stood frozen behind the door, the silver tray heavy in my hands. The realization hit me like a physical blow. I had seen her criticisms as an attack on my competence; she saw my competence as a threat to her existence. Her needles weren't meant to deflate me; they were her way of trying to stitch herself into our lives so she wouldn't fall out of them.

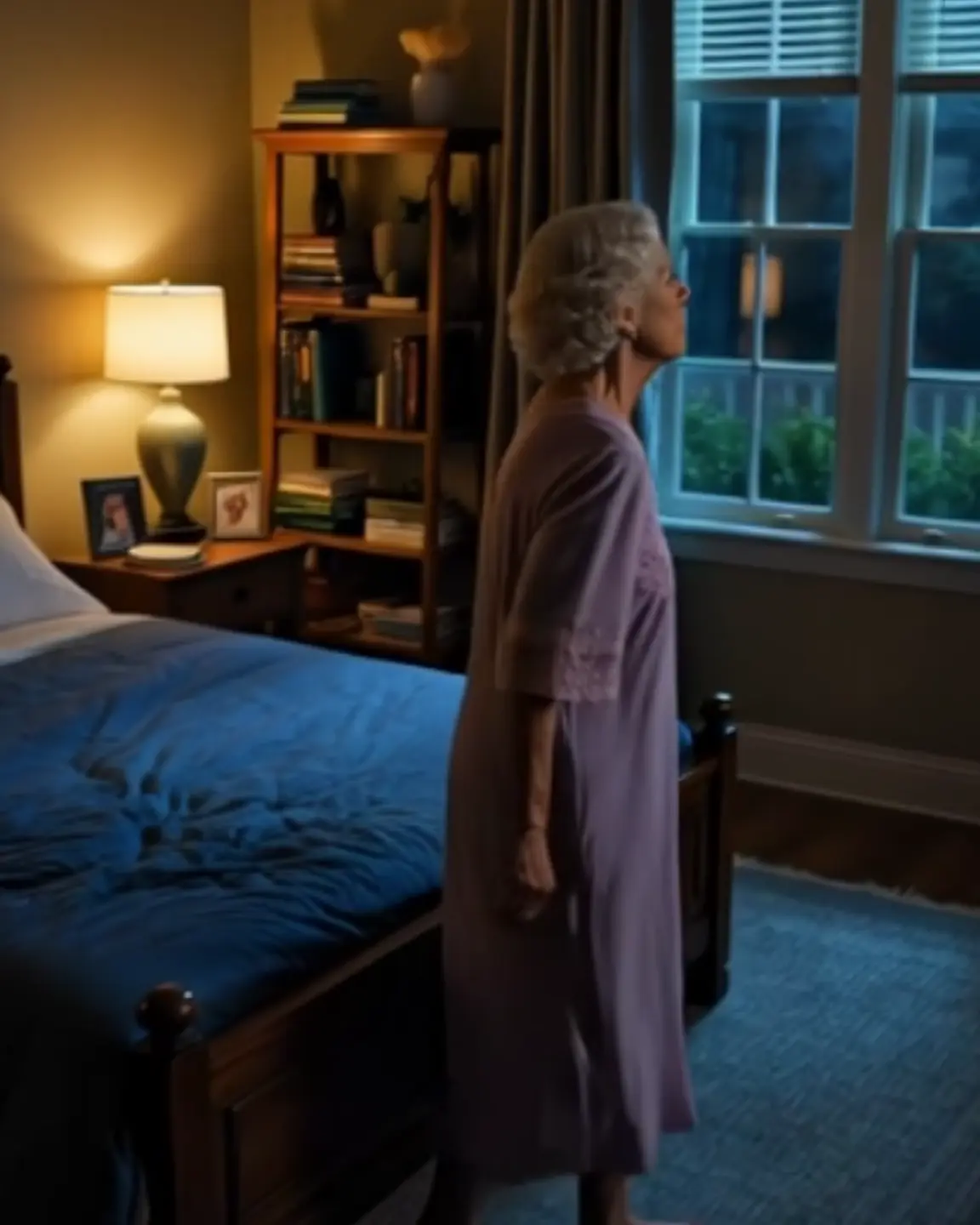

I waited until Joyce left to run an errand, then I pushed through the door. Martha was standing by the window, her back to me, dabbing at her eyes with a lace handkerchief.

"Martha?" I said softly.

She jumped, quickly straightening her apron and assuming her "inspector" posture. "Oh, Diane. I was just checking the seal on these windows. They’re a bit drafty."

"The windows are fine," I said, setting the tray down. I walked over and sat at the small bistro table. "Martha, I overheard what you said to Joyce."

The color drained from her face. She looked like a child caught in a lie. "I... I didn't mean to be dramatic, Diane. It’s just—"

"It’s okay," I interrupted, my voice steadier than I felt. "Can we just talk? Honestly?"

Martha sat down across from me. For the first time in three years, the "mother-in-law" mask was gone. In its place was a woman who looked tired and profoundly lonely.

"I’m sorry if I’ve made you feel like you’re being audited," I said, using the word I’d told Caleb. "But I need you to know something. I’m not trying to phase you out. I’m just trying to find my own feet. When you criticize the crust or the laundry, I don't hear 'help.' I hear that I'm not good enough for your son."

Martha’s eyes filled with tears again. "Oh, Diane. No. He adores you. That’s the problem. He looks at you the way he used to look at me—like you have all the answers. I’ve been 'The Mom' for thirty-five years. It’s the only thing I’m good at. If I’m not 'The Mom' who knows how to fix the pie or the child’s schedule, then who am I to him?"

"You're his mother," I said firmly. "That’s a permanent title. It doesn't depend on whether you make the pastry from scratch. We don't come here on Sundays because we need a tutorial on dishwashers. We come here because Leo loves his grandma and Caleb loves his mom. And I... I want to love my mother-in-law, but it’s hard to do that when I’m constantly defending myself."

We sat in silence for a long time. The afternoon sun cast long, golden shadows across the linoleum floor.

"I don't want to be a burden," Martha whispered.

"Then stop being a judge," I replied, reaching across the table to take her hand. Her skin was soft and papery, a map of a life spent caring for others. "Tell me stories instead of instructions. Tell me about Caleb when he was Leo’s age. Tell me what you were afraid of when you were a young mother. I don't need a teacher, Martha. I need a family."

The change didn't happen overnight, but the foundation shifted that evening. When we left, Martha didn't comment on the way Leo’s car seat was buckled. Instead, she gave me a hug that lasted a second longer than usual and whispered, "The scarf is beautiful, Diane. Truly."

Over the next few months, Sunday dinners became a different kind of ritual. We still ate pot roast, but I started asking Martha for her stories. I learned about her own mother-in-law, who had been even stricter than her. I learned about the lean years when she and my father-in-law had almost lost the house.

And slowly, Martha started to let go of the "checklist." One Sunday, I brought a salad I’d made with pomegranate seeds and kale—something Martha would have previously viewed as "suspicious greenery." She took a bite, nodded, and said, "This is very refreshing, Diane. You'll have to show me how you dressed it."

It was a small victory, but it felt like a triumph.

We are the Millers, and we are still a work in progress. Martha still occasionally mentions that the towels could be fluffed more effectively, but now, instead of bristling, I just smile and say, "I’ll keep that in mind, Martha." And she smiles back, knowing that I probably won't, and that it’s okay.

I’ve learned that most criticism isn't about the person receiving it; it’s about the person giving it. It’s a shield for their own fears. And Martha has learned that she doesn't have to be perfect to be essential.

Love doesn't require a perfectly folded rectangle or a homemade crust. It just requires the courage to be vulnerable and the grace to listen. Our Sundays are no longer an endurance test; they are a homecoming. And as I watch Martha sitting on the rug, helping Leo build a "messy" tower of blocks, I realize that we didn't just save our Sunday dinners. We saved each other.