7 Foods With Anticancer Effects You’ve Probably Never Heard About

7 foods with anticancer effects you probably didn’t know about.

7 foods with anticancer effects you probably didn’t know about.

Struggling with low energy or constant fatigue? While many factors can contribute to feeling this way, certain natural ingredients may support your daily energy levels.

Rice Water: How to Turn Cloudy Rinse Water into a Natural Beauty Boost for Skin and Hair

Yellow teeth? Try this viral hack before your next dental visit.

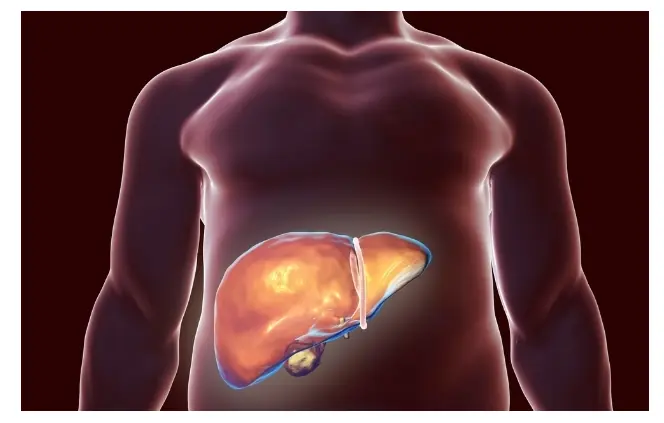

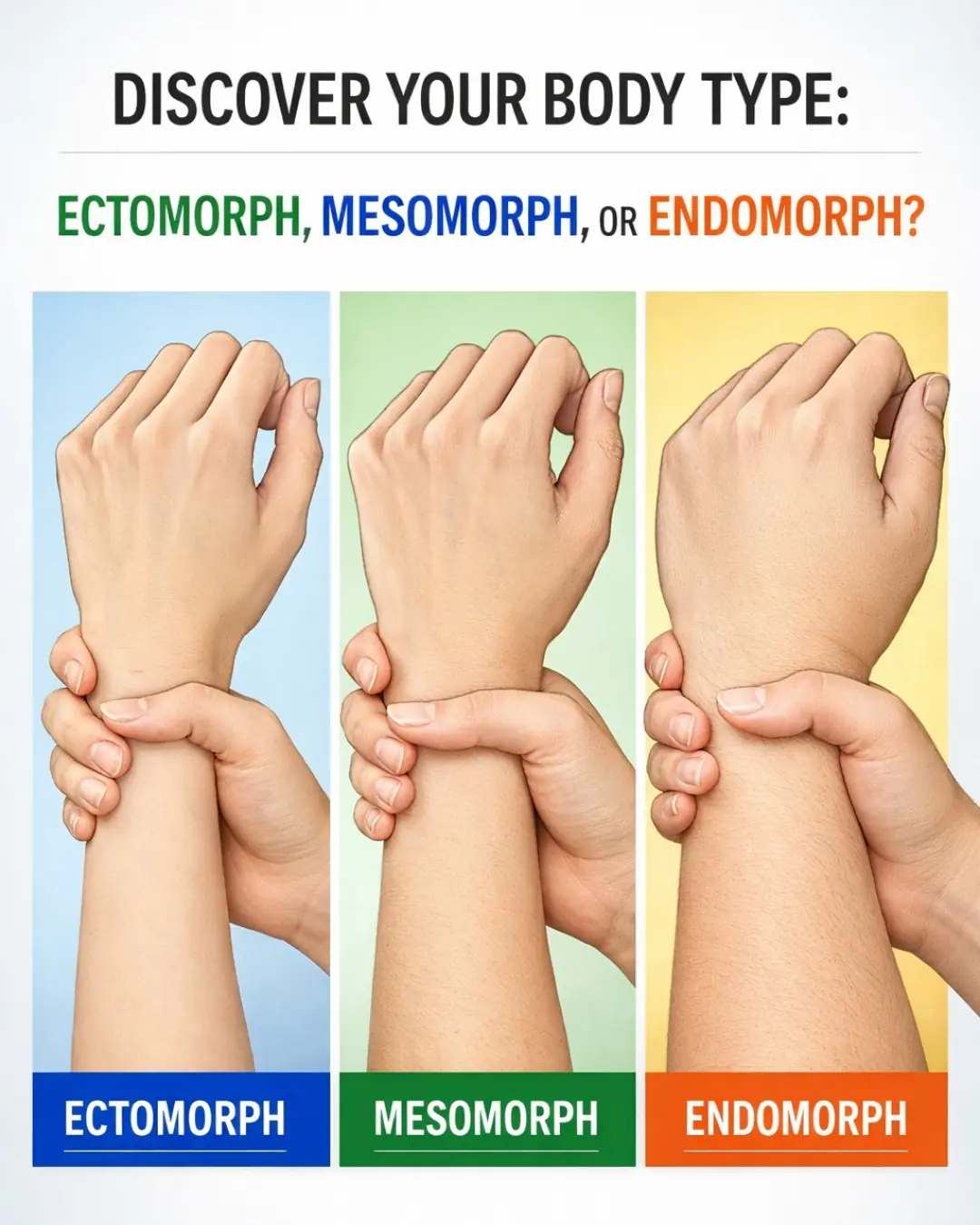

Ectomorph, Mesomorph, or Endomorph? Discover Your True Body Type

The Hidden Health Risks of Poor Sleep Posture (And How to Correct Them)

7 must-know tips for using cloves effectively

Researchers outline 7 hidden health problems your nails might suggest

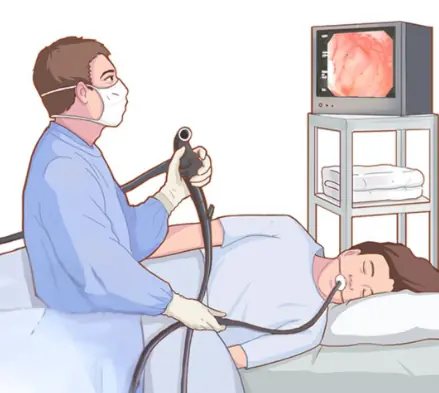

For many people, simply hearing the word “colonoscopy” is enough to cause immediate fear or discomfort.

Peanuts, also known as groundnuts, are rich in vitamins and nutrients, often hailed as a "longevity nut" that is highly beneficial for health.

Occasionally noticing foamy urine is usually harmless and not a cause for concern.

Heart disease does not always announce itself with dramatic chest pain during the day. In many cases, the heart sends subtle warning signals at night, when the body is at rest and symptoms become more noticeable.

Have you ever noticed a faint hum, buzz, or ringing in your ear — especially when everything around you is silent?

When our skin becomes itchy, we often attribute the discomfort to external factors such as sweat, hygiene products, laundry detergents, or the fabric of our clothing.

tching is a common condition that everyone experiences, and it is usually not a serious sign.

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) is one of the most studied and respected medicinal plants in modern herbal medicine.

Understanding Persistent Tinnitus and When to Seek Care

Waking up with a dry mouth may feel like a small inconvenience, but it can actually be your body’s subtle way of raising a warning sign.

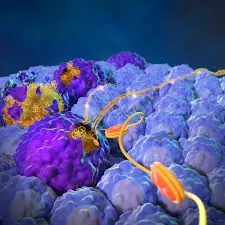

Kidney failure is a serious condition that can lead to lifelong dialysis or other severe health complications if left untreated.