I was ashamed of my mom’s old car until the night it saved my dad

I was ashamed of my mom’s old car until the night it saved my dad

The wood of the dining table is a dark, polished cherry, scarred by decades of family dinners, homework marathons, and the occasional spilled glass of wine. For twenty years, that table was the anchor of our home, a solid rectangular continent where the four of us gathered to map out our lives. But tonight, as the steam rises from a bowl of mashed potatoes and the late autumn wind rattles the windowpane, the table feels less like a continent and more like a vast, empty sea.

At the far end, across from where I sit, there is a chair. It is a simple wooden chair with a slightly wobbling left leg and a cushion that has flattened over time. It is empty.

In our house, the absence of my younger brother, Caleb, is not a sudden tragedy or a cinematic vanishing. It is the result of a slow, quiet drift—the kind of distance that builds up like silt in a river until the path is no longer navigable. Two years ago, Caleb left for a job on the other side of the country, fueled by a restless energy I never quite understood and a lingering tension with our father that neither of them ever found the words to resolve.

He didn't leave in a storm of shouting; he left in a series of boxes and a polite, guarded handshake at the airport. Now, he is a face on a flickering screen once a month and a voice that sounds increasingly like a stranger’s on the telephone.

The empty chair at the table says more than his letters ever could. It speaks of the jokes that go uncracked, the arguments that have no one to finish them, and the peculiar, hollow ache of a family that has become a triangle when it was built to be a square.

I remember the dinners of my childhood as a symphony of noise. Caleb was the percussion—constantly drumming his silverware against the placemat, restless and vibrant. He was the one who would tell a story so ridiculous that my mother would forget to scold him for not eating his peas. He was the one who challenged my father’s stoic opinions, sparking debates that lasted long after the plates were cleared.

That chair used to hold a person who filled the room with a chaotic, beautiful light. Now, it holds only the shadow of what we used to be.

My mother, Martha, still sets the table with four placemats. It is a habit she refuses to break, a quiet ritual of hope that she performs every evening at 6:00 PM. She lays out the forks and knives with a meticulous, trembling precision, as if the right arrangement of silver might act as a magnetic pull, drawing her son back across the three thousand miles of mountain and prairie.

"He called today," she says, her voice carefully neutral as she passes me the salad tongs. "He says the weather in Seattle is turning cold."

"That’s good, Mom," I reply, my voice mirroring hers. "He always liked the rain."

We avoid looking at the chair. We treat it like a sovereign nation that requires a passport we no longer possess. We talk around it, our conversation a series of bridges built over a canyon of longing. We talk about the neighbors, the news, and the upcoming holidays, but we do not talk about the fact that the mashed potatoes are too much for three people, or that the house feels unnervingly quiet without the sound of Caleb’s boots hitting the floorboards.

The longing is a physical thing. It’s a phantom limb that itches in the middle of a meal. I find myself looking toward his chair when I have a piece of news—a promotion at work, a funny observation about a coworker—only to be met with the sight of the dark cherry wood and the flattened cushion. The silence that follows is a sharp, stinging reminder that the person who would have laughed the loudest is no longer here to hear it.

I think about the memories that are embedded in that wood. There is a small, jagged scratch near the corner where Caleb tried to carve his initials when he was seven. There is a faint ring from a coffee mug he left there the morning he moved out. These are the artifacts of a life shared, the tiny, indelible marks of a brotherly bond that I took for granted for so long.

I used to be the "serious" one, the elder sister who found his restlessness exhausting. I spent years wishing he would just sit still, just be quiet, just let us have a peaceful meal. Now, I would give anything for a single evening of his silverware drumming and his ridiculous stories. I realized too late that the "peace" I wanted was actually just a precursor to this loneliness.

The acceptance began to settle in during the first snowfall of this year.

I was in the kitchen, helping my mother dry the dishes. The house was filled with the smell of cinnamon and the soft hum of the radio. My father was in the living room, reading a book, his silhouette framed by the amber glow of the lamp. It was a scene of perfect, domestic stability, yet the empty chair was still there, visible through the doorway.

"He’s not coming back for Christmas, is he?" I asked softly, hanging the damp towel on the oven handle.

My mother stopped scrubbing a pot. She didn't look up, but her shoulders slumped just a fraction. "He said the flights are too expensive. And he has to work the day after."

"He’s building a life, Mom," I said, the words feeling heavy in my mouth. "A real one. Without us."

She finally looked at me, and I saw the reflection of my own grief in her eyes. It wasn't the jagged grief of death; it was the soft, persistent grief of change. It was the realization that our roles had shifted. We were no longer the caretakers of his daily life; we were the keepers of his history.

"I know," she whispered. "I just keep waiting for the chair to move. I keep waiting to hear the back door slam and see him sitting there, complaining about the carrots."

In that moment, the weight of the silence changed. It stopped being a burden and started being a space for understanding. I realized that Caleb’s absence wasn't a failure of our family; it was a testament to the fact that we had raised him to be strong enough to leave. The distance wasn't a wall; it was a horizon he was exploring.

We walked into the dining room together. My mother reached out and touched the back of the empty chair, her fingers tracing the wood. She didn't cry. She just nodded once, a quiet gesture of surrender to the reality of time.

"Tomorrow," she said, her voice steadying, "I’m only going to set three places. Not because he isn't loved, but because he isn't here. And that has to be okay."

It was a small act of quiet emotional strength, a refusal to live in a museum of "what used to be."

The next evening, the table looked different. The symmetry was gone, and the dark cherry wood was more visible where the fourth placemat used to be. It was jarring at first, a visual stutter in our routine. But as we sat down to eat, something happened. Without the "ghost" of the fourth person at the table, the three of us began to speak more clearly.

We didn't talk around the absence anymore. We talked about Caleb—the real Caleb, the one who was currently three thousand miles away, probably eating a sandwich over a sink and thinking about the rain. We shared the old stories not as mourning rituals, but as celebrations. We laughed at the car-carving incident and the science project that exploded in the garage.

The empty space at the table didn't disappear, but it stopped being a canyon. It became a window. We looked through it and saw a brother and a son who was out in the world, living the life we had prepared him for.

I am Clara, and I am the sister of a man who is a horizon away. I still miss the drumming of the silverware and the ridiculous stories. I still feel the phantom itch of his presence when the room gets too quiet. But as I look at my parents across the dark cherry wood tonight, I feel a new kind of solidity.

We are a triangle now, and that is a sturdy shape. We are smaller, but we are intentional. We have accepted the silence, and in doing so, we have found a way to hear each other again. The empty chair is gone, replaced by the vast, open space of the future. And as I pick up my fork, I realize that love doesn't require a physical seat at the table to be felt. It is the wood itself. It is the meal. It is the strength to let go and the courage to stay.

I am Leo's sister, and I am finally at peace with the quiet.

As the season turns and the days grow shorter, the memory of that empty chair remains a part of the house, but it no longer defines the room. We have learned to carry the absence without letting it crush us. And in the quiet of the evening, when the wind rattles the glass, I find myself looking at the dark cherry table and seeing not what is missing, but what remains—the three of us, steady and whole, under a roof that is still full of love.

I was ashamed of my mom’s old car until the night it saved my dad

I almost sold my late father’s house to a stranger — until my son asked me one question that changed everything

We pretended everything was fine until it wasn’t

I thought my parents were strong until i saw them break

My sister and i grew up in the same house but different worlds

We lost more than money when our business failed

The words i said in anger stayed with my son for years

I didn’t realize how lonely my mother was until it was almost too late

I thought my wife was keeping secrets but i was completely wrong

The old photo album brought our whole family together

I thought my marriage was ordinary until i looked closer

Our family road trip started with arguments and ended with laughter

My father never said ‘i love you,’ but he showed it every day

The day our power went out was the day we talked for hours

Moving in with my parents was supposed to be temporary

The surprise my kids planned changed the way i saw myself

We didn’t have much, but we always had sunday dinners

Home remedies to remove tartar dental

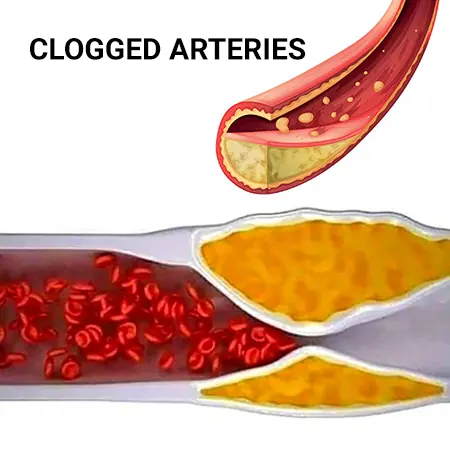

Clogged arteries rarely happen overnight. Instead, they develop slowly as fat, cholesterol, and other substances build up inside blood vessels, a process known as atherosclerosis.

10 signs that a man shows when he's in love

I was ashamed of my mom’s old car until the night it saved my dad

I almost sold my late father’s house to a stranger — until my son asked me one question that changed everything

We pretended everything was fine until it wasn’t

I thought my parents were strong until i saw them break

Managing blood sugar does not have to rely solely on medication or strict dietary deprivation.

Broccoli has earned its place as one of the healthiest vegetables on the planet — and for good reason.

When you have to be at work bright and early the next morning, it’s extremely unpleasant to wake up at an ungodly hour and find yourself unable to get back to sleep.

Kidney stones are one of the most common urinary stone disorders, especially among middle-aged men.

My sister and i grew up in the same house but different worlds

We lost more than money when our business failed

The words i said in anger stayed with my son for years

I didn’t realize how lonely my mother was until it was almost too late

I thought my wife was keeping secrets but i was completely wrong

The old photo album brought our whole family together

I thought my marriage was ordinary until i looked closer

Our family road trip started with arguments and ended with laughter