Tsunami and its warning signs, essential for those who often go to sea

Tsunamis: One of Nature’s Fiercest Phenomena

Tsunamis are among the most extreme natural phenomena that Mother Nature sends to Earth. In the past, they have claimed countless lives, destroyed homes, swept away everything in their path, and left behind devastation once the waters recede.

What Is a Tsunami?

A tsunami is a series of large ocean waves caused by the displacement of the Earth's crust beneath the ocean. This displacement can result from earthquakes, the fracturing of tectonic plates, continental shelf collapses, massive underwater landslides, or volcanic eruptions beneath the sea.

In the Earth's long history, even meteorites crashing into the ocean have caused tsunamis. In general, any seismic activity or powerful vertical force acting upward from a depth of over 50 meters under the sea can trigger a tsunami.

The Japanese coined the term “harbor wave” to describe tsunamis because historically, they observed large waves originating from the open sea without knowing whether they were regular ocean waves or something far more dangerous. From afar, a tsunami may resemble regular large swells—only slightly taller and longer.

It’s only as these waves near the shore that their true nature becomes clear. Tsunamis were once mistakenly referred to as “tidal waves,” but this term has long been rejected. Tides and normal waves are influenced by wind and the moon’s gravitational pull. In contrast, tsunamis do not rely on wind or Earth’s natural satellite. They are caused by a sudden, powerful vertical force from deep within the ocean.

How Are Tsunamis Formed?

When the Earth’s crust shifts beneath the sea—due to volcanic eruptions, landslides, or tectonic movements—it can trigger an undersea earthquake. This shift creates immense upward pressure on the water above, causing waves to rise and spread farther than usual. Typically, earthquakes registering 6.0 or higher on the Richter scale can generate tsunamis.

Think of dropping a rock into a pond. As it sinks, the downward force creates concentric ripples on the surface. A tsunami is similar: a massive underwater disturbance displaces a vast volume of water, which surges upward and spreads outwards due to gravity. The radius of a tsunami can span more than 1 kilometer.

The enormous energy traveling upward from the ocean floor propels the tsunami at remarkable speeds—between 500 to 800 km/h. As it nears the shore and encounters shallower waters, it transforms into a series of “shallow water waves.” At this point, the wave slows to 35–70 km/h, compresses, and rises dramatically, reaching heights of several meters or even tens of meters before crashing onto the land.

Historical Evidence of Tsunamis

In 479 BC, during the Persian siege of the Greek city of Potidaea, the tide receded unusually far, opening a path for the Persians to attack. Believing the gods had blessed them, the Persian soldiers charged forward—only to be swept away by an immense wave. The locals believed the god Poseidon had saved them, but in fact, it was a tsunami.

Though often mistaken for tidal waves, tsunamis have nothing to do with tides. Unlike regular waves driven by wind, tsunamis are energy waves that move through water. Their energy comes not from the atmosphere, but from the ocean’s depths.

When tectonic plates shift, underwater volcanoes erupt, or landslides occur, immense energy is released, displacing seawater and forming tsunamis. This force causes water to rise above sea level, but gravity quickly spreads the energy outward, creating massive, fast-moving waves.

From the deep ocean, tsunamis are nearly undetectable, moving silently under the surface. As they approach shallow coastal waters, their energy compresses, slowing the wave and dramatically increasing its height—sometimes up to 30 meters.

Upon landfall, a tsunami can pull the sea far away from the shore, deceive onlookers, and then return with devastating force. It can drown people, level homes, uproot trees, and leave behind destruction and grief.

Governments try to mitigate tsunami damage with seawalls and canals. However, these aren’t always effective. In 2011, a tsunami overwhelmed the sea wall protecting the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan, killing over 18,000 people and triggering a nuclear crisis.

The Danger and Warning Signs of a Tsunami

In deep waters, a tsunami might only be 1 meter taller than a regular wave, making it nearly impossible for fishermen or swimmers to detect. Only when it reaches shore does it rise dramatically—sometimes dozens or even hundreds of meters—too late for most to escape.

Compared to hurricanes, which cause ocean levels to rise about 10 meters at most, a tsunami’s height can dwarf even the mightiest storm. Some historical tsunamis have reached several hundred meters in height.

In densely populated coastal areas, this is a true catastrophe. A tsunami is a monstrous force of water that can obliterate everything in its path, with a destructive radius over 1 kilometer.

Numerous deadly tsunamis have been recorded in history as reminders of nature’s destructive power. Unlike storms, which can be predicted days in advance, tsunamis can arrive within minutes of initial warning signs.

While some nations have developed early-warning systems, people can also watch for the following signs:

-

Earthquakes near coastal areas: If you feel shaking near the sea, a tsunami may follow—there’s a 90% chance.

-

Foamy or bubbling seawater: If the ocean suddenly appears fizzy, smells like gasoline or rotten eggs (due to hydrogen sulfide), or feels unusually warm, these are signs of seismic activity below.

-

Unexplained loud noise from the sea: It could sound like a blast or an eerie whistling.

-

Dark clouds and red light on the horizon: Unusual atmospheric conditions may accompany an approaching tsunami.

-

The sea suddenly recedes: This is the “trough” of the wave pulling back to build force. If you see this, run immediately. Some people have mistaken this for a curiosity and wandered into the exposed seabed—only to be swept away moments later.

-

Loud roaring similar to a train whistle: When the wave crashes, it sounds like a siren or train. If you see water reaching even halfway up a building, you are in grave danger.

-

Animal behavior: Some birds, especially seagulls, can sense infrasound from under the sea. If they suddenly fly inland or back to sea, take it as a warning and evacuate.

Tsunamis That Made History

-

July 9, 1958 – Lituya Bay, Alaska: A magnitude 8+ earthquake triggered a landslide that sent 40 million cubic meters of rock from 900m high into the sea, producing a 527-meter-high tsunami—the tallest ever recorded.

-

May 1960 – Chile: A 9.5 magnitude earthquake—the strongest in recorded history—created a tsunami that killed over 5,700 people, reaching as far as Hawaii and Japan, where nearly 200 more perished.

-

August 17, 1976 – Philippines: A 7.9 magnitude earthquake triggered a 5-meter tsunami that killed nearly 8,000 people in their sleep.

-

July 17, 1998 – Papua New Guinea: Twin earthquakes (7+ magnitude) created a tsunami that took 6,000 lives.

-

December 26, 2004 – Indian Ocean: A 9.0+ magnitude earthquake led to one of the deadliest tsunamis in modern history, killing 220,000 people across multiple countries. Indonesia alone lost over 170,000 lives.

-

March 11, 2011 – Japan: A 9.0 magnitude earthquake created a tsunami that killed over 25,000 people and led to the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

How to Respond When a Tsunami Is Approaching

If a tsunami warning is issued—or if you recognize the signs—immediate evacuation is the only priority. Low-lying coastal areas will be inundated first, so do not stay at the beach, in houses, or on streets below elevated land. If warned in time, head to the hills or inland several kilometers.

If you’re near tall buildings, head to the upper floors (above the third floor). Carry only essential documents and valuables—travel light to move faster.

Boats should head to deeper waters away from shore, not back to port. Tsunamis can violently change sea levels, endangering vessels near land. If already at port, get off the boat and head to high ground immediately.

Countries in earthquake-prone zones must invest in strong sea defenses at least 10 meters high and implement modern tsunami detection systems. Coastal regions should also have visible evacuation routes.

Important Fact: A tsunami typically lasts more than an hour and may arrive in multiple waves—each larger than the last. They are spaced about 30–45 minutes apart. Do not return to the coast after the first wave—it is likely just the beginning.

Nature gives life—and sometimes takes it. Learning how to coexist with these hazards is essential. While humans cannot always overcome nature’s power, we can build global information systems to detect and respond quickly. Each person must also understand the specific risks of their region, so when disaster strikes, they are prepared to survive.

News in the same category

Reasons you should not ki.ll millipedes

When A Brown Bug Like This Appears In Your Yard, Immediate Action Is Required

Tips for washing grapes to remove dirt and worm eggs, and to safely eat the skin

Don’t Eat Grapes Before You Know This Trick

No Matter How You Wash Clams, There’s Still Grit Inside?

The Secret to Keeping Potatoes Fresh for 6 Months Thanks to a Surprising “Friend” in the Kitchen

Unusual moles might be more than just a skin quirk — they could be warning signs of cancer

Using the Air Conditioner and Fan at the Same Time? I Expected Higher Costs, but the Truth Surprised Me

Don’t Panic! Follow These Steps If a Bat Gets Into Your House

4 Dangerous Mistakes When Thawing Fish

10 tips to keep thieves away from your home

Mistake #5: Almost everyone makes it—but few actually notice

Tips to Skim Excess Fat from Greasy Soup

Onions Aren’t Just for Cooking: 5 Surprising Hacks

Want to Know If a Shrimp Is Farm-Raised or Wild-Caught?

The secret to removing stubborn stains on glass stovetops without scratching the surface

A Dirt-Cheap Kitchen Item Is the Ultimate Cockroach Kil.ler

7 Mistakes You Should NEVER Make During Hotel Checkout

News Post

A Woman’s Kid.ney Turned to “Stone” and Had to Be Completely Removed

In Autumn, Eat These 3 Lu.ng-Nourishing Dishes Regularly to Prevent Cough and Thr.oat Irritation

3 benefits of old toothbrushes you must know

At 32, Already Suffering from Kid.ney and He.art Failure

The woman gave birth to 2 pairs of twins, although there are already four children in the family

7 Types of Foods That Don’t Spoil Easily

4 Finger Signs That May Signal Li.ver and Lu.ng Can.cer

Japan Reveals the Top 5 Foods to Eat Every Day

Keep the Bathroom Door Open or Closed When Not in Use?

he Leaves of This Plant Are as Precious as the “Ginseng of the Poor,”

Japan Announces 5 Foods to Eat Daily

A bitter taste in your mouth every morning? Don’t take it lightly — it may signal an underlying illness

Miner took his son to the game immediately following work – he had no time to shower

Sudden headache while sweeping the floor, 48-year-old woman went to the doctor and discovered a ruptured brain aneurysm

56-year-old man contracts food poisoning from a favorite dish of many Vietnamese people

Bulging Arm and Hand Veins: Causes and Treatments

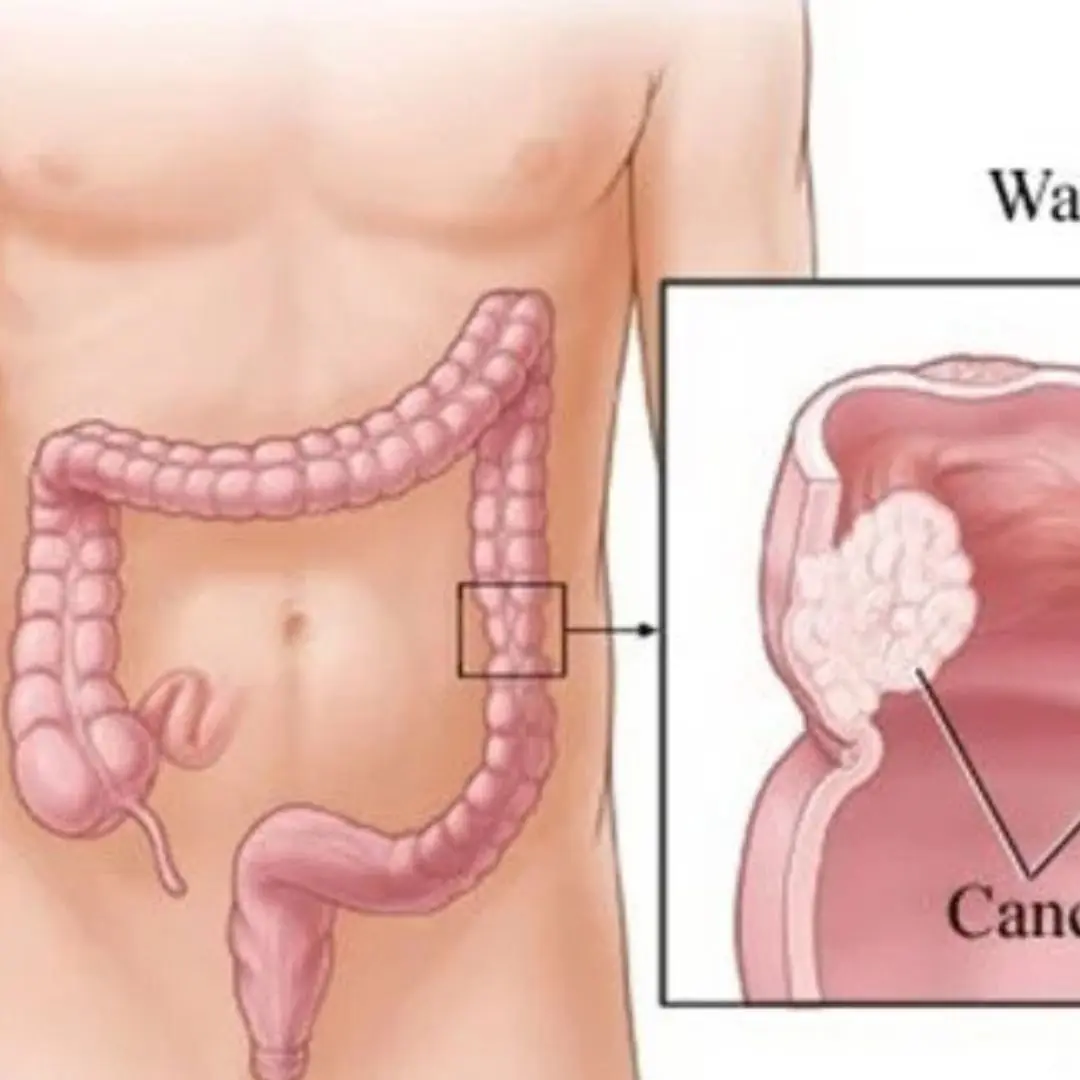

Ca.n.cer is painless at first, but if you notice these 8 signs while going to the bathroom, you should see a doctor immediately

5 Foods That Can Wreck Your Kidn.eys Without Mercy

4 Foods With an Extremely Short Shelf Life After Opening – Don’t Trust the Expiry Date!