What are the symptoms of no.seble.eds and when should you see a doctor?

1. What disease is a nosebleed a symptom of?

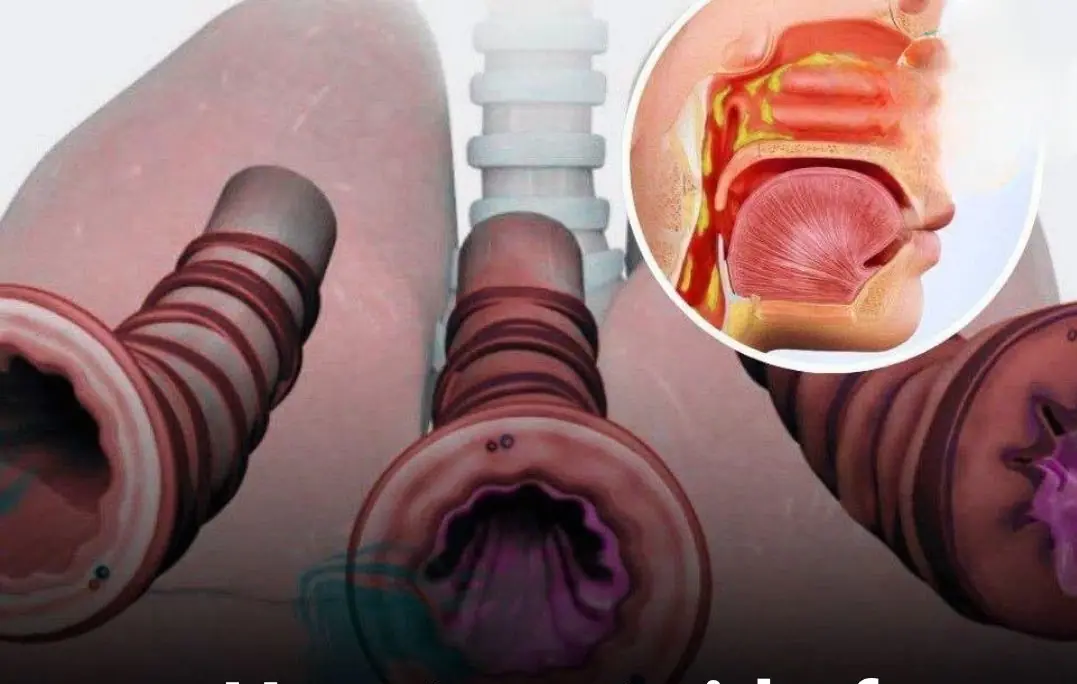

Nosebleeds are a condition of nosebleeds when the capillaries in the nose are broken for some reason, causing blood to flow out. In most cases, this symptom is not dangerous, the condition is not serious and can be treated with common first aid.

Nosebleeds due to ruptured blood vessels in the nose

Whether a nosebleed is a symptom of a disease depends on the type of bleeding and the amount of blood. If nosebleeds are frequent and severe, it can be a sign of many dangerous diseases or complications such as:

1.1. Cardiovascular disease, blood pressure

Patients with high blood pressure often experience nosebleeds. The cause is when blood pressure increases suddenly, causing damage and rupture of blood vessels in the nose. In particular, if high blood pressure is combined with arteriosclerosis, it can cause elderly patients to bleed heavily with large volumes and frequently. Be careful if you have high blood pressure, avoid strenuous exercise, injuring the nose or constipation and straining because it can easily cause blood vessels to rupture and nosebleed.

1.2. Blood disorders

Nosebleeds can originate from blood disorders such as: Blood clotting disorders, changes in platelet count, etc. In addition, side effects of anticoagulant drugs also cause frequent nosebleeds.

1.3. Benign fibroids

Benign fibroids in the nasopharynx, nasal cavity or tumors invading the oculomotor nerve can cause symptoms of nosebleeds, blurred vision, weak constitution, pale skin, etc. When these suspicious symptoms appear, patients should go to a medical facility for examination and testing to accurately diagnose the location and size of the tumor. Benign fibroids usually do not develop into malignancy or pose a risk of cancer, but surgery is still required to remove them.

The tumor's invasion of nerves, causing nosebleeds and other systemic symptoms, warns of the dangerous level of the disease.

1.4. Cancerous fibroids

Malignant fibroids in nasopharyngeal cancer cause the initial sign of frequent nosebleeds, along with symptoms such as ulcers and chronic nasopharyngeal inflammation as the disease progresses. When nosebleeds appear with other suspicious signs, the patient needs to go to a medical facility for examination and diagnosis.

In addition, nosebleeds can be caused by ethmoid cancer, but are less common.

1.5. Acute infectious fever

When suffering from acute fever, measles, scarlet fever, etc., blood vessels in the nasal mucosa are also easily dry and damaged. At that time, if there are some slight impacts such as sneezing, blowing your nose, wiping your nose, etc., it can easily cause rupture and bleeding.

1.6. Rhinitis

The nasal cavity is an area that is susceptible to inflammation, causing diseases such as rhinitis, sinusitis, etc. Nosebleeds are a common symptom of these diseases.

1.7. Nasal cavity trauma

The reason for frequent nosebleeds can also be due to strong impact injuries to the nasal cavity such as:

- Trauma due to treatment of head and neck diseases: Nosebleeds combined with symptoms of edema and rhinitis.

- Barotrauma due to pressure difference: Often occurs when sitting on an airplane or diving, the difference in external pressure and pressure in the nasal cavity is so large that the body cannot adapt in time, blood vessels are also easily dilated and bleed.

1.8. Other diseases

Some diseases can also cause nosebleeds but are less common, such as:

- Liver diseases.

- Rheumatism.

- Liver diseases.

- Kidney failure.

It can be seen that nosebleeds can also originate from dangerous diseases and complications. Therefore, when patients experience this symptom frequently, large amounts of bleeding, and other health signs, they should go to a specialized medical facility for examination and treatment.

2. When should you see a doctor for nosebleeds?

Most cases of nosebleeds are not too dangerous to health and life, however, if you experience heavy bleeding that cannot be controlled, you should go to the hospital immediately, such as:

- Nosebleeds with trauma to the nose causing pain and swelling.

- Nosebleeds due to head trauma, with or without symptoms of headache, still need to be examined.

- Nosebleeds that do not stop even after 20 minutes of emergency medical care.

- Broken nose due to trauma.

- Frequent nosebleeds, repeated many times.

- Nosebleeds with headaches, dizziness, prolonged nausea.

- Patients with blood clotting disorders, undergoing chemotherapy or using anticoagulant drugs such as aspirin, warfarin, ...

If the bleeding is too much and cannot be stopped, it can cause anemia, fatigue, dizziness, lightheadedness or fainting. In addition, if nosebleeds are related to cardiovascular disease, blood pressure, especially sudden changes in the environment, it can cause stroke and death. Therefore, do not ignore even the smallest signs of health and illness in the body.

News in the same category

A 41-Year-Old Woman Discovers Sto.mach Can.cer from Digestive Symptoms Many People Often Overlook

People with Colorectal Can.cer Often Share 4 Habits — Hopefully You Don’t Have Any of Them

Put eggshells in a pan to dry roast, many great uses, save a lot of money

11 Reasons Why You Have Red Dots On Your Skin

The 5 Best Nutrients to Reduce Swelling in the Feet and Legs

Indoor Air Quality: 6 Common Household Items That May Affect Your Lungs — And How to Use Them Safely

3 Vegetables That Support Cancer Prevention — Backed by Science

Leg Cramps at Night: Causes, Prevention & Treatment

The Ten Foods You Should Start Eating Now to Cleanse Your Colon

5 Signs Your Lungs are Being Exposed to Mold

4 alarming symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency you can’t ignore!

Why You Wake Up to Pee at Night (and How to Stop It for Good!)

3 Ways to Stop Acid Reflux Naturally

Thankfully, there are several things you can do at home to help clear mucus and breathe easier

Most cases of stomach can:cer are detected too late.

Intestinal polyps often show 4 signs when you go to the toilet — act before it reaches the final stage

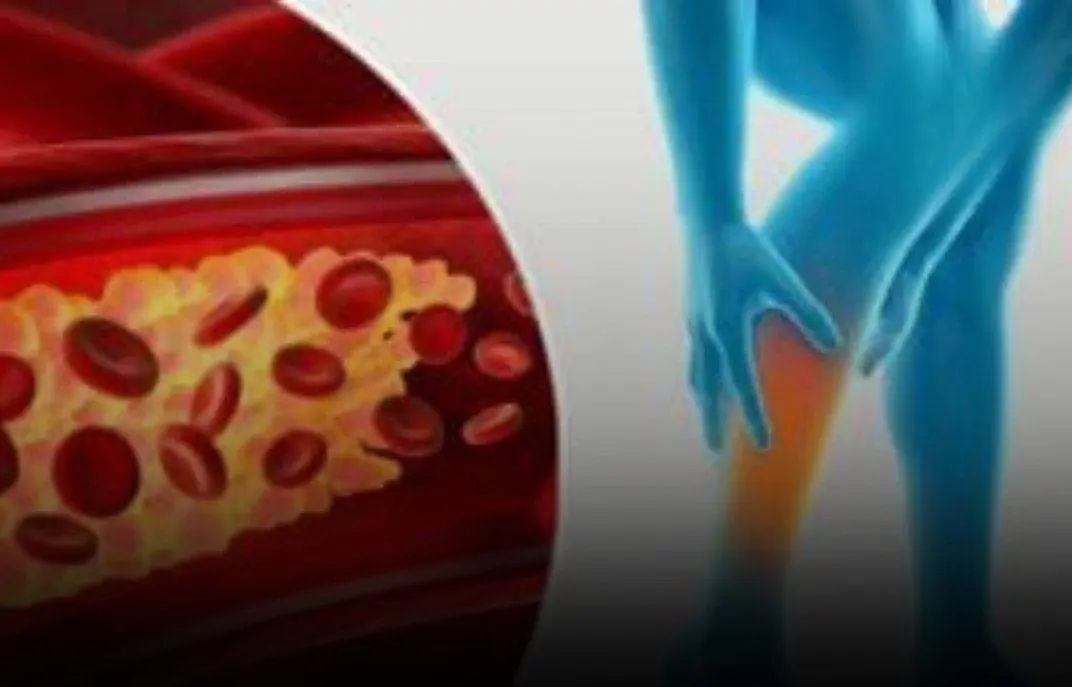

Your feet could be signaling that your arteries are clogged.

Avoid these drinks before bedtime — they could keep you tossing and turning all night!

Your body may be signaling can:cer with these 5 hidden warning signs

News Post

Can.cer Doesn’t Happen by Chance: 3 Foods That Quietly Fuel Malignant Cells

A 41-Year-Old Woman Discovers Sto.mach Can.cer from Digestive Symptoms Many People Often Overlook

People with Colorectal Can.cer Often Share 4 Habits — Hopefully You Don’t Have Any of Them

Put eggshells in a pan to dry roast, many great uses, save a lot of money

11 Reasons Why You Have Red Dots On Your Skin

The 5 Best Nutrients to Reduce Swelling in the Feet and Legs

Indoor Air Quality: 6 Common Household Items That May Affect Your Lungs — And How to Use Them Safely

3 Vegetables That Support Cancer Prevention — Backed by Science

Leg Cramps at Night: Causes, Prevention & Treatment

Proven Foods, Supplements and Vitamins That Act as Powerful Natural Blood Thinners

The Ten Foods You Should Start Eating Now to Cleanse Your Colon

5 Signs Your Lungs are Being Exposed to Mold

4 alarming symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency you can’t ignore!

Why You Wake Up to Pee at Night (and How to Stop It for Good!)

3 Ways to Stop Acid Reflux Naturally

Thankfully, there are several things you can do at home to help clear mucus and breathe easier

Most cases of stomach can:cer are detected too late.

Intestinal polyps often show 4 signs when you go to the toilet — act before it reaches the final stage

Your feet could be signaling that your arteries are clogged.