Whitmore's 'flesh-eating bac.teria' cases increase: Who is vulnerable?

Whitmore disease, also known as the “flesh-eating bacteria,” has been rising during the rainy season with unpredictable progression. It can cause severe infections and death if not detected early and treated correctly.

Thanh Hoa Children’s Hospital recently saved a 15-year-old boy who suffered from severe lung necrosis and extreme exhaustion after being attacked by the “flesh-eating” bacterium. Upon admission, the patient was in critical condition with persistent high fever, severe fatigue, chest pain, and intense shortness of breath. After emergency care, consultations, and laboratory tests, doctors confirmed infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei—the pathogen that causes Whitmore disease.

In recent years, Whitmore disease—often referred to as the “flesh-eating bacteria”—has drawn increasing attention as case numbers rise again during the rainy season in certain tropical regions.

Although this bacterium has existed for more than a century, it continues to cause misunderstanding and concern, particularly because it can lead to severe infections, tissue necrosis, and a high risk of death if not treated early. Importantly, Whitmore is not transmitted from person to person; instead, it hides in soil, water, and humid environments—elements widely present in daily life.

A tiny but extremely dangerous bacterium

The cause of Whitmore disease is Burkholderia pseudomallei, a bacterium naturally found in soil, mud, and stagnant water. It enters the body through skin abrasions, the respiratory tract, or occasionally the digestive tract. Once inside, it can rapidly spread to multiple organs, causing various types of infections. The bacterium thrives in moisture, especially during the rainy season, increasing infection risk in agricultural areas or flood-prone regions.

The danger of this bacterium does not lie in rapid human-to-human transmission, but in its ability to remain dormant for years and reactivate long after the patient believes they have recovered. This unpredictable nature makes Whitmore a “silent enemy,” especially for people with weakened health or chronic illnesses.

Who is most at risk of Whitmore disease?

Anyone exposed to contaminated soil or water can be infected, but some groups face significantly higher risk:

-

People with diabetes—accounting for a large portion of severe cases and deaths

-

Patients with kidney disease, chronic lung disease, or weakened immune systems

-

Farmers, sanitation workers, and individuals frequently wading in water or mud

-

People with open wounds, especially when soaked in water or exposed to contaminated environments

The worrying aspect is that Whitmore can occur at any age, from children to adults, and in some cases, it progresses very rapidly within just a few days.

Whitmore symptoms are diverse and easily misdiagnosed

Whitmore is known as “the great imitator” because its symptoms are nonspecific and often mistaken for flu, pneumonia, or common skin infections. Patients may experience:

-

Fever, fatigue, muscle pain

-

Pneumonia or persistent cough

-

Skin lesions: unexplained ulcers, swelling, or abscesses

-

Deep abscesses in the liver, lungs, spleen, or multiple organs

-

Septicemia—the most dangerous form, which can lead to shock and sudden death

Whitmore can escalate quickly from mild to life-threatening. Without prompt treatment using the correct antibiotic regimen, it can cause tissue necrosis, severe infection, and fatal outcomes.

Why do people call it “flesh-eating bacteria”?

In reality, Whitmore bacteria do not “eat” human flesh literally. The name comes from severe cases involving tissue necrosis, deep abscesses, or widespread destruction of infected tissues. When patients seek medical care late, these injuries can become extensive, creating the misconception that the bacteria “erode” the body. However, these effects result from severe infection—not a direct chewing mechanism by the bacterium.

The key point is that Whitmore is treatable if detected early and managed with a prolonged antibiotic regimen.

Treatment requires long-term therapy—self-medication is dangerous

Unlike typical infections, Whitmore requires specific antibiotics and a lengthy treatment course lasting 3 to 6 months to prevent relapse. Self-medicating or taking incomplete antibiotic doses can worsen the disease and increase mortality risk.

Treatment includes:

-

Intensive phase: Intravenous antibiotics for 10–14 days or longer in severe cases

-

Eradication phase: Long-term oral antibiotics for several months to eliminate remaining bacteria

Whitmore does not resolve on its own, and there is currently no vaccine available.

How to prevent Whitmore disease effectively?

Prevention depends largely on reducing exposure to contaminated soil and water:

-

Wear shoes, gloves, and boots when working in fields or muddy environments

-

Cover open wounds and avoid exposing broken skin to dirty water

-

Wash hands and shower after work

-

People with chronic illnesses should limit wading in water or working in wet environments

-

Seek medical care early for non-healing wounds, prolonged fever, or signs of infection

In tropical climates—especially during the rainy season—raising awareness about Whitmore is essential to reducing severe cases.

Whitmore is dangerous, but it is not a death sentence if diagnosed and treated properly. What worries specialists most is not the spread of the bacteria, but the tendency of people to ignore symptoms, self-treat, or seek medical care too late.

With climate change, prolonged flooding, and worsening environmental contamination, exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei may increase. Therefore, understanding the disease, preventing exposure, and ensuring timely treatment are the most effective ways to protect health.

News in the same category

Okra is great for your health, but not everyone reacts to it the same way

If You Notice These Two Little Holes on Your Back, It Means You’re Not… Tap to Discover

If You Find This Insect in Your Home, Here’s What It Means

Doctors Reveals That Eating Apples Causes

What are the health consequences of dehydration?

Heartbreaking but Important: Subtle Signs Your Dog May Be Nearing the End of Life

Put a piece of garlic in the middle of the tree, it has great uses, everyone will want to do it

Save a Ton of Electricity Just by Pressing One “Special” Button on Your Washing Machine — Many People Use It for Years Without Knowing

Why Do Flight Attendants Choose to Stay at a Hotel Instead of Going Straight Home After Landing?

Cardiologist answers questions about clip instructing stroke check with finger that has millions of views on social networks

Many people think it's for decoration!

What it says about your relationship when your partner sleeps with their back to you

If you hear ringing in your ear, this is a sign that you will suffer from...

When a cat rubs against you, this is what it means

Why do dogs often chase strangers

5 bad habits that increase the risk of str.oke at night

The Silent Mystery of Seat 11A: From the Most Hated Spot to a “Lucky Charm” That Saved the Only Survivors of Two Air Disasters

News Post

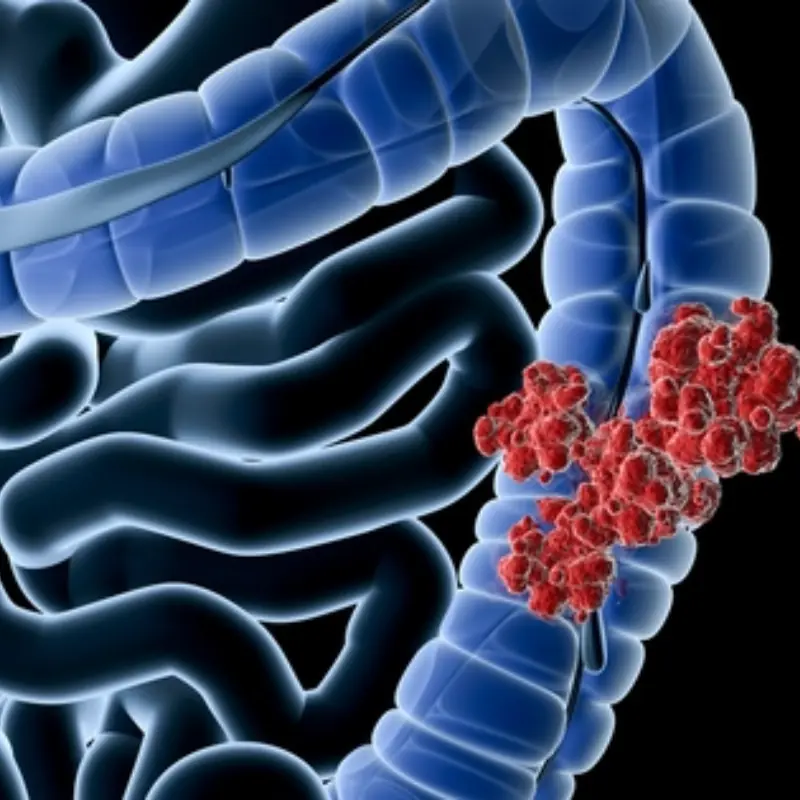

To Prevent Colon Can.cer, This Is the First Thing You Need to Do

Shrimp & Pork Ball Bowl with Shimeji Mushrooms

Heart Surgeon Reveals: Eating Eggs Every Day May Help You Live Longer

The Surprising Benefits of Eating Boiled Sweet Potatoes for Breakfast: How Your Body Can Change Over Time

29-year-old girl hospitalized for bleeding duodenal ulcer: Doctor warns of 2 harmful habits

Hair loss: Doctor points out 3 mistakes when washing and drying hair and 4 ways to fix them

The truth about hotel mirrors, check now to ensure safety

To clean pig intestines, you only need to use one cheap thing, clean quickly, and have no fishy smell

5 groups of people advised not to consume bread

Reasons why you shouldn't open your bedroom door at night

DANGEROUS COMPLICATIONS OF PULPITIS

Butter Steak Bites with Mashed Potatoes & Glazed Carrots – A Comfort Plate With Serious Flavor

What causes black thorn disease?

Baked Sweet Potatoes with Garlic Butter.

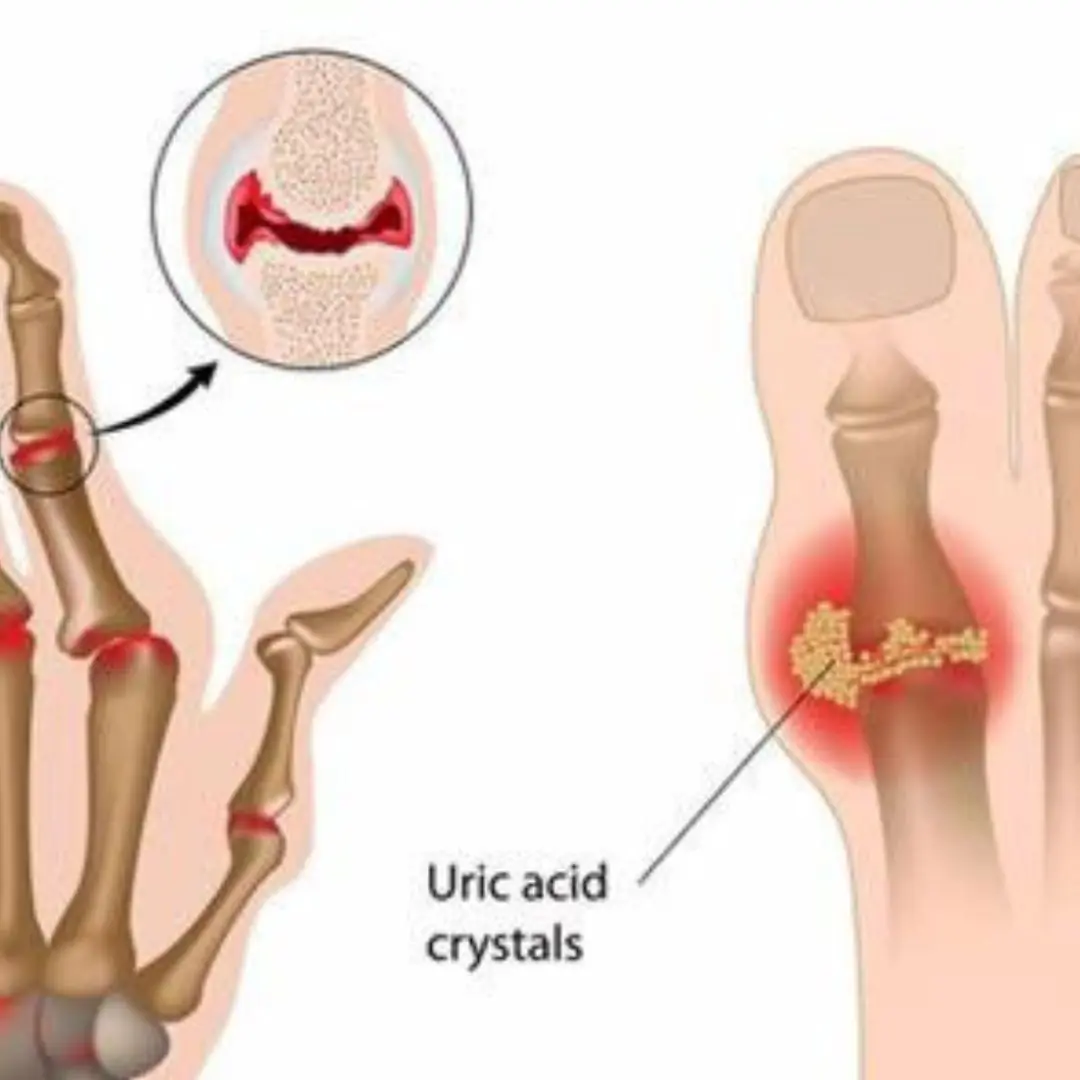

The #1 Drink to Reverse High Uric Acid and Gout — Backed by Science

If You Wake Up With These 4 Morning Symptoms, Sorry — Your Kid.neys May Be in Trouble

Drinking Coffee at the Wrong Time May Harm Your Heart:

Cardiologist reveals 3 drinks that help control blo.od pressure

A single ingredient to combat bone pain, diabetes, anxiety, depression, and constipation