He used to sit alone. Now he’s moving closer. Small steps but huge progress for Punch

Not fully inside the circle yet. But no longer outside it either. That’s courage

“The church of St. Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God,” wrote the Anglo-Saxon scholar Alcuin of York, “stripped of all its furnishings, exposed to the plundering of pagans....Who is not afraid at this?” The Vikings are known to have gone on to launch a series of daring raids elsewhere in England, Ireland, and Scotland. They made inroads into France, Spain, and Portugal. They colonized Iceland and Greenland, and even crossed the Atlantic, establishing a settlement in the northern reaches of Newfoundland.

But these were primarily the exploits of Vikings from Norway and Denmark. Less well known are the Vikings of Sweden. Now, the archaeological site of Fröjel on Gotland, a large island in the Baltic Sea around 50 miles east of the Swedish mainland, is helping advance a more nuanced understanding of their activities. While they, too, embarked on ambitious journeys, they came into contact with a very different set of cultures—largely those of Eastern Europe and the Arab world. In addition, these Vikings combined a knack for trading, business, and diplomacy with a willingness to use their own brand of violence to amass great wealth and protect their autonomy.

Gotland today is part of Sweden, but during the Viking Age, roughly 800 to 1150, it was independently ruled. The accumulation of riches on the island from that time is exceptional. More than 700 silver hoards have been found there, and they include around 180,000 coins. By comparison, only 80,000 coins have been found in hoards on all of mainland Sweden, which is more than 100 times as large and had 10 times the population at the time. Just how an island that seemed largely given over to farming and had little in the way of natural resources, aside from sheep and limestone, built up such wealth has been puzzling. Excavations led by archaeologist Dan Carlsson, who runs an annual field school on the island through his cultural heritage management company, Arendus, are beginning to provide some answers.

Traces of around 60 Viking Age coastal settlements have been found on Gotland, says Carlsson. Most were small fishing hamlets with jetties apportioned among nearby farms. Fröjel, which was active from around 600 to 1150, was one of about 10 settlements that grew into small towns, and Carlsson believes that it became a key player in a far-reaching trade network. “Gotlanders were middlemen,” he says, “and they benefited greatly from the exchange of goods from the West to the East, and the other way around.”

Situated between the Swedish mainland and the Baltic states, Gotland was a natural stopping-off point for trading voyages, and Carlsson’s excavations at Fröjel have turned up an abundance of materials that came from afar: antler from mainland Sweden, glass from Italy, amber from Poland or Lithuania, rock crystal from the Caucasus, carnelian from the East, and even a clay egg from the Kiev area thought to symbolize the resurrection of Jesus Christ. And then, of course, there are the coins. Tens of thousands of the silver coins found in hoards on the island came from the Arab world.

Many Gotlanders themselves plied these trade routes. They would sail east to the shores of Eastern Europe and make their way down the great rivers of western Russia, trading and raiding along the way at least as far south as Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, via the Black Sea. Some reports suggest that they also crossed the Caspian Sea and traveled all the way to Baghdad, then the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Entire Viking families are believed to have made their way east. “In the beginning, we thought it was just for trading,” says Carlsson, “but now we see there was a kind of settlement. You find Viking cemeteries far away from the main rivers, in the uplands.” Other evidence of Scandinavian presence in the region is plentiful. As early as the seventh century, there was a Gotlandic settlement at Grobina in Latvia, just inland from the point on the coast closest to Gotland. Large numbers of Scandinavian artifacts have been excavated in northwest Russia, including coin hoards, brooches, and other women’s bronze jewelry. The Rus, the people that gave Russia its name, were made up in part of these Viking transplants. The term’s origins are unclear, but it may have been derived from the Old Norse for “a crew of oarsmen” or a Greek word for “blondes.”

To investigate the links between the Gotland Vikings and the East, Carlsson turned his attention to museum collections and archaeological sites in northwest Russia. “It is fascinating how many artifacts you find in every small museum,” he says. “If they have a museum, they probably have Scandinavian artifacts.” For example, at the museum in Staraya Ladoga, east of St. Petersburg, Carlsson found a large number of Scandinavian items, oval brooches from mainland Sweden, combs, beads, pendants, and objects with runic inscriptions, and even three brooches in the Gotlandic style dating to the seventh and eighth centuries. Scandinavians were initially drawn to the area to obtain furs from local Finns, particularly miniver, the highly desirable white winter coat of the stoat, which they would then trade in Western Europe. As time went on, Staraya Ladoga served as a launching point for Viking forays to the Black and Caspian Seas.

These journeys entailed a good deal of risk. The route south from Kiev toward Constantinople along the Dnieper River was particularly hazardous. A mid-tenth-century document by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus tells of Vikings traveling this stretch each year after the spring thaw, which required portaging around a series of dangerous rapids and fending off attacks by local bandits known as the Pechenegs. The name of one of these rapids—Aifur, meaning “ever-noisy” or “impassable”—appears on a runestone on Gotland dedicated to the memory of a man named Hrafn who died there.

People from the East may have traveled back to Gotland with the Vikings as well. At Fröjel, Carlsson has uncovered two Viking Age cemeteries, one dating from roughly 600 to 900, and the other from 900 to 1000. In all, Carlsson has excavated around 60 burials there, and isotopic analysis has shown that some 15 percent of the people whose graves have been excavated—all buried in the earlier cemetery—came from elsewhere, possibly the East.

In their voyages, the Vikings of Gotland are thought to have traded a broad range of goods such as furs, beeswax, honey, cloth, salt, and iron, which they obtained through a combination of trade and violent theft. This activity, though, doesn’t entirely account for the wealth that archaeologists have uncovered. In recent years, Carlsson and other experts have begun to suspect that a significant portion of their trade may have consisted of a commodity that has left little trace in the archaeological record: slaves. “We still have some problems in explaining what made this island so rich,” says Carlsson. “We know from written Arabic sources that the Rus—the Scandinavians in Russia—were transporting slaves. We just don’t know how big their trading in slaves was.”

According to an early tenth-century account by Ibn Rusta, a Persian geographer, the Rus were nomadic raiders who would set upon Slavic people in their boats and take them captive. They would then transport them to Khazaria or Bulgar, a Silk Road trading hub on the Volga River, where they were offered for sale along with furs. “They sell them for silver coins, which they set in belts and wear around their waists,” writes Ibn Rusta. Another source, Ibn Fadlan, a representative of the Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad who traveled to Bulgar in 921, reports seeing the Rus disembark from their boats with slave girls and sable skins for sale. The Rus warriors, according to his account, would pray to their gods: “I would like you to do me the favor of sending me a merchant who has large quantities of dinars and dirhams [Arab coins] and who will buy everything that I want and not argue with me over my price.” Whenever one of these warriors accumulated 10,000 coins, Ibn Fadlan says, he would melt them down into a neck ring for his wife.

It is unclear whether the Vikings transported Slavic slaves back to Gotland, but the practice of slavery appears to have been well established there. The Guta Lag, a compendium of Gotlandic law thought to have been written down in 1220 includes rules regarding purchasing slaves, or thralls. “The law says that if you buy a man, try him for six days, and if you are not satisfied, bring him back,” says Carlsson. “It sounds like buying an ox or a cow.” Burials belonging to people who came from places other than Gotland are generally situated on the periphery of the graveyards with fewer grave goods, suggesting that they may have occupied a secondary tier of society—perhaps as slaves.

Not fully inside the circle yet. But no longer outside it either. That’s courage

Heart-touching story of a lonely baby monkey in Japan spreads online

Eat Black Beans Every Day and This Is What Could Change

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK

When scholars study the great copper-producing powers of the Mediterranean Bronze Age, they often focus on Cyprus and the Levant.

On the summit of Papoura Mountain in central Crete, archaeologists are investigating a highly unusual circular structure.

he large Neolithic farming community of Çatalhöyük in southern Anatolia has long tantalized archaeologists as a possible example of a matriarchal society.

CHERKASY OBLAST, UKRAINE—SciNews reports that a new study of the bones of small animals recovered from Mezhyrich

Metal and stone tools, faience amulets, and limestone statues are thought to have been made in the other rooms in the building.

Researchers say the findings indicate Syedra was not only a regional producer but one of the Mediterranean’s key suppliers in antiquity, challenging earlier assumptions about the city’s economic role.

The Lydian palace was built on an artificial terrace in the capital city of Sardis.

Statues of gods featured prominently throughout the ancient world, but many of those that are best known from literary evidence have never been found.

Top 10 Discoveries of 2025

As soon as you fit the words “Bible” and “history” into the same sentence, people start reacting.

A tower of silence (known also as a ‘dakhma’) is a type of structure used for funerary purposes by adherents of the Zoroastrian faith.

3 smart and safe approaches to defrost fish quickly without compromising texture

Below are some ways in which your feet might provide early warning signs of heart problems and clogged arteries.

Start your day stronger with eggs and sweet potatoes each morning

Are overnight colon cleanses safe? What experts say

Individuals at higher risk of can.cer may display 3 warning signs in the neck

Unlocking the secret power of Mimosa Pudica: 30 health benefits and DIY applications

Keep these 3 mindsets, and success will follow

The finger you slice first may hint at hidden traits you didn’t notice before

How to respond to a snake bi.te: Critical first steps and the reasons behind them

Why Chayote Squash Is So Good for You: 7 Proven Health Benefits

Not all garlic is safe to buy—learn which cloves you should avoid at the market today.

A simple homemade trap is going viral for eliminating flies, mosquitoes, and bugs in minutes

Waking Up at 3 or 4 A.M.? It Could Be a Clear Sign of an Underlying Issue

Don’t ignore unusual changes in your feet

She Di:ed From a Stroke and Came Back: What She Saw Will Sho:ck You

One mistake nearly cost me my life. Anyone using a heater must know this

Hearing Unusual Sounds in Your Ear? You’re Not Alone

7 Warning Signals Your Body Sends When Stress Is Taking Over

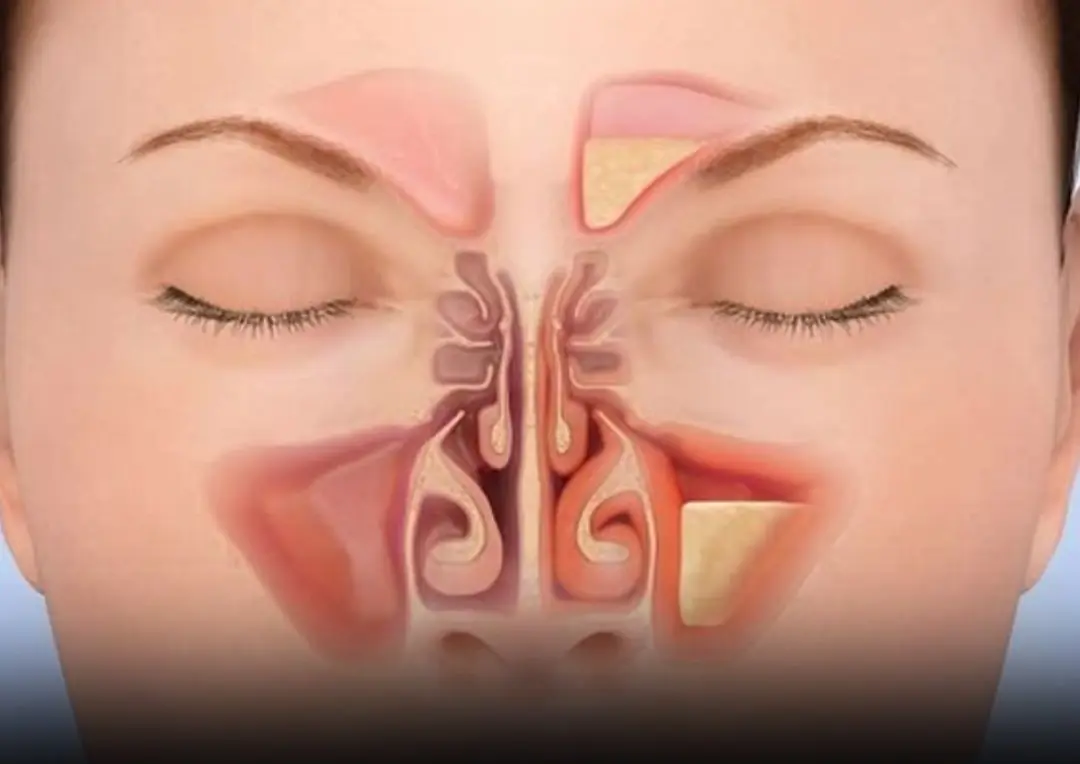

5 Subtle Nose Symptoms That May Point to Underlying Diseases

Some unhealthy habits during intimacy may be a hidden cause of cervical can.cer in women.